One of the world’s most important wildlife corridors is emerging from the fragmented forests of coastal Brazil after a decade of hard work.

Sometimes conserving rare species and habitats necessitates waiting a few years for all of the puzzle pieces to fall into place.

That process took more than a decade for one project on the coast of Brazil. But, after years of hard work, the puzzle is nearly finished, and what could become one of the world’s most important wildlife corridors is about to emerge.

The Fazenda Dourada corridor in Rio de Janeiro will connect two isolated federal biological reserves — Unio and Poço das Antes — with newly restored forests and a bridge over a major highway, creating a migratory pathway for the endangered golden lion tamarin (Leontopithecus rosalia) and potentially thousands of other endangered species to travel through previously degraded and fragmented landscapes.

The project is a collaboration between Brazil’s Associaço Mico-Leo-Dourado (Golden Lion Tamarin Association) and the non-profit SavingSpecies in the United States. It was made possible by a grant from the Dutch foundation DOB Ecology.

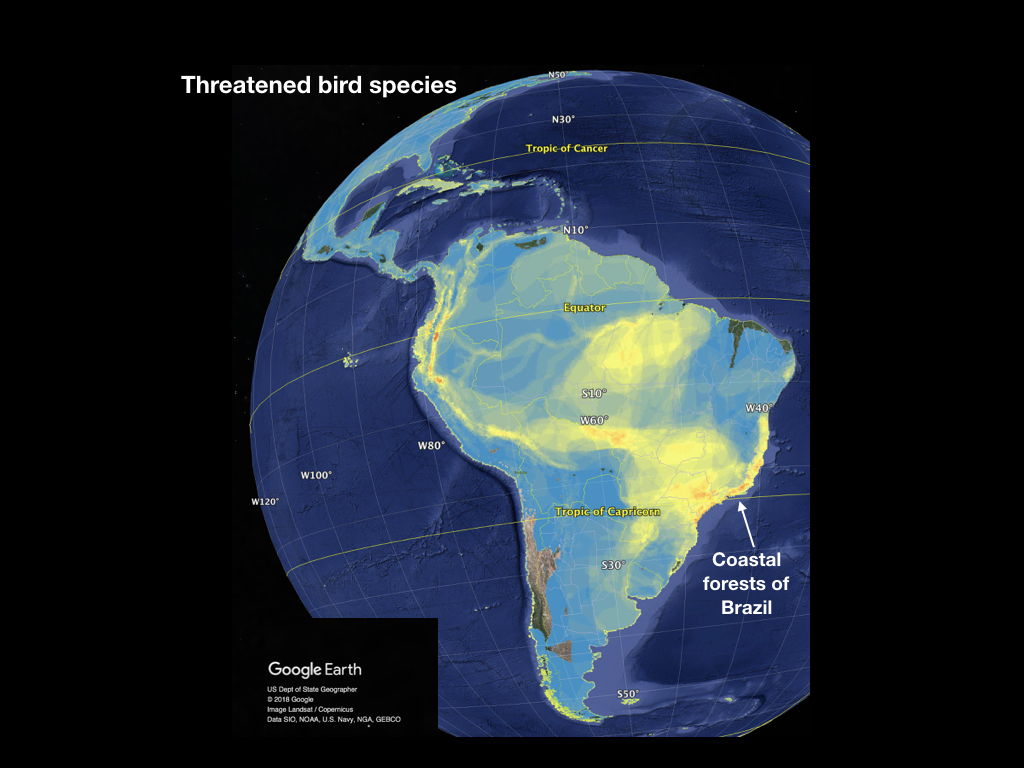

According to Stuart Pimm, Doris Duke chair of conservation at Duke University and president of SavingSpecies, the iconic golden lion tamarin served as the flagship species for this restoration “because it’s such a charismatic animal.” The species was nearly extinct 30 years ago, and the corridor will be critical to their continued recovery; however, the location will also benefit many other rare species. “Coastal Brazil probably has more endangered species than anywhere else in the Americas,” he claims. “It certainly has more endangered birds, but it’s also a major center for endemic mammals and amphibians, as well as approximately 6,000 plant species.”

The biodiversity-rich region has also experienced “just appalling levels of habitat loss,” according to Pimm. It’s a very disjointed landscape. The habitat that has survived is in shambles.” Many of the species found in this region have very small ranges, putting them at risk of extinction if their habitats are destroyed or populations become separated from one another, he says.

For the past ten years, the two nonprofits have collaborated to acquire land and then restore approximately 50 miles of forest between the two federal reserves. “We’ve planted over 30 tree species,” Pimm says, noting that Associaço Mico-Leo-Dourado has done the majority of the hard work on the ground. “I only planted two trees, but they planted thousands.”

Of course, restoring habitats takes time, but Pimm, 69, is pleased with how quickly the forests have begun to recover. “I thought I’d be dead before it did anything, but the incredible thing is that this is a tropical forest.” It’s warm and wet, and once trees are allowed to grow, they grow quickly.” Some of the trees, he claims, have already grown to 30 feet in height, and the efforts are bearing fruit. “You can look at Google Earth satellite imagery to see how it’s all coming back.”

The final piece of the puzzle took the longest to put together. Last month, the two organizations announced the purchase of a 585-acre plot of land near a major highway north of Poço das Antas. Approximately half of the land, which is currently used for pasture, will be reforested. At the same time, a bridge across the highway will be built, allowing wildlife in the two reserves to reconnect and expand their habitats.

“I knew the challenge would be connecting these populations across the highway,” Pimm says. “We needed two miracles, not one.” We needed to convince the road company to build this habitat bridge so that the species could cross the road, which they agreed to do, and then we needed to acquire more land on the other side of the road. We received the funds about a year and a half ago. It took that long to reach an agreement with the property owner, but now we have the opportunity to create this truly exceptional wildlife corridor.”

According to the two organizations, this is about more than just helping wildlife, such as the iconic tamarin; it is also about repairing the “tear” in the Brazilian rainforest. “This is an especially important step toward our vision of connecting and protecting enough forest to support a viable population of golden lion tamarins for the foreseeable future,” Associaço Mico-Leo-Dourado executive director Lus Paulo Ferraz said in a press release. “Because forest fragmentation from development and linear infrastructure is a constant threat, restoring and protecting the Atlantic Forest is the only way for its magnificent biodiversity to survive.”

Pimm goes on to say that this corridor, as well as the decade of forest-restoration efforts associated with it, demonstrate that the puzzle pieces of hard work, determination, and a little bit of time can pay off — and possibly change the fate of the world’s most endangered species. “This is an example of us attacking,” he says. “We don’t have to accept that bad things happen.” Landscapes will be reconnected. We can use smart, informed science to start reversing the declines. We can finally begin to reclaim nature.”

Leave a Reply