In 1996, archaeologists in Gibraltar made a significant discovery in a cave: a human skull buried beneath layers of sediment containing fish, bird, and mammal bones, as well as carved flint objects. Recognizing the skull’s ancient origin, they embarked on a quest to ‘resurrect’ it.

At the time of its discovery, the humid climate of Gibraltar posed a challenge for DNA analysis, causing rapid deterioration of genetic material. Additionally, the skull was damaged, complicating efforts to study it further. DNA analysis was still in its early stages, making the extraction of viable genetic material unlikely.

Despite these challenges, scientists were determined to recreate the physiognomy of the woman they named Calpeia, after the classical term for Gibraltar, known in ancient times as Mons Calpe. Over the decades, the study of ancient DNA advanced significantly. In 2019, researchers at Harvard Medical School successfully extracted viable samples of ancient DNA from the 1996 skull, which was part of a genome analysis of 271 inhabitants of Spain, Gibraltar, and Portugal published in Science.

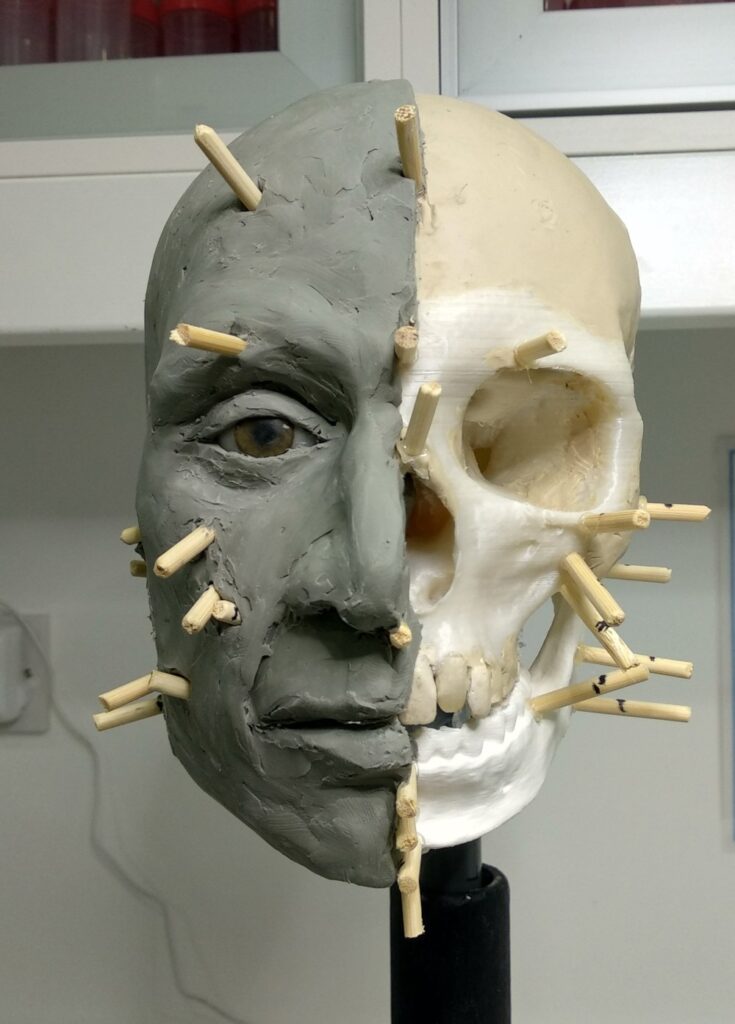

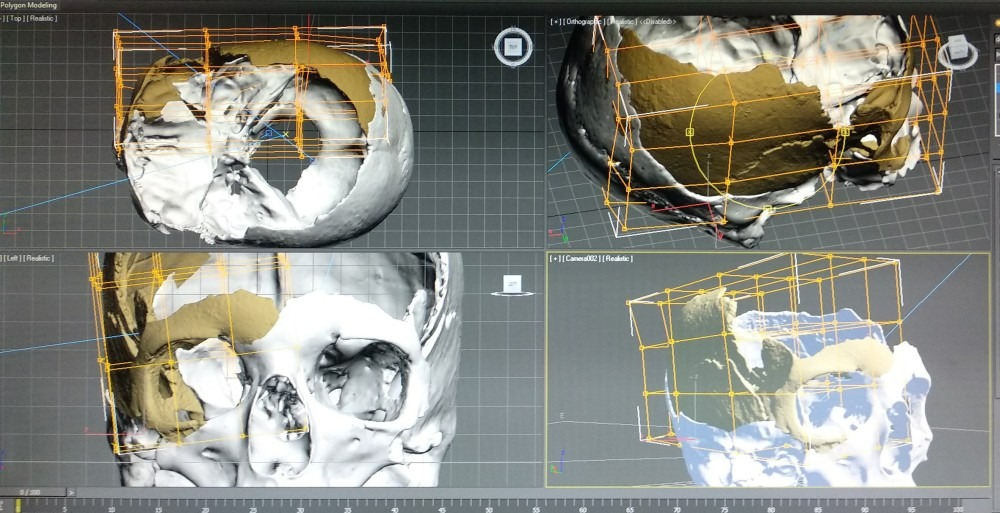

Following this breakthrough, the Gibraltar National Museum embarked on a forensic anatomical reconstruction of Calpeia’s face. The team scanned her broken bones and used 3D cloning and restitution programs to recreate missing and damaged portions, including her jaw. By combining data from the scans with genetic analysis results, they spent six months crafting a lifelike visage of Calpeia.

DNA analysis revealed that the skull belonged to a woman who lived around 5400 B.C., long after the Neanderthals of Gibraltar had become extinct. Calpeia was light-skinned, slightly built, and had dark hair and eyes. She was lactose intolerant, a common trait in her time, indicating that dairy farming was likely not part of her culture.

Living in the later Neolithic period, about 7,500 years ago, Calpeia’s era marked a shift from the hunter-gatherer lifestyle to agriculture and livestock raising across the Iberian Peninsula. While her exact age at death is indeterminable, cranial sutures suggest she was an adult between 25 and 40 years old. The skull’s deformation after burial required scientists to reshape a scanned copy to complete the missing areas.

The most exciting revelation came from the DNA analysis, which showed that only 10 percent of Calpeia’s genome came from the Iberian Peninsula population. The remaining 90 percent originated from Anatolia, modern-day Turkey, where Neolithic farmers had a high percentage of genes for dark eyes and light skin. In contrast, contemporary hunter-gatherers in central and western Europe exhibited genetic markers for dark skin and light eyes.

The high proportion of Anatolian genes in Calpeia’s DNA suggests her recent Anatolian origins, likely tracing back to her parents or recent ancestors who journeyed from Anatolia to Gibraltar by sea. A land journey would have taken years or generations, mixing her family’s DNA with local populations along the way, resulting in a more diverse genome.

Additional analyses of genes from individuals on the Mediterranean island of Sardinia also reveal a high proportion of Anatolian genes, supporting the theory of Anatolian exploration westward over the Mediterranean.

This ancient skull has indeed unveiled a wealth of historical and genetic information, offering a fascinating glimpse into the life and lineage of a 7,500-year-old Gibraltarian woman.

Leave a Reply