Late 19th-century London was not only about grand mansions, clattering carriages, and elegant ladies in hats. It was also a city where thousands struggled every day just to spend the night under a roof instead of beneath cold rain.

In the era of late Victorian England, even sleep was a commodity. The poor paid for it as they would for a piece of bread or a mug of beer. And this strange business had its own “tariffs.”

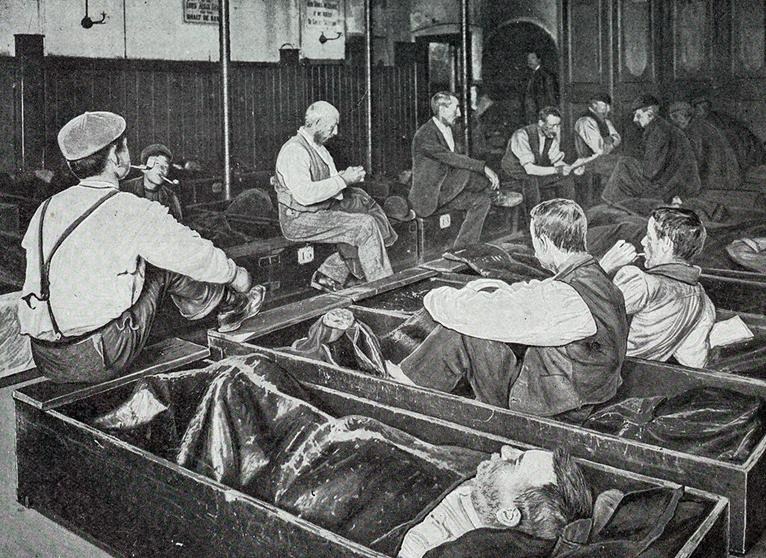

The Four-Penny “Coffin”

For four pence—a sum that seems symbolic today but could have been a day’s wage for a street porter—a person could spend the night in a so-called four-penny coffin.

These were long, narrow wooden boxes just wide enough to stretch out in. They resembled real coffins—without lids but with high sides. Sometimes straw or an old blanket was placed at the bottom, but more often it was just bare planks.

These shelters weren’t free charities—they were small businesses. Owners maintained dozens, sometimes hundreds, of such “beds” in basements or backyards. For a homeless person who had earned a few coins, it was a chance to sleep lying down and in relative warmth.

The Two-Penny “Rope”

But what if someone had only a couple of coppers? Then they went to a flophouse with even more dubious comfort—the two-penny “rope bed.”

There was neither a bed nor even a box. A thick rope stretched across the room at chest height, above a long backless bench.

The lodger sat on the bench, leaned forward onto the rope with his chest and arms, and fell asleep half-folded. In the morning the keeper simply cut or loosened the rope—and the “guests” woke up, often tumbling forward.

Did the Word “Hangover” Come from This?

Some say this practice gave rise to the word hangover. Historians disagree: originally, the English term meant “something left unfinished” or “a relic of the past,” later shifting to the painful after-effects of drinking.

Still, the “rope night” did feel like a hangover: stiff arms, aching back, a heavy head, and general exhaustion.

Why Did This Exist?

At first glance, such a “service” seems cruel. But for many poor Londoners it was better than sleeping outdoors. The city was damp and cold; in winter the temperature could drop below freezing, and a man soaked by rain risked dying of exposure.

The flophouses were also safer than the street: inside, one was less likely to be picked up by the police, who could arrest vagrants for “loitering.”

Who Slept in the Coffins and on the Ropes?

Clients weren’t only the chronically homeless. Among them were:

- seasonal laborers who came to London for work,

- sailors between voyages,

- the unemployed waiting at morning hiring markets,

- poor pensioners,

- women left destitute after losing their breadwinners.

For some it was a temporary refuge; for others, a habitual place of sleep for years.

Stench, Noise, and Crowds

According to eyewitnesses, nights in such shelters were far from restful. The air reeked of sweat, smoke, cheap tobacco, and dirty clothes. People coughed, tossed, and in rope houses, sleepers slid off the ropes, waking others.

And yet, for many, these few hours of rest were the only way to survive the night.

The End of the “Rope Bed” Era

By the early 20th century, things began to change. Under pressure from the public and charities, London introduced municipal shelters where one could spend the night free of charge, albeit in shared dormitories.

The rope flophouses disappeared, and the four-penny coffins remained in memory as a symbol of poverty and the harsh realities of the Victorian era. Today, only old photographs and eyewitness accounts recall them.

What This Story Tells Us

The tale of the “two-penny sleep” reminds us how deep the social divide can be even in wealthy cities. Victorian London boasted progress and imperial power, yet thousands of its residents lived on the edge of survival, buying themselves the right to a few hours of rest.

And perhaps such stories help us value the simplest things—warmth, safety, and the chance to lie down to sleep without wondering whether we can afford it.

Leave a Reply