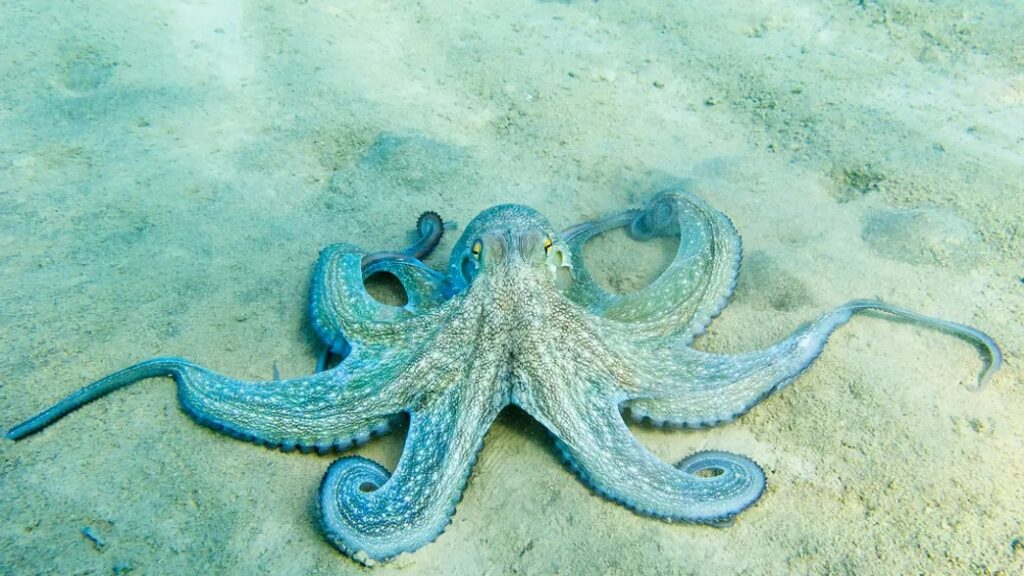

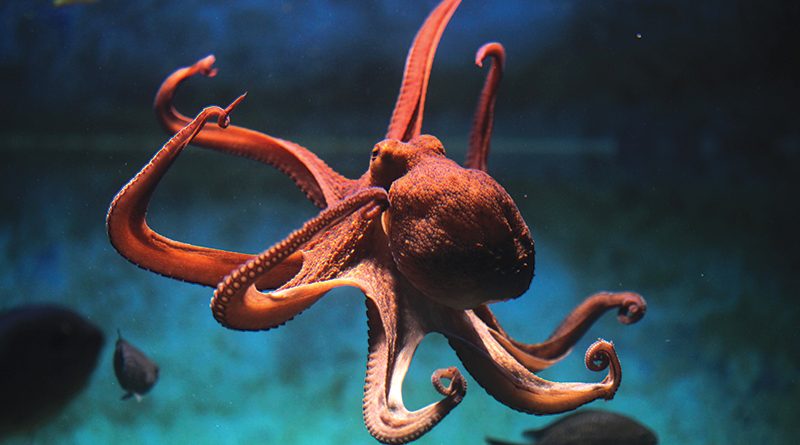

Humans are well-acquainted with the diverse spectrum of pain, from emotional distress to the physical discomfort of a stubbed toe. For invertebrates, pain was traditionally thought to be a simpler concept, primarily a reflex to correct bodily harm. However, a groundbreaking study has unveiled a different facet of pain perception in one of Earth’s most intelligent and charismatic invertebrates: the fish-punching octopus.

A recent study, set to appear in the journal iScience, delves into the pain experience of octopuses in a three-part exploration. The first part involved observing octopuses in a tank divided into chambers after they received various treatments. Octopuses subjected to a painful injection of acetic acid, known as AA, exhibited an aversion to the chamber where they received the painful treatment, even if that chamber had previously been their preferred space. In contrast, those receiving painless saline injections did not display any alteration in their chamber preferences. Furthermore, octopuses in ongoing pain could transform their least-favored chamber into a preferred space if they received pain relief in the form of a lidocaine injection while inside. This avoidance or attraction to chambers based on pain and pain relief implies that octopuses have negative emotional responses to pain, which they use to navigate their environment and avoid discomfort.

The second part of the study sought to determine whether octopuses could localize the site of discomfort or if pain response behaviors were systemic, regardless of the injury’s location. Octopuses were injected with AA in one arm, while others received lidocaine and saline injections. Those injected with AA displayed directed and sustained pain responses, often grooming the injured area with their beaks for up to twenty minutes, even removing the skin around the injection site in some cases. Conversely, those receiving the other two treatments either exhibited no response or briefly groomed the injection site.

In the final part of the research, intriguing parallels between mammals and cephalopods emerged. When mammals experience limb injuries, neural activity related to pain occurs in the central brain, which is remotely connected to the injury site. In a surprising revelation, this pattern was also observed in cephalopods, and thus far, they are the only invertebrates known to replicate such mammalian-like neural patterns. This finding adds a layer of complexity to the understanding of octopus pain perception, considering their unique brains extending into their limbs.

To test whether octopuses indeed process pain in a similar manner, researchers conducted electrophysiological recordings to trace neural activity following AA injection and its subsequent cessation with lidocaine. The results confirmed that pain in the arm triggered prolonged neural activity, which was swiftly silenced by the introduction of pain relief at the same site as the AA injection.

These findings have significant implications, as they offer robust support for the existence of a lasting, negative emotional state in octopuses. This marks the first evidence of pain experience in this neurologically complex group of invertebrates. The study’s conclusions raise important questions concerning the welfare of cephalopods and, by extension, other invertebrate species that may experience lasting pain due to tissue injury. These findings challenge conventional ideas and raise ethical concerns, particularly in the context of proposals for octopus farming, driven by increased demand for their meat.

Leave a Reply