Mice on the rainy side of the Andes grow much bigger than those in on the drier side, and the difference may reveal a previously unnoticed law of nature.

Carl Bergmann discovered that animals in higher latitudes are larger than those in equatorial regions. “What about very tropical elephants and hippopotami?” you might ask, but Bergmann was thinking about differences within species, not differences between them. We now know why nearly two centuries of research has confirmed what is now known as Bermann’s Rule. Smaller animals have more surface area to body mass, which means they lose energy faster, which is advantageous in hot climates but disadvantageous in cold climates.

Dr. Noé de la Sancha of the Field Museum and colleagues believe they have developed a new version that applies to rainfall rather than temperature, which they have published in the Journal of Biogeography.

“There are a number of ecogeographic rules that scientists use to explain trends that we see in nature over and over,” de la Sancha said in a statement. “I believe we have discovered a new one with this paper: the rain shadow effect can cause changes in size and shape in mammals.”

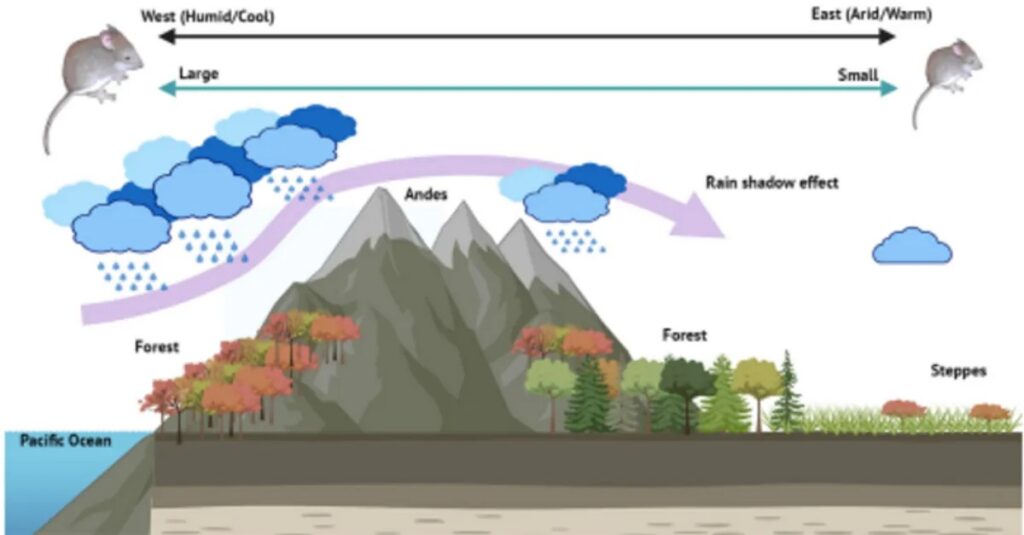

Rain shadows form when winds blow consistently from one direction over mountains, picking up a lot of water vapour from oceans or rainforests. Mountains push clouds upwards into colder air, causing them to dump the majority of the water they carry. There is very little water vapour left after passing over the mountains. As a result, the windward side of the mountains can be extremely wet, while the opposite side is dry.

This is such a common geographical feature that it is often taught in high school, but the impact on the people who live on the slopes is much less understood.

Dr. Pablo Teta of the Museo Argentino de Ciencias Naturales was not looking to discover a broad biogeographic principle; he was simply looking into some overlooked mice. “They’re very cute little buggers, with soft white bellies,” said de la Sancha. “They live in the mountains, which distinguishes them, but they can also be found at lower elevations.” Overall, they haven’t been thoroughly researched.”

Teta noticed an unusual spread in the sizes of 450 mouse skulls, but mitochondrial DNA suggested that multiple species were unlikely. Bergmann’s rule had only a minor effect on size despite being collected over 19 degrees of latitude. The authors attempted to investigate a variety of other variables derived from the locations where the skulls were collected, the most important of which was longitude.

While teaching an ecology class about the rain shadow effect, de la Sancha remembered the Andes as a particularly clear example, and discovered the larger mice were on the rainy side. “The difference is extreme on some mountains.” “One side could be a tropical rainforest, and the other almost desert-like,” de la Sancha explained.

Further investigation revealed that his suspicion was based on the “resource rule,” which states that members of a species grow larger where food and other resources are abundant. More rain means more plant life on the west side of the mountains, which means bigger mice. This may seem obvious, but according to de la Sancha, no one has ever discovered a link between rain shadows and mammal size before.

If the mice are the only species with this effect, the team will have discovered a curiosity, but if further research reveals a pattern, this could one day be considered a rule on par with Bergmann’s. After all, “mountains cover approximately 22% of the planet’s terrestrial surface,” so there is a lot of potentially affected territory, according to the paper.

However, all geography now exists in a different shadow: that of climate change. Nobody knows what the future holds for the cute mice, but rain patterns are changing, and the mice may suffer as a result. This is in addition to the universal alpine threat of rising temperatures forcing people higher up slopes. “At some point, you run out of mountain,” de la Sancha explained.

The Andes are high enough to give the mice enough space, but without more research, we won’t know if they’re another threatened species.

Leave a Reply