Megachile pluto is the size of a honeybee, but it’s four times bigger.

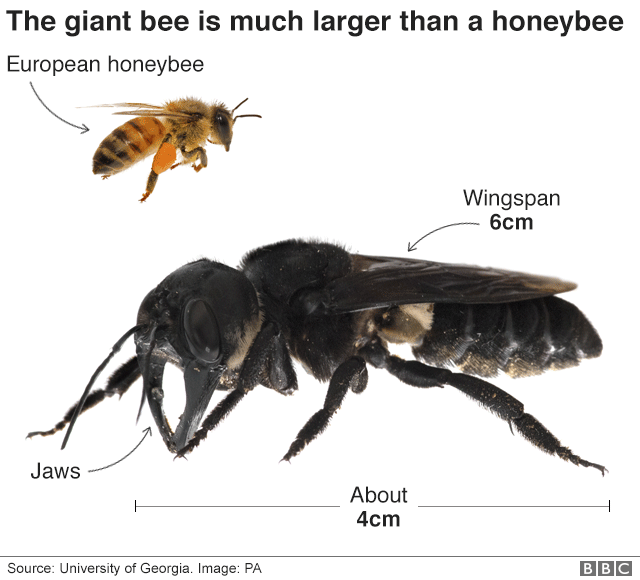

Alfred Russel Wallace, a renowned naturalist, discovered the Megachile pluto, the world’s largest bee, while exploring the lonely island of Bacan in the North Moluccas, Indonesia, in 1859. The bee, which is almost four times the size of a honeybee, is described by Wallace as a “huge black wasp-like insect, with gigantic teeth like a stag-beetle.” For more than a century, though, that was the only reported sighting of the Megachile pluto, and some speculated that deforestation had wiped out the huge bug.

Biologist Adam Messer discovered six Megachile nests on Bacan and adjacent islands in 1981, a sight so uncommon that residents said they’d never seen the nests before. For decades, it would be the only known sighting.

Then, a few years ago, Wallace’s huge bee was rediscovered by Eli Wyman, an entomologist at the American Museum of Natural History, and wildlife photographer Clay Bolt. In early 2018, the pair learned that a Megachile specimen was sold for $9,000 on eBay, reigniting their desire to travel to Indonesia in search of the bee.

“We decided that we had to go there,” Bolt told Earther. “Number one, to see it in the wild, to document it, but also to make local contacts in Indonesia that could begin to work with us as partners to try and figure out how to protect the bee.”

Wallace’s enormous bee was rediscovered in January by Clay, Wyman, and other researchers, this time in a termite nest in a tree.

“Seeing this ‘flying bulldog’ of an insect that we weren’t sure existed any longer was really breathtaking,” said Clay Bolt, the photographer who captured the first photographs of the species alive, to the BBC. “To witness how gorgeous and large the species is in person, to hear the sound of its massive wings thrumming as it went past my head, it was just wonderful.”

ANxiety about igniting a collector’s frenzy

Scientists and conservationists think that the presence of a single female in the wild indicates that the giant bee population in the region’s woodlands is still viable. One concern is that the news would cause a craze among collectors who are willing to spend a lot of money for rare examples.

“We know that putting the news out about this rediscovery could seem like a big risk given the demand, but the reality is that unscrupulous collectors already know that the bee is out there,” Robin Moore, a conservation biologist with Global Wildlife Conservation, told The Guardian. “By making the bee a world-famous flagship for conservation we are confident that the species has a brighter future than if we just let it quietly be collected into oblivion.”

WHY IS IT DIFFICULT TO DETERMINE WHEN A SPECIES IS EXTINCT?

In brief, determining when a species has gone extinct is tough since the world is vast, conservation resources are few, and it’s difficult to prove a negative.

“It all boils down to the challenge of definitively proving something does not exist,” Gary Langham, chief scientist for the National Audubon Society, an environmental organization, told Audubon.org. “It’s much easier to prove something does exist.”

It’s also easier for biologists to maintain track of huge animal populations — such as the northern white rhino, whose last male died in 2018 — than it is for small birds or insects. Scientists must often rely on more indirect methods to determine population numbers for some animals, such as collecting data on habitat damage, collecting sighting reports, and investigating materials left behind by the animals, such as droppings or nests. Because these surveys are so difficult, it’s rarely enough to declare a species extinct just because no one has seen it in 50 years.

“It’s a thing that keeps getting perpetuated, that there’s a 50 year rule,” Craig Hilton-Taylor, head of the Red List unit at the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), told the BBC.