The earliest genetic data discovered to date came from a horse discovered preserved in Canadian permafrost 780–560 thousand years ago. Everything has changed now.

An multinational team lead by scientists from Stockholm’s Centre for Palaeogenetics sequenced DNA obtained from the bones of three ancient mammoths, one of which had been buried for more than 1.2 million years in Siberian permafrost. The researchers were able to disprove the old theory that the iconic Columbian mammoth originated before the smaller, shaggier woolly mammoth by examining the DNA, revealing a new mammoth lineage. The research was published in the journal Nature.

Two of the three mammoths are over a million years old and predate the woolly mammoth, while the third is roughly 700,000 years old and is one of the earliest known woolly mammoths (Mammuthus primigenius). Their teeth were used to collect the genetic material.

“By a long shot, this is the oldest DNA ever recovered,” said research author Professor Love Dalén of Stockholm’s Centre for Palaeogenetics.

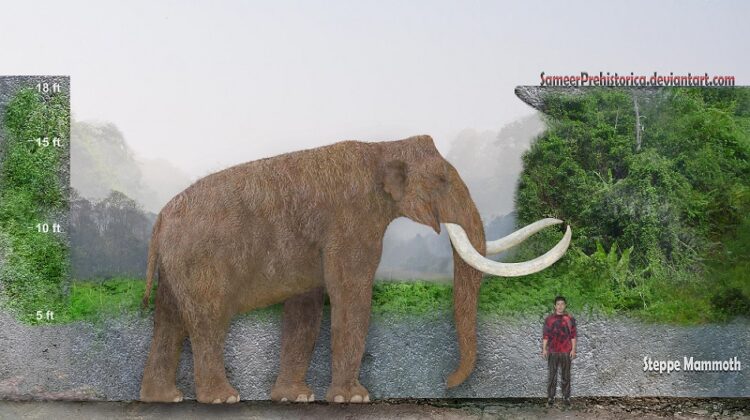

An ancient steppe mammoth (Mammuthus trogontherii), a direct progenitor of the woolly mammoth and possibly the biggest mammoth species and proboscidean, is the second oldest specimen. The giant steppe mammoth was up to 15 feet tall and weighed between 12 and 14 tons. It is one of the world’s biggest terrestrial animals.

Even more intriguing, the scientists discovered that the oldest specimen tested belonged to a previously undiscovered mammoth genetic branch known as the Krestovka mammoth. Scientists believe it to be 1.2 million years old, based on the age of the geological region where it was discovered. However, mitochondrial genome evidence suggests that this specimen might be as ancient as 1.65 million years, while the second (steppe) mammoth could be as old as 1.34 million years.

The Columbian mammoth (Mammuthus columbi) that lived in North America during the last ice age was a mix of the woolly mammoth and a previously unknown mammoth genetic ancestry, according to the findings.

However, getting those results wasn’t simple for the scientists involved, as the DNA of these archaic creatures has seen better days, to put it lightly. In fact, over millennia, it has deteriorated to the point that, instead of a lovely long strip of immaculate genetic material, the study team was presented with billions of weird, microscopic bits of DNA, which they had to methodically piece together, much like a jigsaw.

“We have a lot of little jigsaw pieces and are attempting to put the puzzle together.” The smaller the piece, the more difficult it is to put the puzzle back together,” said Dr. Tom van der Valk, the study’s principal author.

With a little dentist’s drill, the researchers began by removing a small amount of material from the inside of each mammoth tooth. The DNA was then isolated from the resultant tooth powder using chemicals and enzymes, followed by a washing procedure.

The majority of the retrieved DNA was made up of small sequences of a few hundreds of base pairs. (In double-stranded nucleic acids, a base pair is a fundamental unit that contributes to the folded structure of both DNA and RNA.)

To make matters worse, many of the jigsaw pieces they found belonged to germs or fungus that had contaminated the material, not the mammoths. Fortunately, the researchers possessed high-quality genomes of woolly mammoths and modern elephant cousins to look to.

In Siberia’s melting permafrost, researchers are looking for ancient genes.

After removing all non-mammoth DNA, the researchers were left with between 49 million and 3.7 billion base pairs in each of their three samples. (With 3.2 billion base pairs, the mammoth DNA is somewhat bigger than the human genome.) The researchers then matched their findings to elephant DNA for a second time, allowing them to correctly organize all of the recoverable DNA pieces.

With the latest findings, the researchers believe it is theoretically conceivable to retrieve DNA much older than that found in these mammoths. However, because no permafrost in the Northern Hemisphere is older than 2.5 million years, the researchers cautioned that retrieving DNA from permafrost older than that might be challenging, if not impossible. Of fact, even this “restricted” timeline holds a lot of potential for discovery, especially as new information emerges.

Professor Dalén said, “It’s highly feasible that in the future, procedures may be available to retrieve DNA from human non-permafrost specimens that are close to 1 million years old.”

“Another option is to look for a Homo Erectus in the permafrost.” Although no such discovery have been made to yet, it’s likely that human remains will be discovered in this age’s permafrost. In that situation, obtaining genomic DNA from these [hominin specimens] would be more or less as simple as obtaining DNA from mammoths.”

We’re excited to watch and report on the outcomes of that new search for scientific knowledge, if it ever takes place.