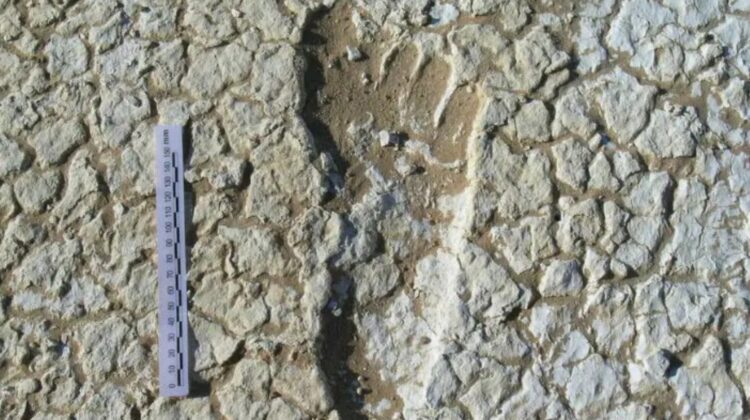

The discovery of 20,000-year-old human footprints in Australia has revealed fascinating insights into the lives of the country’s early Aboriginal ancestors. These fossil footprints, which include a set of 23 tracks containing 400 prints, were discovered in 2003 in Mungo National Park, located 195 miles from Broken Hill.

Biological archaeologist Steve Webb from Bond University in Queensland has been studying and partially excavating the tracks with the help of other scientists and members of three area Aboriginal tribes. Last December, Webb published a study in the Journal of Human Evolution describing eight of the tracks, with his work continuing to uncover more information.

The footprints reveal things that archaeological sites or skeletal remains couldn’t, according to Webb. For example, they suggest that the Aboriginal ancestors were very active in the area, despite previous assumptions that they were nomadic. Additionally, the footprints demonstrate that these people were tall, in good health, and very athletic. One hunter was even running at 23 miles (37 kilometers) an hour, or as fast as an Olympic sprinter.

The footprints have also held puzzles, such as the tracks of what experts say was a one-legged man. “All we could pick up was the right foot,” Webb said, adding that each step left a deep impression in the mud. However, with the help of five trackers from the Pintubi people of central Australia, the conundrum was solved. “They looked at the track and said, ‘Yes, it’s definitely a one-legged man’,” Webb said. The trackers believed the ancient man probably threw his support stick away and hopped quite fast on one foot.

The discovery of these footprints highlights just how clever and adaptable the Aboriginal ancestors were, according to Mary Pappen, Sr., a Mutthi Mutthi tribal elder. “We did not die 60,000 years ago. We didn’t dry up and die away 26,000 years ago when the lakes were last full,” she said. “We are a people that nurtured and looked after our landscape and walked across it, and we are still here today.”

For now, the excavated tracks sit under protective layers of cloth and dirt to shelter them from erosion caused by wind, sand, and rain. The footprints will stay there until scientists and Aboriginal community members devise a plan to protect the ancient tracks. As part of the plan, tribespeople want to erect community and educational centers near the site and develop related ecotourism. They also hope to build a “keeping place,” or sacred shelter, to safeguard the footprints of their ancestral families.

Leave a Reply