A ‘mortsafe’ was an 18th Century invention designed to protect graves from disturbance.

British authorities, turning a blind eye to grave-robbing, allowed surgeons and students to advance medical knowledge through illicit means. They deliberately minimized publicity to keep the public unaware of these activities. When grave-robbing was exposed, it often led to riots, property damage, and even fatal assaults.

As the number of medical schools and students surged in the early 19th century, grave-robbing became rampant in secluded graveyards and urban burial grounds. Corpses were stolen and transported, sometimes across oceans, for sale to medical institutions. Public outrage was particularly intense in Scotland, where deep reverence for the dead and a literal interpretation of the Resurrection prevailed. It was believed that incomplete bodies could not be resurrected, prompting strong efforts to protect burial sites.

Wealthy families could afford robust table tombstones, vaults, mausoleums, and iron enclosures around graves. Those with fewer means placed flowers and pebbles atop graves to signal disturbances and fortified soil with heather and branches to hinder exhumation efforts. Large stones, sometimes shaped like coffins, were placed over fresh graves, often donated by affluent patrons. Friends and family took shifts or hired guards to watch over graves during the night.

In some cases, watch-houses were constructed, like the three-story fortified structure with windows in Edinburgh. Communities formed watch societies, such as the 2,000-member group in Glasgow. Despite these precautions, grave violations still occurred, even with watch-houses in place.

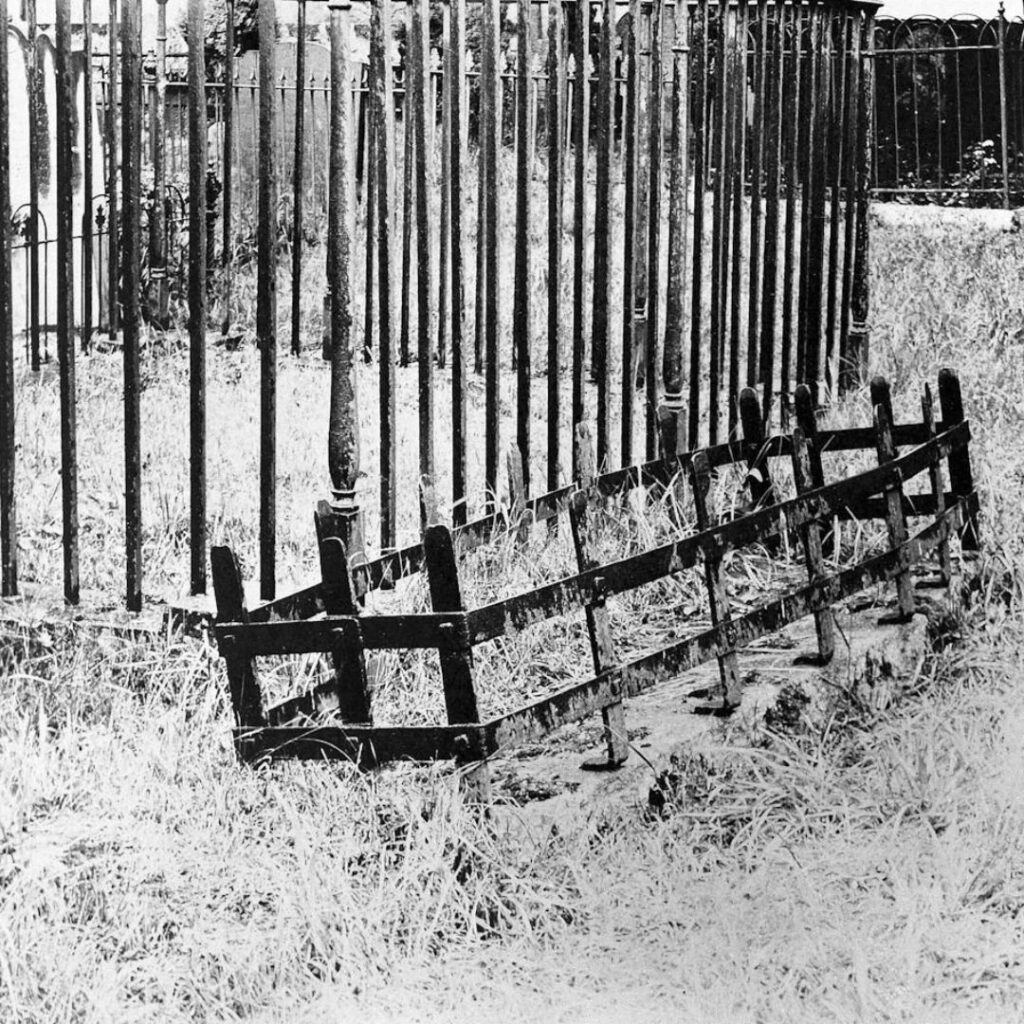

The mortsafe, invented around 1816, came in various designs, primarily made of iron or a combination of iron and stone. These heavy and intricate devices featured interlocked rods and plates secured with padlocks. A typical mortsafe had a plate placed over the coffin, with rods inserted through holes and secured by a second plate. Removal required two individuals with keys and was done after six weeks, once the body had decomposed sufficiently. A model of this mortsafe type is displayed in the Marischal Museum in Aberdeen.

Churches occasionally purchased and rented out mortsafes, and societies were established to regulate their use, requiring annual membership fees and charging non-members.

The crimes committed by Burke and Hare deepened public dread, leading to the erection of vaults in Scotland. These repositories for deceased bodies, funded publicly, were subject to specific rules and regulations. Some vaults were above ground, while others, especially in Aberdeenshire, were partially or entirely subterranean.

In Udny Green, Aberdeenshire, the morthouse features a robust wooden door and an inner iron door, with a turntable that rotated coffins to make bodies unsuitable for dissection by the time they completed their rotation.

Today, surviving mortsafes are found mainly in churchyards and burial grounds, though many are deteriorating. One has been refurbished and is displayed in a church porch by the East Lothian Antiquary Society. A few are housed in museums but often lack information about their purpose. Well-preserved examples include those outside the old Aberfoyle church in Stirling and Skene Parish Church in Aberdeenshire, as well as a mortsafe in the kirkyard of Towie.

Leave a Reply