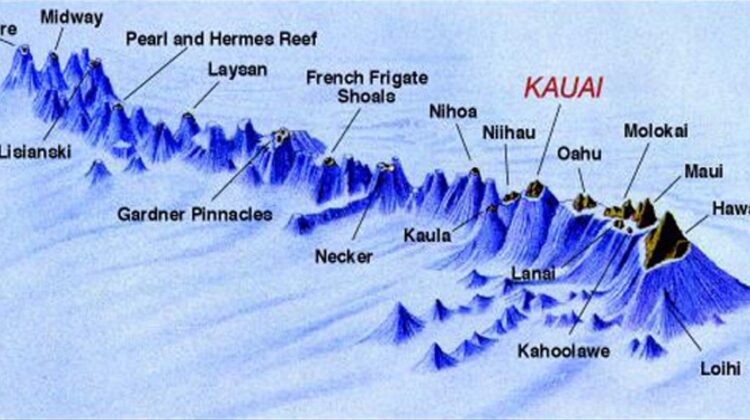

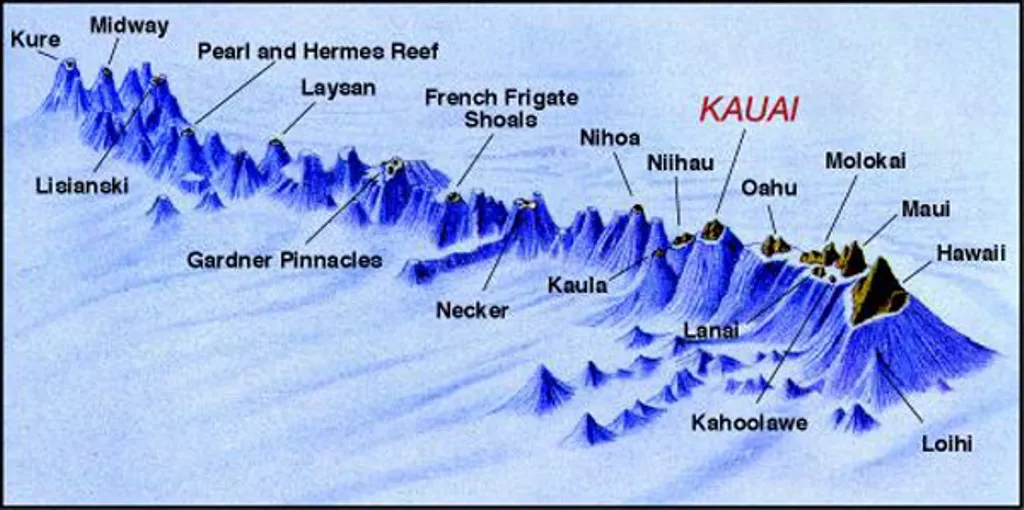

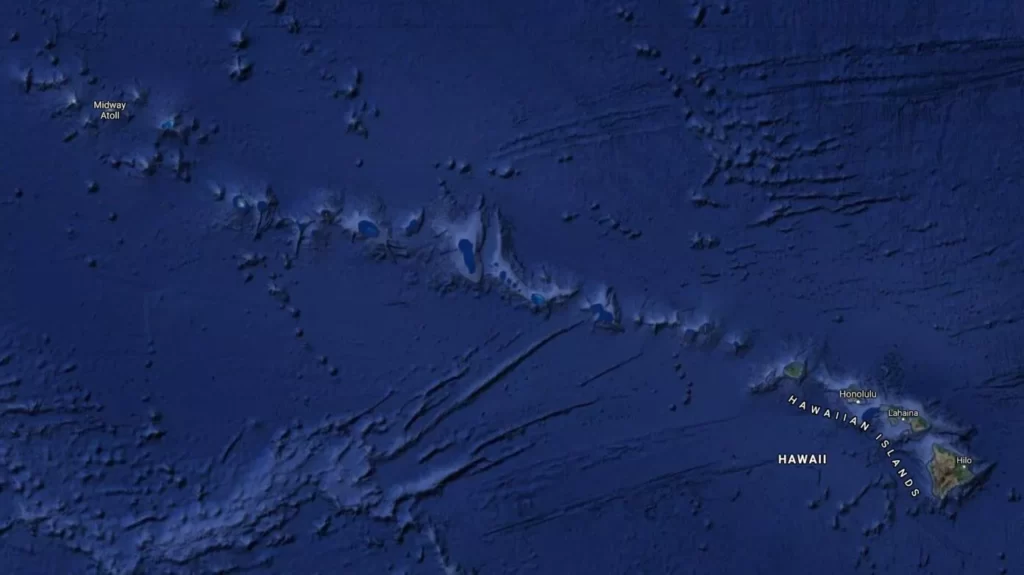

The Pacific Plate is migrating northwestward at a rate similar to that of your fingernails – several millimeters each year. This continuous plate movement over a local volcanic “hot spot,” or plume, has resulted in an assembly-line-style chain of volcanic islands. They are known (really) as Hawaii.

The Hawaiian Islands (also known as the Hawaiian archipelago) are made up of eight major islands and 124 islets that run 1,500 miles northwest from the Big Island of Hawaii to Japan and the Aleutian Islands of Alaska, at the centre of the “Pacific Plate” on top of a “hot spot.” The islands have a combined size of 6,459 square miles.

The Big Island is now the biggest landmass in the Hawaiian island chain (although this may alter over time), followed by the other seven main islands at the chain’s eastern end, from west to east: Ni’ihau, Kaua’i, Oahu, Molokai, Lanai, Kahoolawe, and Maui.

Hawaii, the newest island in the chain, sprang from the seafloor over a million years ago as five different volcanoes. By erupting repeatedly, the five volcanoes formed thin layers of lava that built up over time, until the volcanic heads rose from the water – eventually becoming today’s Hawaii.

But how did five volcanoes come together to form one island? They most likely erupted at separate periods, causing flows that merged with the flows of the other mountains, eventually resulting in the five summits constituting the singular island we see today.

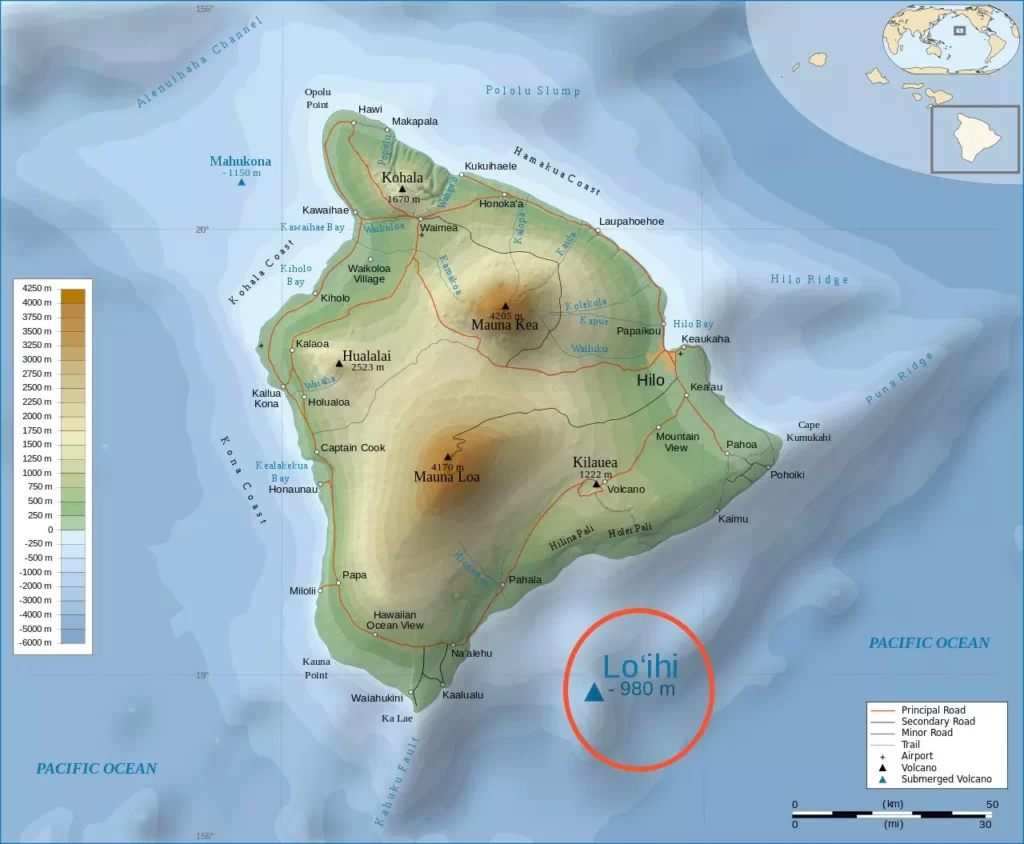

By siting above the ‘hot point’ on the plate, the Kohala Mountains were the first to develop. The position of the rising magma altered as the plate migrated, going to Mauna Kea, Hualalai, Mauna Loa, and finally Kilauea.

Since then, the procedure hasn’t slowed down! Loi’hi, the newest seamount, is now developing off the Big Island’s southeast coast (see second map above and read more about Loi’hi below). In another 50,000 years or so, it might become the next Hawaiian island, or it could even join the Big Island’s sixth peak. Only the volcanic relics of Kohala are still active and will never erupt again. The remainder of the Big Island’s volcanoes aren’t nearly ready yet!

Mauna Loa, the Big Island’s biggest volcano, covers about 51 percent of the island. Even yet, most people have a difficult time identifying it since the shield form makes it difficult to discern if you’re looking at a real mountain.

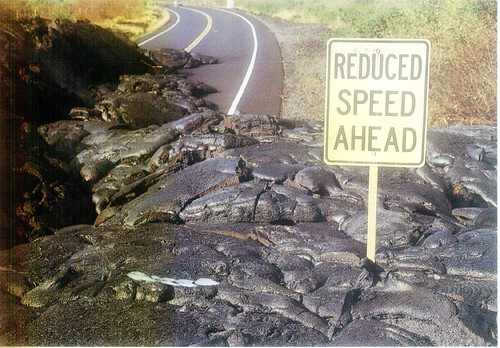

In fact, all of Hawaii’s volcanoes are called “shield volcanoes” because of their likeness to a warrior’s shield. Molten lava rises from a hot place in the Earth’s crust and erupts from different vents and rifts on the surface, finally flowing down the gentle slopes into the ocean, layer by layer, over millions of years.

Kilauea, the world’s most active volcano and home to the fire-goddess Pele, is located on the eastern slopes of Mauna Loa. Kilauea was once thought to be a vent of Mauna Loa, but it has now been discovered that it has its own magma chamber and is fully independent of its bigger relative.

Mauna Kea, the island’s other main volcano, covers nearly a quarter of the island’s entire landmass. Mauna Kea is more simpler to detect than Mauna Loa, and is easily identified in the winter months by its snowy crown, which is how it received its name (Mauna Kea meaning “White Mountain”). Now here’s an unusual statistic about this volcano: it is the highest point in the Pacific Ocean and the world’s tallest mountain from base to peak, reaching a total elevation of 33,000 feet above the sea bottom, of which only 13,780 (approx.) feet exist above sea level!

Hualalai near Kailua-Kona on the west side of the island and Kohala on the northwest point of the island are the other volcanic mountains on the Big Island.

Kohala, the island’s oldest peak, has far greater geological damage than its younger cousins. The incredible sea cliffs you see now were most likely formed by a massive landslide 200,000 years ago.

The submarine volcano known as Lo’ihi is located just 18 miles off Hawai’i’s southeast coast, as previously noted. Lo’ihi is a seamount that is now erupting at a depth of 3,178 feet below the ocean’s surface.

When Lo’ihi rises from the sea, it will most likely combine with Kilauea (which, in theory, will be considerably larger by then) to become the sixth peak on Hawai’i’s biggest island. That won’t happen quickly, though; it’ll probably take 50,000 years or more. So hold off on booking your hotel stay.

The submarine volcano known as Lo’ihi is located just 18 miles off Hawai’i’s southeast coast, as previously noted. Lo’ihi is a seamount that is now erupting at a depth of 3,178 feet below the ocean’s surface.

When Lo’ihi rises from the sea, it will most likely combine with Kilauea (which, in theory, will be considerably larger by then) to become the sixth peak on Hawai’i’s biggest island. That won’t happen quickly, though; it’ll probably take 50,000 years or more. So hold off on booking your hotel stay.

Geologists think Haleakala formerly formed a continuous landmass with Lanai, Molokai, and Kahoolawe – known as Greater Maui – not just to the west of Maui, but also to the east (Maui Nui). The submergence of that landmass caused the volcanic body to move away from the Hawaiian hot spot, causing significant chunks of the Big Island to vanish into the Pacific. The four big islands that we see now are the outcome of this process.

The Big Island faces a similar destiny. The Big Island will succumb to subsidence and erosion as the Pacific Plate takes the islands piggyback-style to the north-west and the hot point “moves away,” eventually meeting the same fate as Maui Nui. As the ocean encroaches on the sides of each individual mountain, it will split into smaller islands.

The Big Island, on the other hand, will maintain that size for the next several thousand years! Mauna Loa and Kilauea volcanoes are continually active and erupting, therefore Hawaii’s island is still growing.

The islands’ geologic future is still being formed.