The odd-looking sharks are hammerheads. The remainder of their bodies appear to be those of a typical shark, but their heads appear to have had their skulls seized by the eye sockets and stretched out sideways.

What benefits would having a head fashioned like a hammer have? And how did hammerhead sharks become what they are today?

I am a scientist who has spent over 30 years researching sharks. Even I was shocked by some of the replies to these queries.

Benefits of the hammer

According to scientists, there are three key benefits to sharks with hammer-shaped heads.

The first relates to vision. You could see far farther if your eyes were pointed in two opposing directions, like by your ears. You would be able to see more of your surroundings since each eye would see a distinct area of the globe. However, it would be challenging to estimate distances.

Hammerhead sharks have unique sensory organs called ampullae of Lorenzini dispersed over the underside of their hammer to make up for the trade-off. These pore-like structures are electrically sensitive.

The pores essentially function as a metal detector, detecting and finding prey on the ocean floor that is buried beneath sand. These sensory organs are present in regular sharks as well, but hammerheads have more. These sensory organs on a hammerhead’s stretched-out head can detect food more precisely the farther apart they are.

And finally, researchers believe that hammers let sharks to turn more quickly when swimming. You know how strong huge surfaces can be in motion if you’ve ever flown in an airplane or strolled in blustery weather with an umbrella. If you’re a hammerhead shark, you can turn more swiftly than other fish can to capture your intended supper if it swims past quickly.

The hammerhead family tree

It would be convenient if researchers like myself could examine fossils to chart the evolution of hammerhead sharks across time. Unfortunately, practically all of the hammerhead shark’s fossils contain its teeth. This is so because sharks have bonesless bodies. Your ears and nose are formed of cartilage, which is also what they are made of. Because cartilage decomposes far faster than teeth or bones do, it seldom becomes fossilized. Additionally, tooth fossils don’t provide any information regarding the development of hammerhead heads.

There are now nine different types of hammerhead sharks swimming around. Both their size and skull forms differ among them. Compared to their physique, some people have extraordinarily large heads. These include the Carolina hammerhead, the winghead shark (E. blochii), the big hammerhead (S. mokarran), the smooth hammerhead (S. zygaena), and the scalloped hammerhead (S. lewini) (S. gilberti).

Others, such as the scalloped bonnethead (S. tiburo), small-eye hammerhead (S. tudes), scoophead shark (S. media), and bonnethead (S. tiburo), have smaller hammers in comparison to their bodies (S. corona).

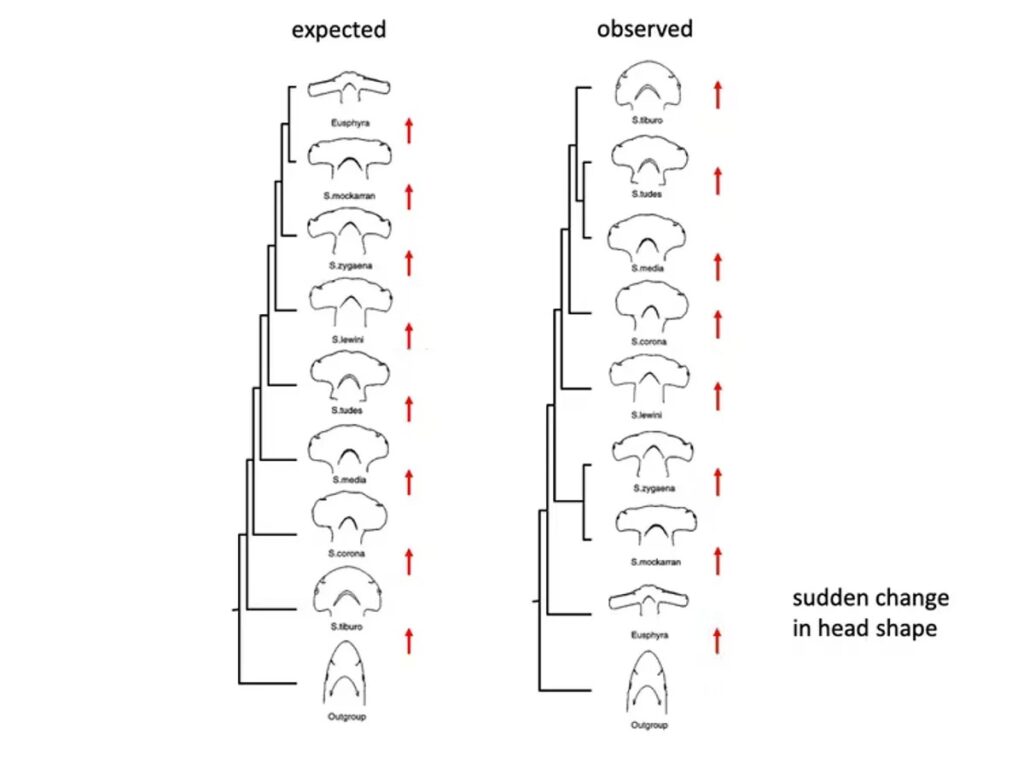

Long believed by scientists to have had a small hammer, certain hammers of hammerhead sharks gradually became larger over time. We believed that the various hammerhead shark species in existence today represented photographs from various stages of the evolutionary process, with the little hammerheads representing the earliest members of the family tree and the enormous hammerheads representing the most recent additions.

Since there are no remains to examine, researchers like me have looked at this concept utilizing DNA. The genetic substance called DNA is contained in cells and contains instructions on how a living thing will appear and behave. It may also be used to determine the relationships among living entities.

We utilized DNA to examine the connections between eight of the nine hammerhead species. We had no idea what to anticipate from the outcomes. The hammers of the older species were proportionately larger than those of the younger species.

Deformities as assets

When scientists consider evolution, we typically presume that living organisms change gradually, fine-tuning themselves to benefit from their surroundings. Natural selection is what we term this process. But as the development of hammerheads demonstrates, that isn’t necessarily how it goes.

An animal may occasionally be born with a genetic flaw that ends up being extremely beneficial to its survival. The characteristic can be handed on as long as the anomaly can coexist and the animal is able to reproduce. That’s exactly what occurred with hammerhead sharks, in our opinion.

The winghead shark (E. blochii), which has one of the broadest heads, is the hammerhead species that split off first. The size of the hammer has actually decreased through time due to natural selection. The bonnethead shark (S. tiburo), which has the tiniest hammer of all, turns out to be the most recent hammerhead species.

Gavin Naylor, Director of the University of Florida’s Florida Program for Shark Research.

Leave a Reply