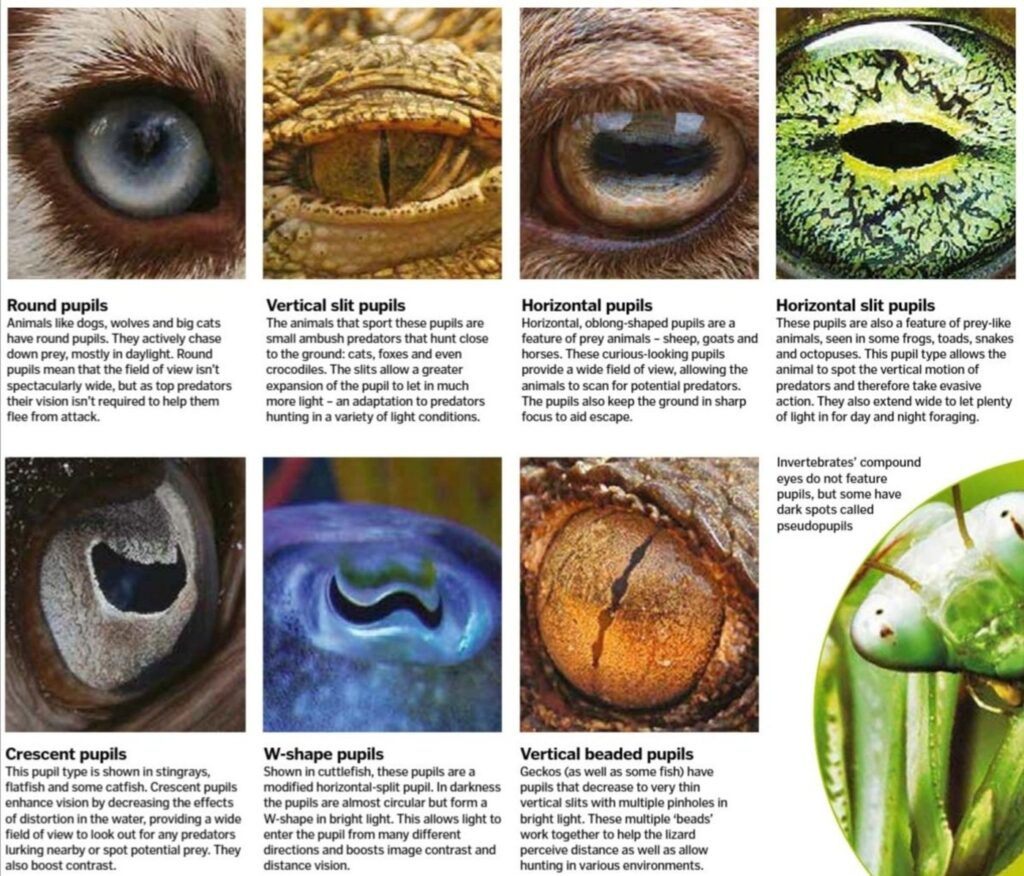

Given their close kinship, wolves and foxes have many traits in common. However, wolves have round pupils like humans, whereas foxes have a thin vertical line for a pupil. Pupils come in all different sizes and shapes throughout the animal kingdom, not just in canines. So why the variations?

It’s a query that has long piqued the curiosity of vision and optics researchers. My colleagues from Durham and Berkeley and I have just published a new study in the journal Science Advances that explains how these pupil shapes came to be.

Numerous other animals, including domestic cats, goats, sheep, and horses, have pupils that can range from being completely circular in dim light to being narrow slits or rectangles in bright light. Elongated pupils enable better control of the amount of light entering the eye, according to the accepted theory for this phenomenon. For example, a domestic cat’s pupil can change in size from fully dilated to fully constricted by a factor of 135, whereas a human’s round pupil can only change in size by a factor of 15. This is especially helpful for animals that are active both during the day and at night because it improves vision in low light.

However, if regulating the amount of light entering the eye were the only benefit of elongated pupils, the orientation would not matter because all of them—horizontal, vertical, or diagonal—would provide the same benefits. Instead, the pupils are typically horizontal or vertical, indicating that there must be additional advantages that account for this orientation.

Pupils fit for every niche

Our work has focused on the visual benefits of vertical and horizontal pupils in mammals and snakes. One of the most interesting factors we found is that the orientation of the pupil can be linked to an animal’s ecological niche. This has been described before, but we went one step further to quantify the relationship.

We found animals with vertically elongated pupils are very likely to be ambush predators which hide until they strike their prey from relatively close distance. They also tend to have eyes on the front of their heads. Foxes and domestic cats are clear examples of this. The difference between foxes and wolves is down to the fact wolves are not ambush predators – instead they hunt in packs, chasing down their prey.

In contrast, horizontally elongated pupils are nearly always found in grazing animals, which have eyes on the sides of their head. They are also very likely to be prey animals such as sheep and goats.

We produced a computer model of eyes which simulates how images appear with different pupil shapes, in order to explain how orientation could benefit different animals. This modelling showed that the vertically elongated pupils in ambush predators enhances their ability to judge distance accurately without having to move their head, which could give away their presence to potential prey.

Grazing animals must deal with a variety of issues. They must search every direction for prey and have a quick escape route in case of attack. Their ability to see almost everywhere around them is aided by having eyes on the side of their head. The amount of light they can receive from in front of and behind them is increased with a horizontal pupil, while the amount they can receive from above and below is decreased. They can see the entire surface thanks to this, which aids in the earliest possible detection of potential predators. The horizontal pupil also improves the image quality of horizontal planes, which is advantageous when running quickly to get away from something.

Therefore, horizontally elongated pupils aid prey animals in avoiding their predators, while vertically elongated pupils aid ambush predators in capturing their prey.

We realized that, compared to taller animals, shorter animals should benefit more from vertical pupils. As a result, when we double-checked the data on animals with frontal eyes and vertical pupils, we discovered that 82% of them fall under our definition of “short” (shoulder height less than 42 cm), as opposed to only 17% of those with circular pupils.

We also realised that there is a potential problem with the theory for horizontal elongation. If horizontal pupils are such an advantage to grazing animals, what happens when they bend their head down to graze? Is the pupil no longer horizontally aligned with the ground?

We checked this by observing animals in both a zoo and on farms. We found that eyes of goats, deer, horses, and sheep rotate as they bend their head down to eat, keeping the pupil aligned with the ground. This remarkable eye movement, which is in opposite directions in the two eyes, is known as cyclovergence. Each eye in these animals rotates by 50 degrees, possibly more (we can only make the same movement by a few degrees).

There are still some unexplained pupils in nature. For example, mongooses have forward-facing eyes but horizontal pupils, geckos have huge circular pupils when dilated which reduce down to several discrete pinholes when constricted and cuttlefish have “W”-shaped pupils. Understanding all these variations is an interesting challenge for the future.

Leave a Reply