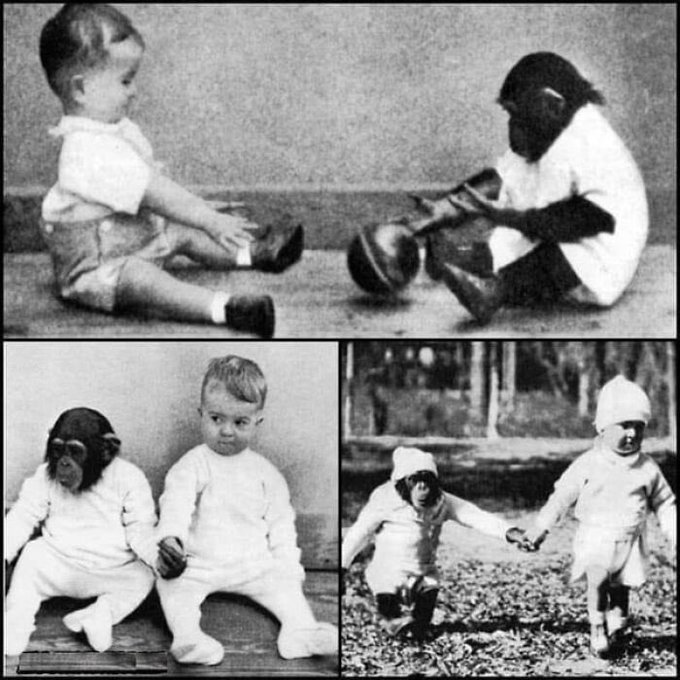

The story of Luella and Winthrop Kellogg’s extraordinary experiment in the early 20th century remains a captivating exploration of the boundaries between human and animal behavior. This groundbreaking experiment, which began in 1931, centered around their 10-month-old son, Donald, and a 7-month-old chimpanzee named Gua, whom they raised as “brother and sister.” The primary aim was to investigate whether Gua could acquire human behaviors and adapt to life in a human environment.

Winthrop Kellogg, a recent graduate of Columbia University’s psychology program, was the visionary behind this unique experiment. His interest was piqued by the stories of children who had been left in the wild and raised alongside animals, believing that their transformation was the result of environmental influence. Kellogg rejected the notion that such children were “feeble-minded” or had inherent genetic disorders. Instead, he proposed that environmental factors played a pivotal role in shaping their behaviors.

While he was keen to explore this theory further, Kellogg recognized the ethical and legal complexities of actively placing a child in the wild. Thus, he devised a different approach: instead of sending a child into the wild, he would place an animal in a typical human environment.

The concept was not without its challenges. To ensure the experiment’s validity, Kellogg set high standards. The chosen animal had to be an anthropoid, bearing a resemblance to a human, and it had to be young enough to adapt readily. The immersion in the human environment had to be complete, both psychologically and physically. Every individual who came into contact with the animal, Gua in this case, had to treat her as if she were a human child.

Kellogg articulated this approach by saying, “It is not unreasonable to suppose if an organism of this kind is kept in a cage for a part of each day or night if it is led about by means of a collar and a chain… That these things must surely affect the animal’s behavior.” The experiment was, in essence, designed to blur the line between the chimpanzee and the human, and to observe how closely Gua could mimic the behavior of her human “siblings.”

For nine months, the Kelloggs diligently carried out the experiment. During this period, Gua demonstrated remarkable progress in acquiring human behaviors. She often outperformed Donald in tasks like responding to simple commands and using utensils like a cup and spoon. It appeared that Gua was adapting to her human surroundings in a way that defied conventional expectations.

However, as the experiment reached its ninth month, an unexpected turn of events occurred. Donald began to copy Gua’s vocalizations and act more like a chimpanzee than a human child. The Kelloggs decided to conclude the experiment on March 28, 1932, as it became evident that their efforts to raise Gua as a human child had, in some way, led to Donald adopting more of Gua’s behaviors.

The Kellogg experiment, while unconventional and ethically complex, raised significant questions about the influence of environment on behavior. It challenged prevailing beliefs of the time and encouraged a broader examination of nature versus nurture in shaping the development of humans and animals. While this experiment is viewed differently through today’s ethical lens, it remains a thought-provoking chapter in the history of psychology and animal behavior research.

Leave a Reply