There has never been more of their DNA on Earth.

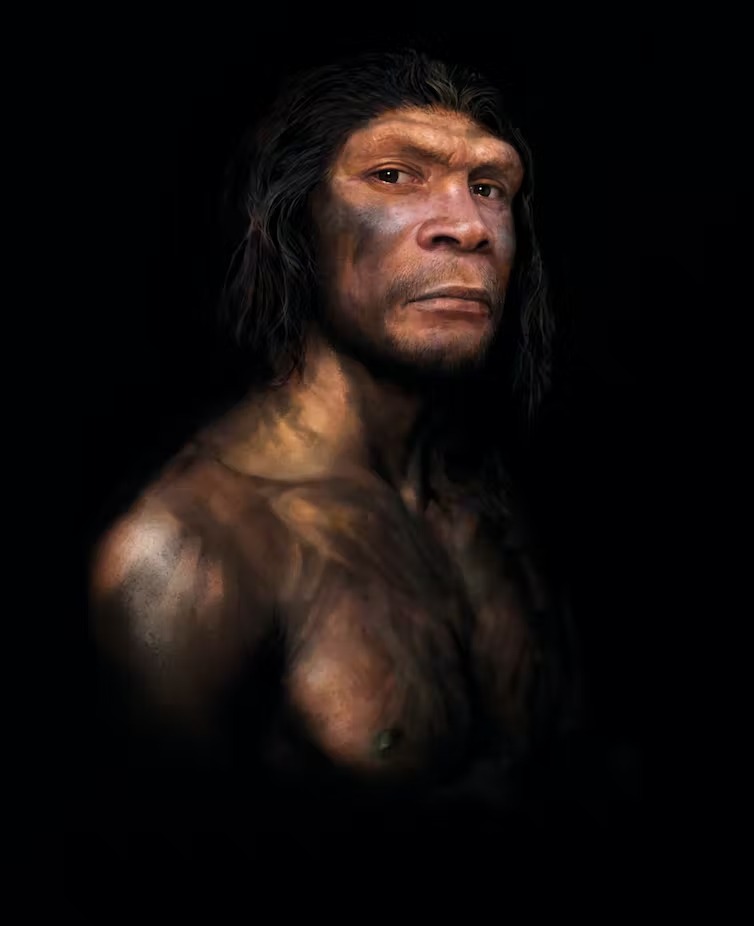

Since their discovery in 1856, Neanderthals have acted as a mirror of our own humanity. What we believe we know about them has been fashioned and molded to conform to cultural trends, societal conventions, and scientific standards. From ill specimens to primordial sub-human lumbering relatives to sophisticated humans, they have evolved.

We now know that Homo neanderthalensis was remarkably similar to us, and that we even met and interbred with them. But why did they become extinct while humans lived, thrived, and eventually took over the world?

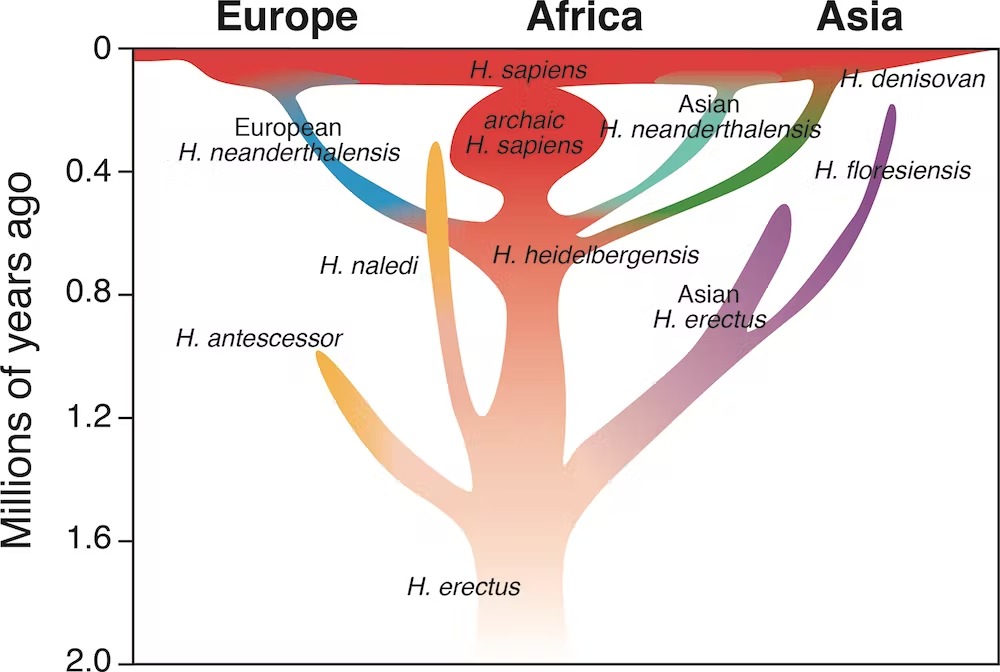

Neanderthals descended from an older progenitor, Homo heidelbergensis, around 400,000 years ago. They were immensely popular and spread from the Mediterranean to Siberia. They were very clever, having brains that were on average larger than those of Homo sapiens.

They hunted large animals, harvested herbs, mushrooms, and shellfish, regulated fire to cook, constructed composite tools, manufactured garments out of animal skins, made beads out of shells, and carved symbols on cave walls. They looked after their children, the elderly, and the feeble, built shelters for protection, endured severe winters and hot summers, and buried their dead.

Neanderthals did come into contact with our ancestors on multiple times over tens of thousands of years, and the two species shared the European continent for at least 14,000 years. They even had a relationship.

Death of a species

The biggest major distinction between Neanderthals and ourselves is that they were extinct around 40,000 years ago. The specific reason of their extinction remains unknown, but we believe it was the consequence of a mix of events.

First, the temperature during the last ice age was very varied, moving from cold to warm and back again, putting a strain on animal and plant food supplies and requiring Neanderthals to continually adjust to environmental change. Second, there were never that many Neanderthals, with the whole population never numbering more than tens of thousands.

They lived in groups of five to fifteen people, as opposed to Homo Sapiens, who lived in groups of up to 150 people. These tiny, isolated Neanderthal groups may have become genetically unsustainable over time.

Third, there was competition from other predators, including groups of modern humans that came from Africa some 60,000 years ago. We believe that many Neanderthals were incorporated into bigger groupings of Homo sapiens.

Where’s the evidence?

Neanderthals left various traces for us to investigate tens of thousands of years later, much of which may be viewed at the Natural History Museum of Denmark’s special exhibition, which we helped arrange. We’ve recovered fossil bones, stone and wooden tools, trinkets and jewelry they left behind, discovered cemeteries, and now we’ve sequenced their genome using ancient DNA. The DNA of Neanderthals and contemporary humans appears to be 99.7% similar, meaning they are our closest extinct ancestors.

The evidence of interbreeding that has left traces of DNA in live humans was perhaps the most shocking finding. Many Europeans and Asians contain 1% to 4% Neanderthal DNA, but Africans south of the Sahara have nearly none. With a current global population of almost 8 billion people, this indicates that there has never been more Neanderthal DNA on the planet.

The Neanderthal DNA also helps us learn more about their appearance, as evidence suggests that certain Neanderthals evolved pale complexion and red hair long before Homo sapiens. The numerous genes shared by Neanderthals and contemporary humans are associated with anything from the ability to taste bitter foods to the ability to talk.

We have also gained a better understanding of human health. Some Neanderthal DNA, for example, that may have been advantageous to humans tens of thousands of years ago today appears to create problems when mixed with a modern western lifestyle.

Alcoholism, obesity, allergies, blood clotting, and depression have all been linked. Recently, scientists proposed that an ancient gene mutation from Neanderthals may raise the likelihood of significant consequences from COVID-19 infection.

Holding up a mirror

The Neanderthals, like the dinosaurs, had no idea what was in store for them. The dinosaurs, on the other hand, vanished abruptly after being struck by a massive meteorite from space. The extinction of the Neanderthals occurred gradually. They finally lost their planet, a cozy house they had successfully occupied for hundreds of thousands of years that gradually turned against them, until life itself became untenable.

Neanderthals now serve a distinct role in that regard. We see ourselves in them. They had no idea what was happening to them and had no option but to continue on the path that would eventually lead to extinction. We, on the other hand, are acutely aware of our predicament and the influence we have on the globe.

Human activity is altering the climate and accelerating the sixth mass extinction. We can reflect on the mess we’ve created and take action to correct it.

If we don’t want to wind up like the Neanderthals, we need to band together and work together to create a more sustainable future. The loss of the Neanderthals teaches us that we should never take our existence for granted.

Peter C. Kjaergaard, University of Copenhagen Professor of Evolutionary History and Director of the Natural History Museum of Denmark; Mark Maslin, UCL Professor of Earth System Science; and Trine Kellberg Nielsen, Aarhus University Associate Professor of Archeology and Heritage Studies

Leave a Reply