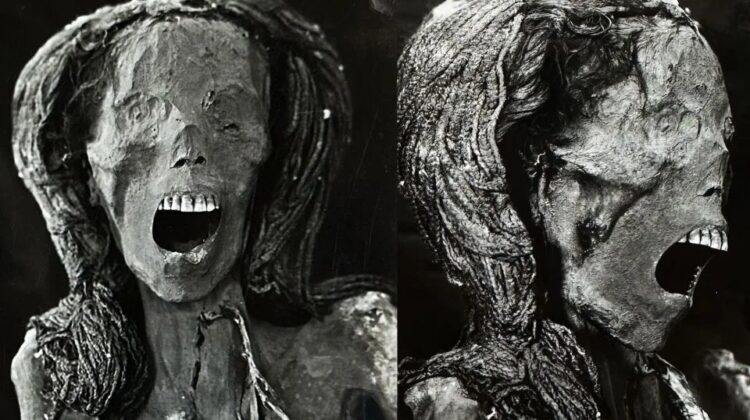

In 1935, archaeologists discovered the mummified remains of an ancient Egyptian woman near Luxor, her mouth frozen wide open in what seemed to be a scream. This “screaming woman,” who lived about 3,500 years ago, has continued to intrigue scientists. Recently, a team of researchers used advanced techniques to uncover new details about her life, health, and the cause behind her dramatic facial expression.

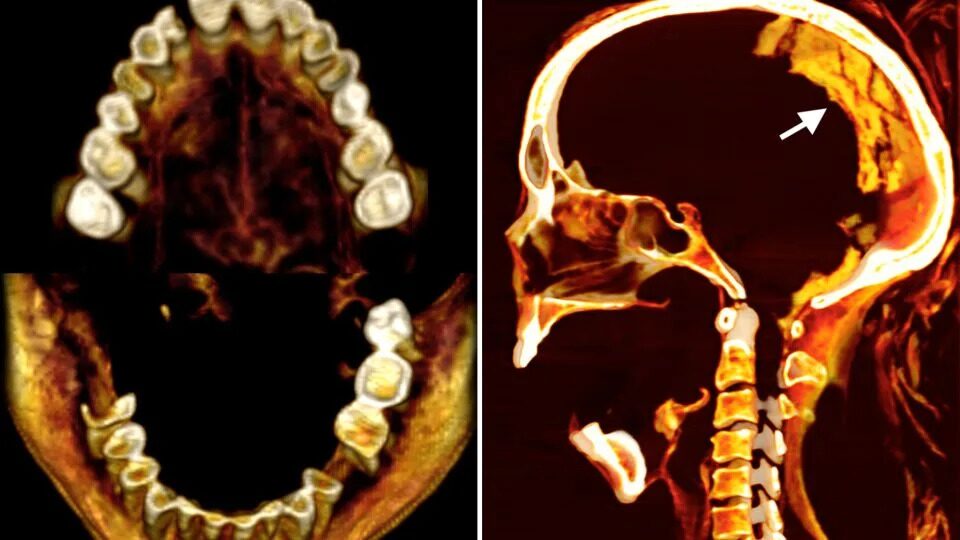

Their study, published Friday in Frontiers in Medicine, utilized CT scans and infrared imaging to analyze the mummy’s morphology and preservation. They found that the woman was 48 years old at the time of her death, as indicated by the analysis of a pelvic joint. Notably, her body was embalmed using frankincense and juniper resin—valuable substances traded from afar—suggesting a high level of care in her mummification process.

Study author Sahar Saleem, a professor of radiology at Kasr Al Ainy Hospital at Cairo University, noted that the mummy had no visible incisions, which aligns with the original discovery that her internal organs were intact. This finding is unusual because the classic mummification technique from that era typically involved the removal of all organs except the heart.

The researchers determined that the woman stood 1.54 meters (a little over 5 feet) tall and had mild spinal arthritis, with bone spurs present on some vertebrae. Several teeth were missing from her jaw, likely lost before her death. Despite these details, the exact cause of her death remains unclear.

Saleem emphasized that the use of costly, imported embalming materials and the mummy’s well-preserved state contradicts the notion that the presence of internal organs indicated poor mummification practices. The study also highlighted that open-mouthed mummies are rare, as embalmers typically wrapped the jaw and skull to keep the mouth closed.

One hypothesis proposed by the researchers is that the woman’s open mouth could be a result of a cadaveric spasm—a rare muscular stiffening linked to violent deaths, suggesting she might have died in agony or pain. It’s also possible that she was mummified within 18 to 36 hours of death, which would have preserved her open mouth position. However, the study notes that a mummy’s facial expression doesn’t necessarily reflect the deceased’s final moments, as factors like decomposition and drying out can influence it.

The woman was buried beneath the tomb of Senmut, an architect for Queen Hatschepsut, and may have been related to him. Her remains were discovered during an expedition led by the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and her coffin is currently on display there, while her mummified body resides at the Cairo Egyptian Museum.

Saleem, who has previously studied other open-mouthed mummies, found that one such mummy, thought to be a prince named Pentawere, had his throat slit and showed signs of poor embalming. Another, Princess Meritamun, had a wide mouth attributed to postmortem jaw movement.

Cardiologist Randall Thompson, who has studied ancient mummies to explore the origins of cardiovascular disease, praised the study for its detail and insight. He noted that the research helps us understand ancient substances and their uses, shedding light on health and disease across millennia. “Heart disease is older than Moses,” Thompson remarked, highlighting the value of such historical studies.

Leave a Reply