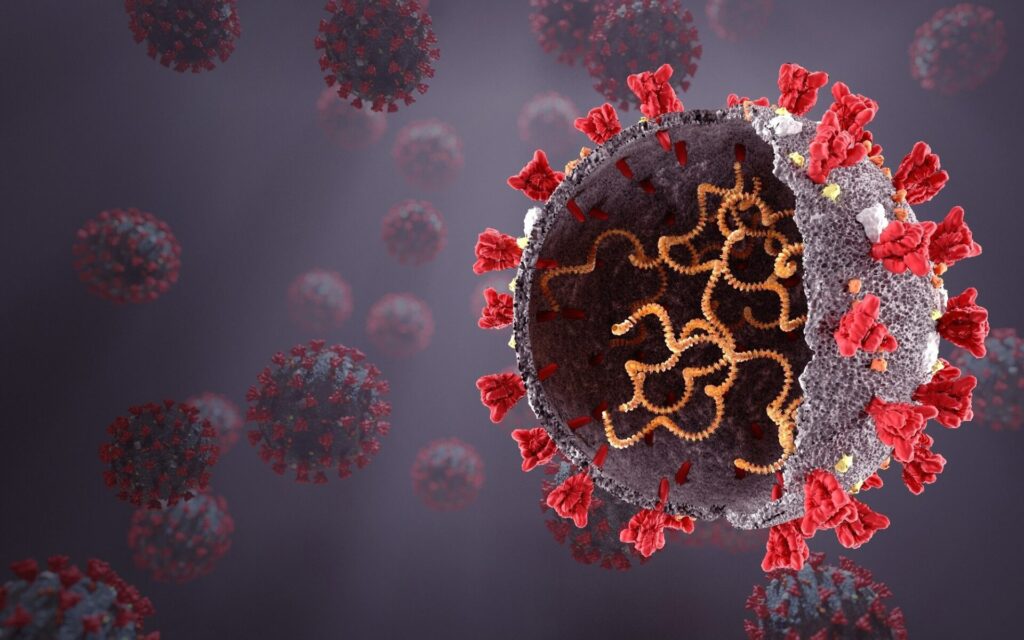

Look at you, over there, batting your spike proteins at me.

There’s a family of new COVID-19 variants in town, and at least one of them looks set to begin jostling for position at the top of the transmission stakes. They’ve been nicknamed the FLiRT variants, for reasons that will soon become clear. Here’s what we know about them so far.

If you’re thinking it’s been a long time since we had a new Greek letter COVID variant, you’re not wrong. The reason for that is pretty much all the variants currently circulating – as you can see in the latest data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) – are derived from the Omicron lineage, albeit quite distantly by now.

These latest variants to join the party are derivatives of JN.1, the variant that rose to global dominance at the start of this year and continues to account for a large proportion of cases.

As physician-scientist Eric Topol of The Scripps Research Institute explained in a recent edition of his newsletter, Ground Truths, the new variants have picked up mutations in their spike proteins. In one location, an amino acid labeled “F” was switched for one labeled “L”; in another, an “R” was swapped for a “T”. Put those letters together (with the judicious addition of an “i”) and you get FLiRT.

One of the FLiRT family, called the KP.2 variant, seems to be leading the pack at this point. CDC modeling suggests it could now be responsible for almost a quarter of infections. But is it anything to be concerned about?

Topol told Time that he’s not expecting a huge wave of infections from this variant: “It might be a ‘wavelet.’”

Some early data from researchers in Japan, which has been posted to preprint server bioRxiv and is yet to be peer-reviewed, supports this. The authors wrote that “the infectivity of KP.2 is significantly (10.5-fold) lower than that of JN.1,” based on experiments in which they tried to infect cells with pseudoviruses, particles of other viruses that had been modified to carry the different COVID spike proteins.

Despite this decreased infectivity, however, the study authors also found that KP.2 was able to spread more easily than JN.1, and may also be more resistant to immune responses from vaccines and prior infections.

Again, this data has not yet been published in a peer-reviewed journal. But it’s still something health authorities will want to keep a close eye on, especially because it’s probably been a while since most people had a COVID-19 booster – if they bothered to get one at all.

The World Health Organization released a statement recently, recommending that future COVID-19 vaccine formulations specifically target JN.1 and its derivatives. They accept that “the timing, specific mutations and antigenic characteristics, and the potential public health impact of newly emerged (e.g. KP.2) and future variants remain unknown,” but based on the current data they believe that setting our sights on JN.1 is the best bet.

But vaccines only work if people take them. Just this week, a new study published in Nature Medicine reports that trust in vaccines remains a mixed picture in the wake of this pandemic.

“While we are concerned about the evident fallout of the pandemic on large numbers of people, we still see a general openness to immunization that we must build on to boost vaccine confidence, including acceptance of new generations of COVID-19 vaccines and boosters,” senior author Ayman El-Mohandes said in a statement. “We must design targeted messages from trusted communicators to encourage vaccine uptake.”

Leave a Reply