Animals with two heads? Yes, they appear in mythology and films, and we’ve heard a strange thing or two after nuclear disasters like Chernobyl, but isn’t that it? No, it does not. Scientists are only guessing as to why two-headed sharks are becoming more common around the world.

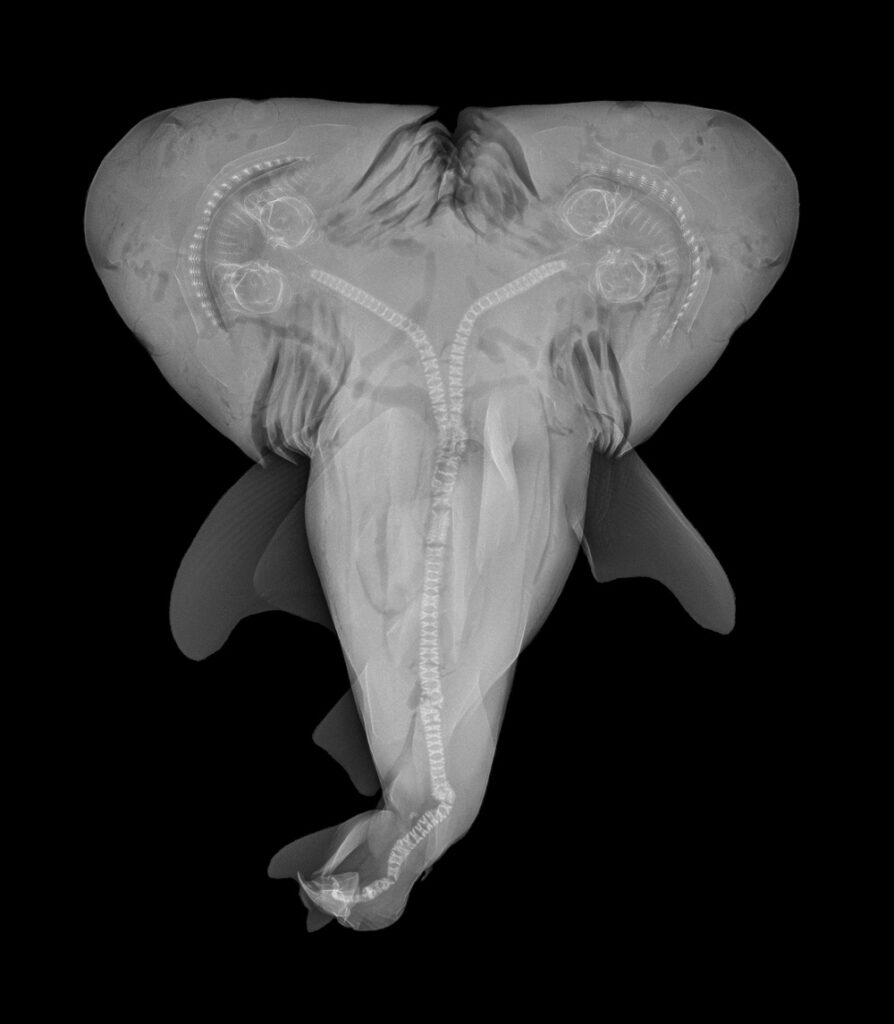

Longline fisherman Christopher Johnston was fishing in the Indian Ocean roughly 200 to 900 miles off the coast of West Australia in 2008 when he caught a pregnant blue shark. He discovered a two-headed fetus inside the beast when he cut it up. After experts confirmed the discovery of a different two-headed bull shark fetus off the coast of Mexico, he decided to post the above photos.

That second encounter happened only a few years later, in 2013, around a year after the Deepwater Horizon oil catastrophe. When a crew of Florida fishermen grabbed a huge female bull shark in the Gulf of Mexico, they discovered that its uterus contained a two-headed fetus. While other shark species have been seen to be born with two heads, this was the first time the anomaly was observed in a bull shark.

A comprehensive research of two-headed blue sharks collected in the Gulf of California and off the coast of Mexico was published in 2011. Females of this species have the highest proportion of two-headed embryos because they bear the most offspring – up to fifty at a time.

In a recent laboratory investigation, Spanish researchers discovered a two-headed embryo in the eggs of an Atlantic sawtail catshark – the first time the aberration was seen in an egg-laying species. The study’s lead author, Valentn Sans-Coma, believes the deformation was produced by a genetic disease, despite the fact that the eggs were not exposed to illness, chemicals, or radiation.

There could be a variety of causes for the abundance of two-headed embryos in wild sharks. Overfishing-related viruses, metabolic diseases, pollution, and inbreeding may all play an impact.

Another recent study analyzed the two-headed fetuses of a houndshark and a blue shark, the first two-headed creatures to arise in Caribbean waters, by Nicolas Ehemann, an MA student at Mexico’s National Institute of Technology. Overfishing, and the accompanying reduction in genetic variety, he found, was the most likely source of the distortion.

On the other hand, Galván-Magaa, the author of the 2011 study, argues that there aren’t any more two-headed shark embryos, but that the media is covering them more. He claims to have seen a lot of strange things, such as a cyclops shark caught in Mexico a few years ago with a single, completely working eye at the front of his head. Such illnesses, however, can occur in all animal species, including humans.

Ehemann also concedes that shark malformations are difficult to study due to the scarcity of specimens. “It’s not like you can throw out the net a couple times and catch some double-headed sharks. “It’s just a coincidence,” the researcher explained. “I’d like to investigate these things, but it’s not like you throw out a net every now and then and get two-headed sharks,” he explains. “It’s haphazard.”

We can only hope that such occurrences are coincidental and that there is no underlying trend (or cause) of increased sightings.

Leave a Reply