An extremely rare, completely articulated dinosaur embryo was discovered inside a fossilized egg that had been accumulating dust in a museum storage space in China for more than ten years. The fetal specimen, estimated to be between 66 and 72 million years old, indicates a remarkable connection between dinosaurs and contemporary birds.

The unhatched species, an oviraptorosaur, is thought to be around 27 centimeters (10.6 inches) long and is the first instance of a dinosaur embryo exhibiting a position similar to modern bird embryos. Oviraptorosaurs are a group of feathered, toothless theropods. Modern birds perform a sequence of tucking motions just before hatching that entail bending their bodies and putting their heads beneath their wings, but the evolutionary roots of this behavior were unclear until recently.

The Baby Yingliang specimen’s head was discovered ventral to the body, with the feet on each side, and the back coiled around the blunt pole of the egg, according to the study’s authors, who report their discovery in the journal iScience. Previously unknown in a non-avian dinosaur, they claim that this stance is “reminiscent of a late-stage contemporary bird embryo.”

Birds are believed to tuck throughout the hatching process, and those who do not do so are significantly less likely to survive their departure from the egg. The fact that Baby Yingliang appears to have adopted the same position raises the possibility that the phenomena originated with the theropod ancestors of current birds.

In response to this exciting finding, research author Professor Steve Brusatte said, “This small pregnant dinosaur looks precisely like a young bird wrapped in its egg, which is still more proof that many traits characteristic of today’s birds initially originated in their dinosaur relatives.”

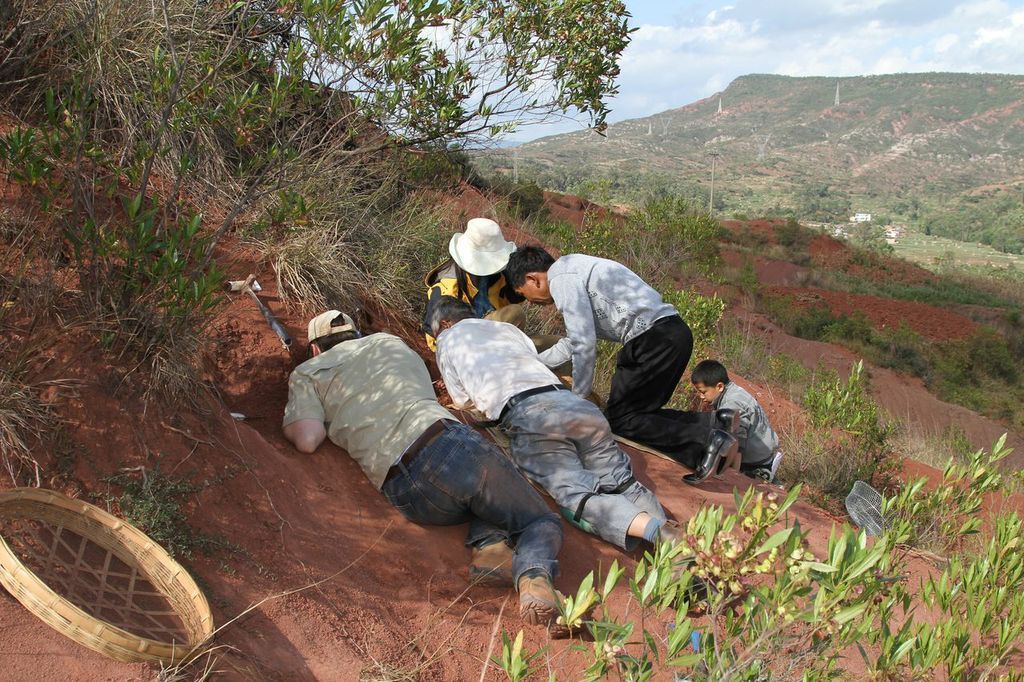

Baby Yingliang, which is kept in the Yingliang Stone Nature History Museum, is one of the most complete dinosaur embryos ever discovered, giving scientists a unique opportunity to study an unharmed young theropod. The authors of the study acknowledge that no definite conclusions about the nature of dinosaur embryos can be taken from their observations because this fossil is the sole one of its kind; further research will be required before any ideas can be validated.

However, they come at the following conclusion: “This new remarkable fossil embryo implies that several early developmental characteristics (tucking) generally assumed to be exclusively avian may be anchored more deeply in the theropod lineage.”

Amazing!

Sure. Dinosaurs. Are. Real. So. Is. Good. God. Above. He. Made. Mee. He. Made. You. True. Blue. And. Beautiful!!

Awesome…..and very interesting!!

It looks amazing, but it’s an artist’s reconstruction. What the paleontologists saw was a clump of fossilized bones..