Nestled in the wild, untamed waters of the North Atlantic lies St. Kilda, an isolated archipelago approximately 41 miles (66 km) west of Scotland’s Outer Hebrides. Known as one of the most remote areas in the British Isles, St. Kilda was home to a resilient and resourceful community for over 2,000 years. This unique settlement, built on the back of seabirds, sheep, and small-scale farming, tells a story of survival, adaptability, and ultimately, decline.

The Simple Life of St. Kilda

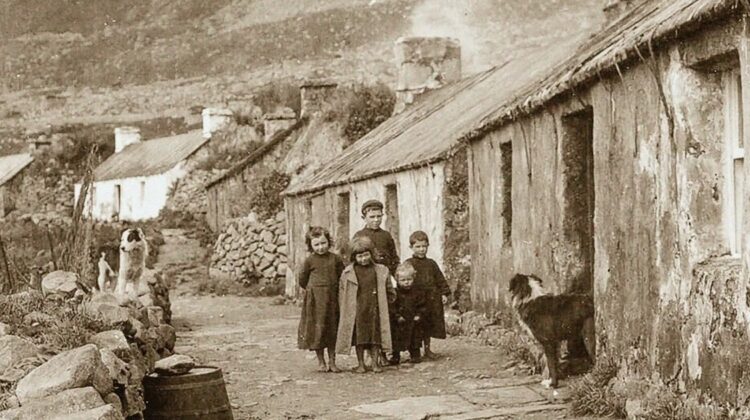

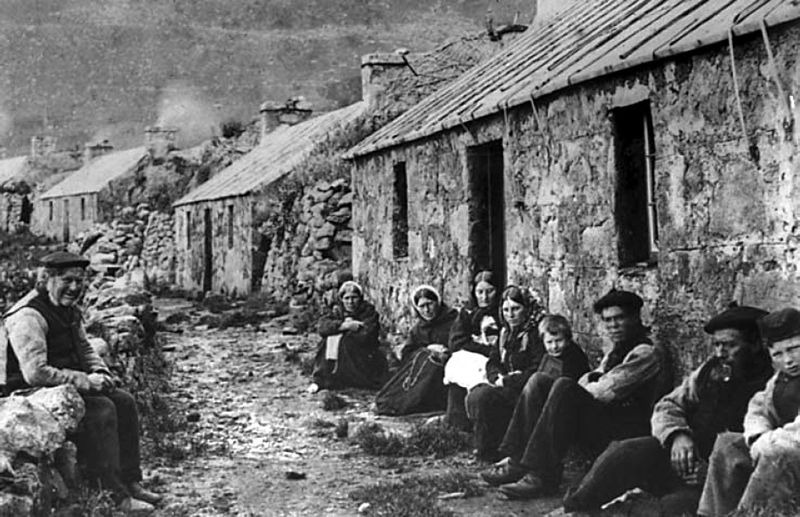

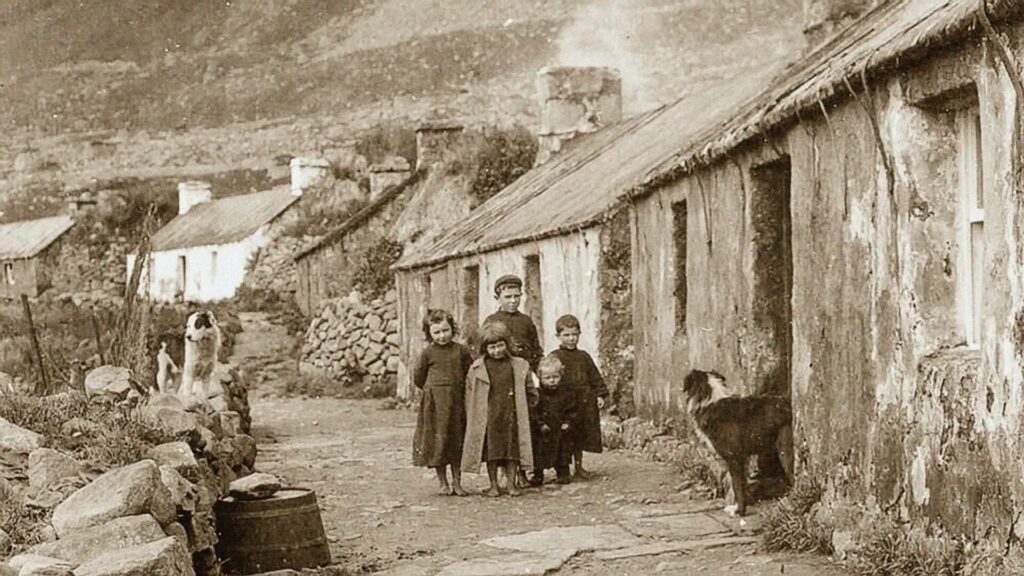

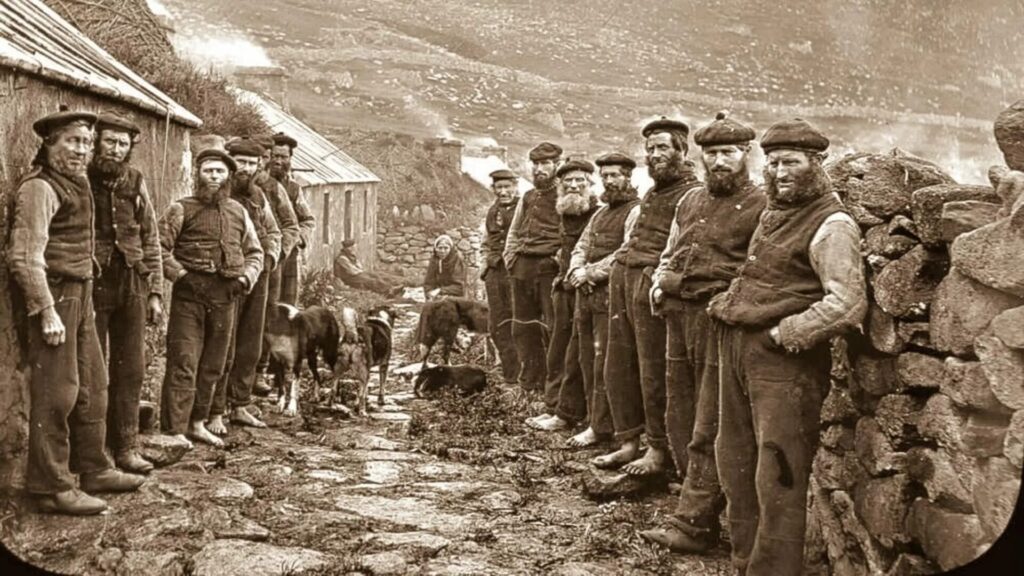

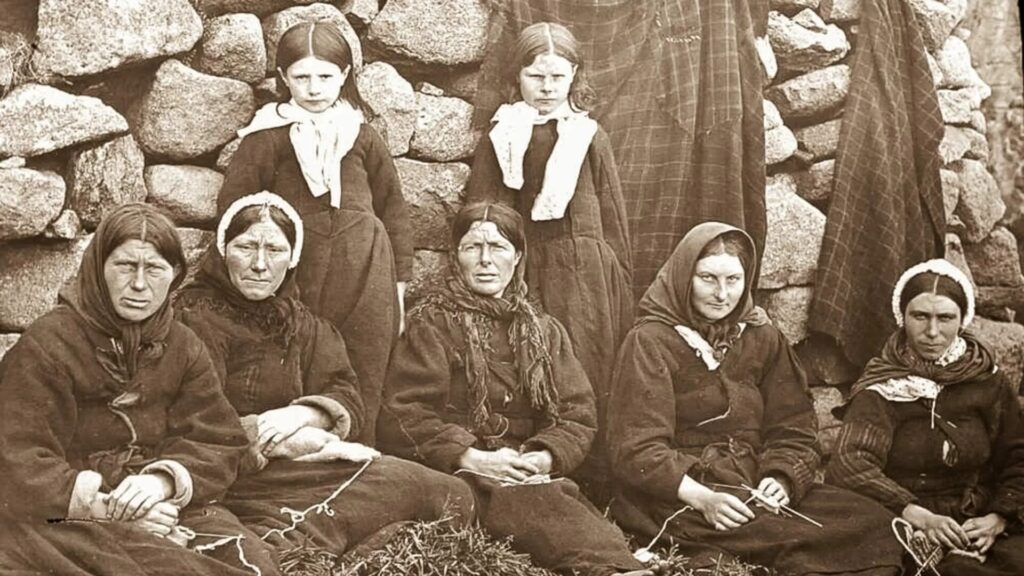

In the 1860s, life on St. Kilda revolved around its simple stone houses, referred to as the “main street,” which were constructed to replace older blackhouses destroyed by a hurricane. These cottages, built with chimneys and slate roofs, were a testament to the islanders’ resourcefulness. Despite its harsh environment, the islanders practiced crofting, a form of subsistence farming involving livestock and small-scale agriculture.

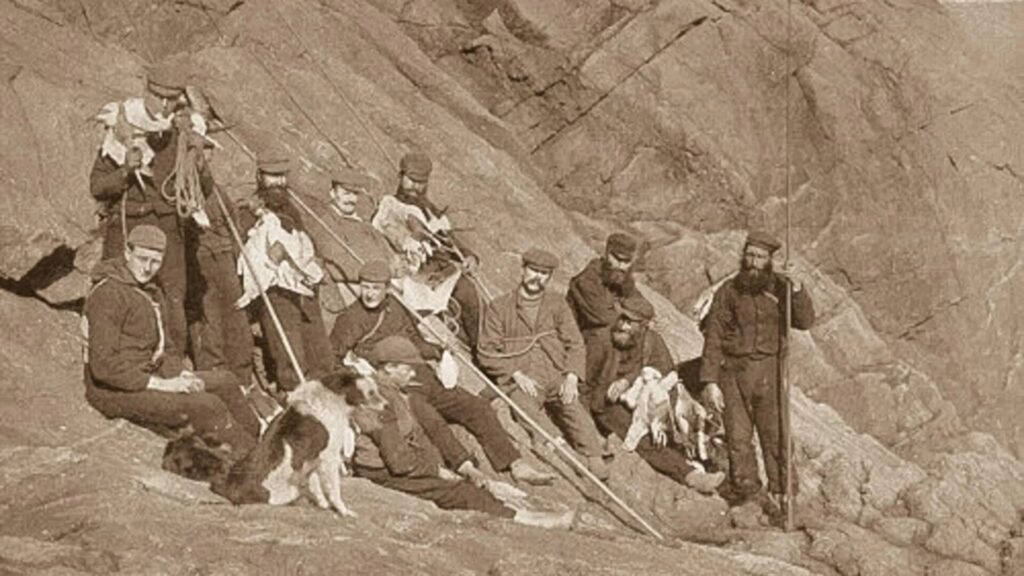

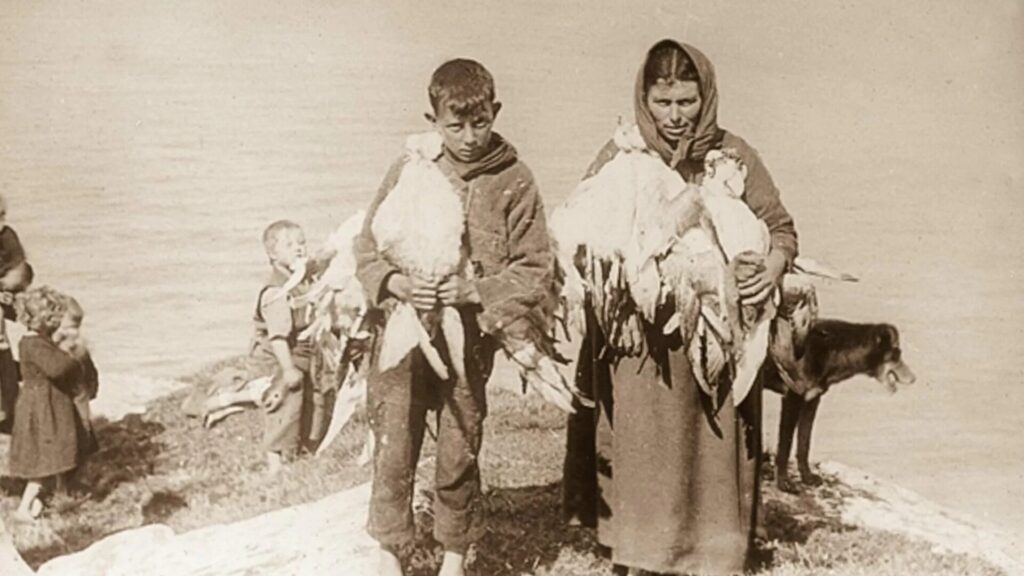

Seabirds formed the cornerstone of their diet, as the treacherous waters surrounding the islands made fishing a dangerous endeavor. Gannets, fulmars, and puffins were harvested in large numbers, their feathers used for trade, and their eggs and meat consumed for sustenance.

Dogs were an integral part of life on St. Kilda, assisting in herding sheep and hunting seabirds. The islanders’ physical resilience, shaped by the demands of their environment, was remarkable—St. Kildan men were known to have unusually thick ankles and agile feet, a result of their constant cliff-climbing pursuits.

Challenges of Isolation

St. Kilda’s isolation brought both advantages and perils. While it protected the community from outside influences for centuries, it also left them vulnerable to diseases. Visitors and tourists, arriving on faster steamships in the late 19th century, introduced illnesses such as cholera, tetanus, and even the common cold, which proved deadly to the islanders.

By the early 20th century, the population began to decline drastically. World War I, economic hardships, and the lure of modern amenities on the mainland contributed to their diminishing numbers. In 1930, the remaining 36 residents petitioned for evacuation, citing the harsh living conditions and an inability to sustain their community.

St. Kilda Today

Today, St. Kilda is uninhabited by permanent residents but remains a dual UNESCO World Heritage Site, celebrated for its natural and cultural significance. The Soay sheep, thought to be direct descendants of sheep brought to the islands thousands of years ago, now roam freely. Seabird colonies continue to thrive on its cliffs, including puffins, gannets, and fulmars, which are monitored by researchers.

Although its human population is gone, the archipelago’s legacy lives on. The story of St. Kilda serves as a poignant reminder of humanity’s enduring connection to nature and the resilience required to survive in some of the most unforgiving environments on Earth.

Leave a Reply