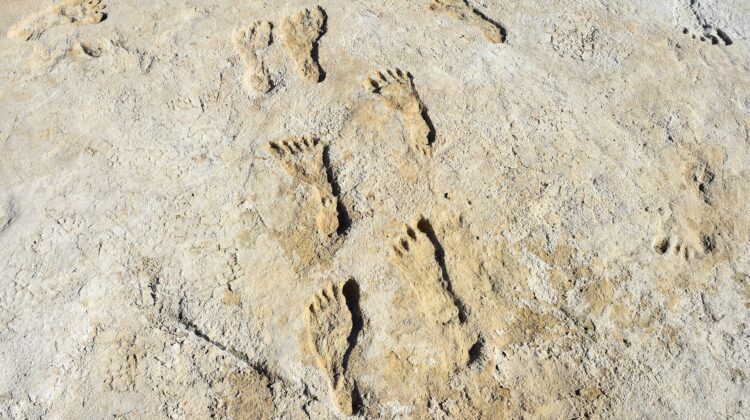

In a groundbreaking discovery, ancient footprints unearthed in White Sands National Park, New Mexico, are challenging the established narrative of human migration to North America. These remarkable imprints, dating back 22,000 to 23,000 years, suggest that humans were present on the continent much earlier than previously believed—by a staggering 7,000 years.

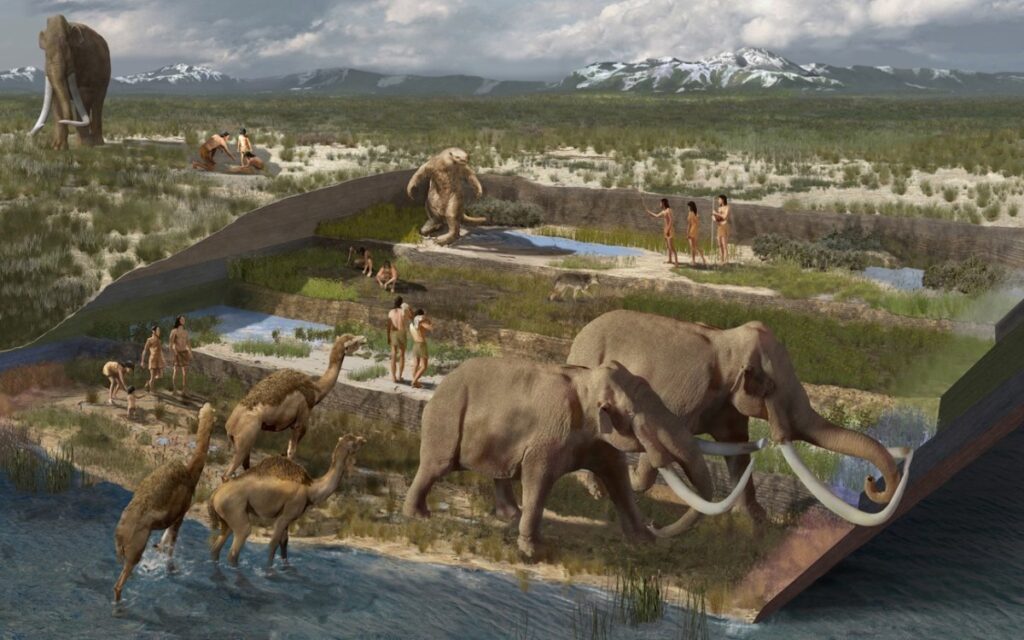

The findings, detailed in a recent study published in the journal Science, reveal a complex tapestry of human life during the last ice age. Discovered in the dried-up bed of Lake Otero, which thrived during this glacial period, the footprints coexist with tracks of mammoths, ground sloths, camels, dire wolves, American lions, and other extinct megafauna. The lake served as a vital source of food and water for both animals and humans.

The initial discovery in 2018 astonished researchers, who identified hundreds of human footprints exhibiting signs of activities such as running, jumping, and carrying heavy loads. These footprints provided a unique window into the lives of ancient inhabitants.

To ascertain the age of these footprints, scientists initially used radiocarbon dating on seeds from the aquatic plant Ruppia cirrhosa, present in the layers of earth surrounding the footprints. However, concerns were raised about potential inaccuracies due to the plant’s growth in the lake, absorbing carbon-14 from the water.

In response, the research team revisited the site, collecting new samples focusing on pollen extracted from sediment layers associated with the footprints. By isolating and radiocarbon dating pollen from terrestrial pine trees, and utilizing optically stimulated luminescence (OSL) analysis on quartz grains from a clay layer, they unveiled surprising results.

The pollen dates back to a range of 23,000 to 21,000 years, while the OSL analysis indicates that the quartz grains were buried between 21,400 and 18,000 years ago. These revelations push the age of the footprints back by at least 7,000 years, challenging the widely accepted theory that humans entered the Americas around 16,000 years ago via a land bridge connecting Siberia and Alaska.

Kathleen Springer, a USGS geologist, expressed the significance of this discovery, stating, “It’s a paradigm-shattering result.” The revelation challenges existing ideas about migratory routes and human movements during the Last Glacial Maximum, the peak of the last ice age.

The footprints not only redefine the timeline of human presence but also offer insights into the lifestyle and behavior of ancient humans in a harsh environment. Sixty-one footprints, predominantly from teenagers and children, suggest a division of labor. Adults may have engaged in skilled tasks near the lake, while teenagers handled activities such as fetching and carrying, as evident in their more abundant footprints. The smaller footprints of young children likely reflect playful activities.

Some footprints reveal interactions between humans and ice age animals. In one set, human footprints suggest individuals stalking a giant sloth. Unfortunately, there is no evidence of a successful outcome from this ancient hunt.

The researchers anticipate further exploration at White Sands National Park, believing more footprints await discovery. Their hope is that these findings will inspire additional research at sites across the Americas, unraveling more clues about the early history of human migration and settlement. The 23,000-year-old footprints at White Sands are rewriting the narrative of North America’s ancient past, inviting us to reconsider the depth of human history on the continent.

Leave a Reply