The biggest known insect species to have ever existed on Earth is a gigantic example of the extinct dragonfly-like group of griffinflies.

The atlas moth (which has the largest wings by surface area at 160 cm2 or 25 in2), the white witch moth (which has the greatest wingspan at about 30 cm or 12 in), and the goliath beetle (which is the heaviest insect at 115 g) are the three largest living insect species we know today (4.1 oz).

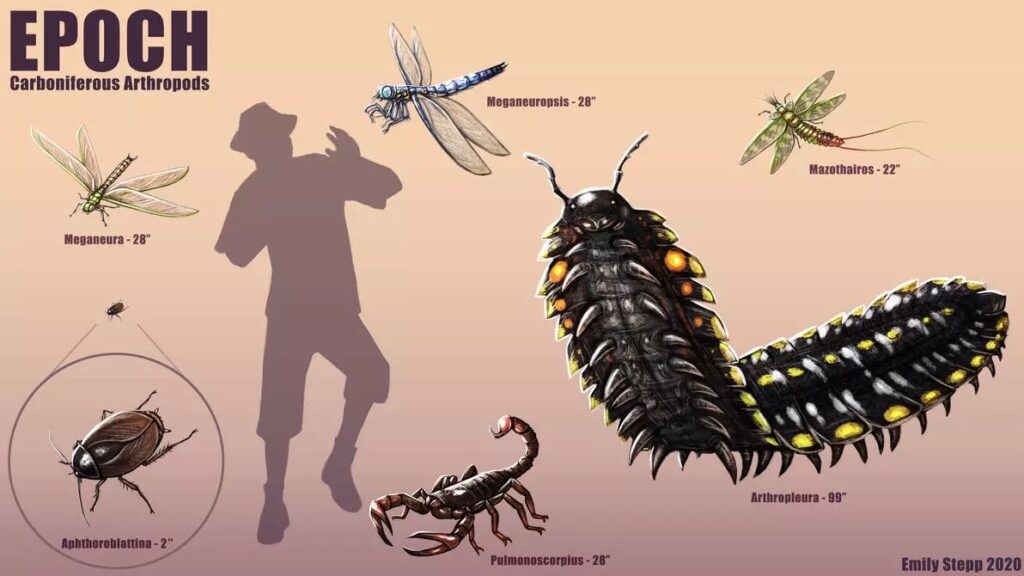

Insects’ progenitors, like those of most other animal taxa, were generally larger than their modern equivalents. Giant griffinflies like Meganeura monyi and Meganeuropsis permiana are among them, and they are the world’s biggest known insect species. The atlas moth has a wingspan of 75 cm (28 in), which is almost three times that of these species. Their maximum body mass is unknown, although estimates range from 34 g to 240 g, implying that they can grow to be more than twice the size of the goliath beetle.

When you walk on a cockroach, you’ll hear a crunchy sound that some people enjoy and others despise. Squeezing and shattering of the exoskeleton, which is extremely hard in cockroaches, produces it. The exoskeleton of other insects, on the other hand, is not necessarily as rigid, and various regions of the body may have variable degrees of firmness.

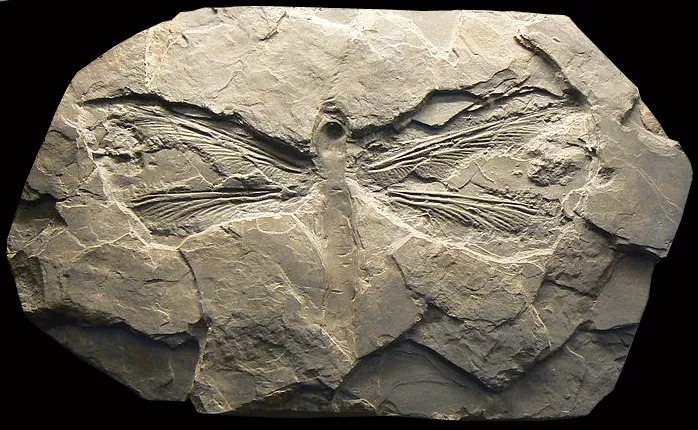

The wings, on the other hand, are the most robust body components of griffinflies, and hence the portions that are most likely to be fossilized. With a few notable exceptions, the majority of griffinfly fossil records are fragmented specimens.

During the Late Carboniferous and Late Permian eras circa 317-247 million years ago, griffinflies sailed the skies of our globe for almost 20 million years, establishing a global distribution. Their genus was fairly varied, with scientists routinely describing new species. However, not all of them were enormous; some were smaller than current dragonflies. Others, on the other hand, were enormous even by dragonfly standards.

Meganeura monyi was the first griffinfly to be described, and it was based on a single 12 inch long fossil wing. It was the biggest insect known at the time of its description in 1895, with an estimated wingspan of roughly 27 inches (68,5 cm). Frank Carpenter, on the other hand, described Meganeuropsis permiana in 1939, based on a partial but massive wing found in two sections. Carpenter estimated the newly discovered species’ wingspan to be 29 inches (almost 75 cm). He described Meganeuropsis americana, a new species of griffenfly with a wingspan identical to M. permiana, a few years later. Today, experts believe the two Meganeuopsis species to be the same and refer to them as M. permiana.

This species holds the distinction for being the biggest insect ever known to exist.

But, in today’s world, why aren’t there any such massive dragonflies? What was it that permitted griffinflies to grow so large?

The Late Paleozoic epoch of Earth’s history was unique in several ways. Extensive coal swamp forests flourished throughout the Late Carboniferous and Early Permian periods, producing massive quantities of oxygen as a consequence of photosynthesis. This resulted in a hyperoxic environment, with oxygen levels much above current levels.

Insects breathe through a set of tubes (trachea) that are linked to the outside since they lack lungs. By simple diffusion, oxygen is absorbed through the tubes’ walls. Insects absorbed more oxygen when atmospheric oxygen levels increased, allowing them to acquire massive body sizes. The anatomy of griffinflies suggests that they have extremely agile flying skills that are metabolically demanding and require a lot of oxygen.

However, throughout the Permian epoch, oxygen levels began to decline, which was accompanied by an increase in aridity. This might have eventually resulted in the extinction of these enormous insects. Similar gigantism in active airborne predatory insects would be impossible due to today’s low oxygen levels in the atmosphere.

During the lengthy time when griffinflies lived, they were the masters of the air. Bats, birds, and pterosaurs were not expected to emerge for another 100 million years, so the sky were devoid of even more active fliers that could have preyed on them.

Of course, this has aided their lengthy survival as well as, according to certain views, their bodily size.