When we think of turtles, one of the first things that come to mind is their iconic shells. Unlike some animals that can retreat into their shells, like snails, turtles have their shells permanently attached to their bodies. But this extraordinary adaptation wasn’t always a part of their existence. Let’s dive into the fascinating journey of how turtles became their shells.

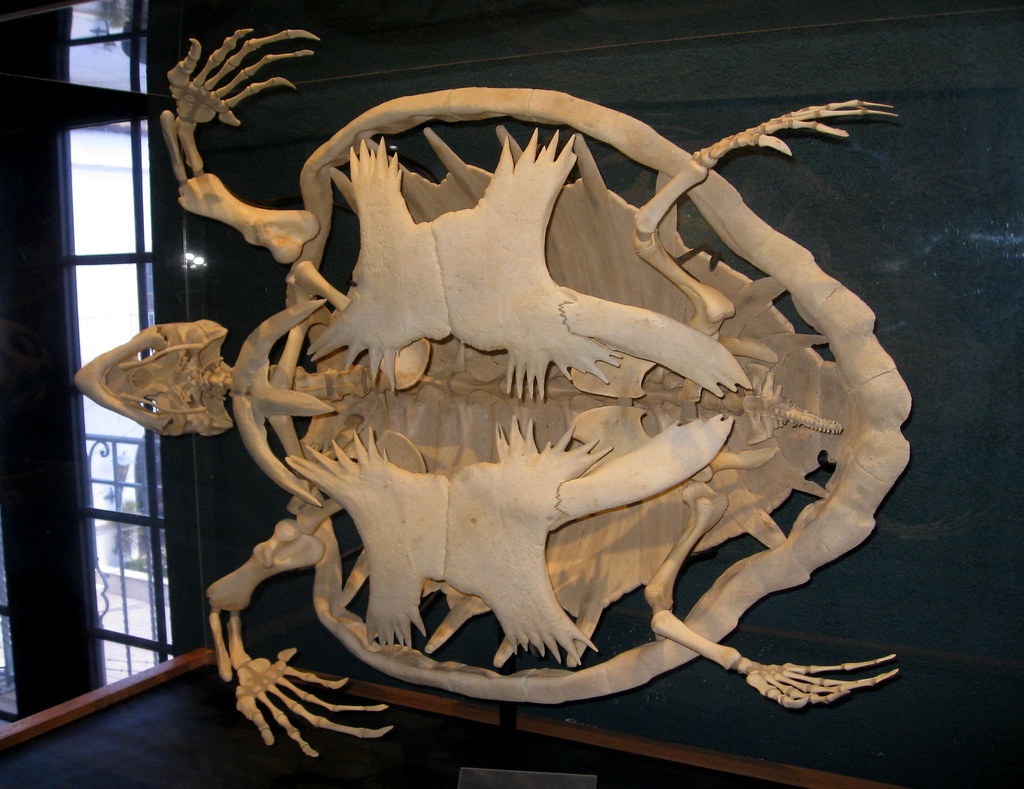

A turtle’s shell serves as more than just a protective covering; it’s a unique adaptation that safeguards vital organs from predators and environmental hazards while also playing a role in regulating the turtle’s body temperature. This remarkable structure consists of two main parts: the carapace (top) and the plastron (bottom), interconnected by a bridge.

Comprising approximately 50 bones, including ribs, shoulder bones, and vertebrae, the shell is covered by an outer layer of keratinous scutes, which provide additional protection and structure.

The evolution of the turtle shell has long intrigued scientists. How did the ancestors of turtles transform their flexible ribs and vertebrae into a rigid, protective shell? How did they manage to breathe and move with such a substantial structure? Recent studies have begun to shed light on these questions, drawing insights from fossil evidence and embryological development.

One of the earliest known turtle fossils, dating back roughly 260 million years, belongs to Eunotosaurus africanus. This reptile possessed a wide rib cage but lacked a shell. It also had a reduced number of vertebrae and ribs, suggesting adaptation for burrowing. Another ancient turtle ancestor, Odontochelys semitestacea, lived about 220 million years ago and had a fully developed plastron but only a partial carapace. Notably, it had teeth, a feature absent in modern turtles. These fossils reveal that the plastron evolved before the carapace, and initially, the shell served purposes beyond defense, such as digging.

The development of the carapace involved several morphological changes and shifts in gene expression within the ribs and vertebrae. While most vertebrates have rib-to-vertebrae joints that allow for chest cavity expansion during breathing, turtles have fused ribs and vertebrae, which form the carapace. This unique adaptation means that turtles rely on abdominal muscles to move their viscera for respiration.

The genes responsible for shaping the ribs and vertebrae in turtles differ from those in other vertebrates. For instance, the gene Tbx5, usually associated with forelimbs, is expressed in turtle ribs, contributing to their enlargement and flattening. Another gene, Fgfr2, typically involved in bone growth, is suppressed in turtle ribs, preventing excessive elongation.

The turtle shell stands as a remarkable testament to the power of natural selection in shaping complex structures from simpler ones. This extraordinary adaptation has enabled turtles to thrive across diverse habitats, from arid deserts to expansive oceans. As some of the oldest living reptiles, turtles owe much of their evolutionary success to their remarkable shells.

Leave a Reply