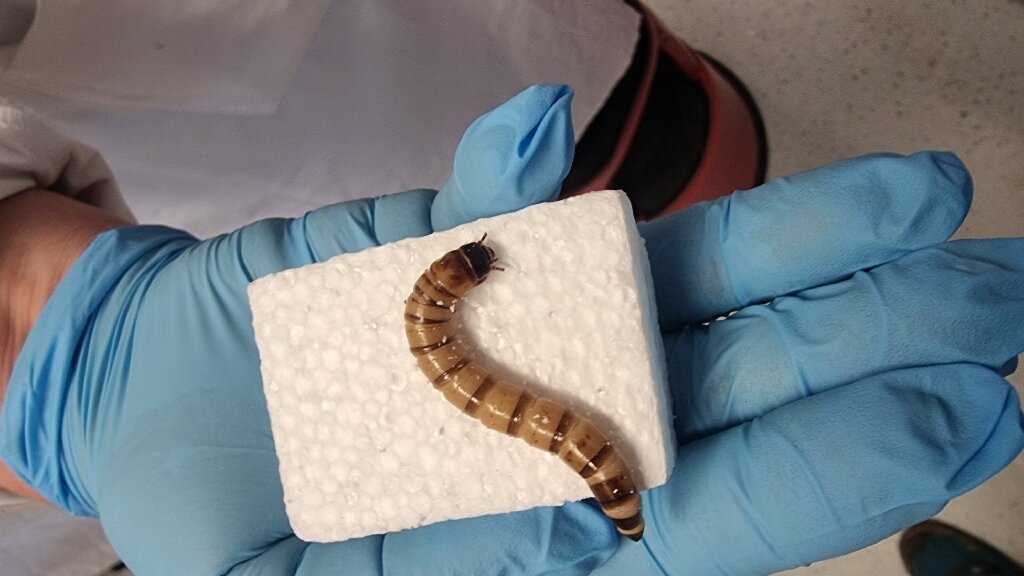

In a surprising turn of events, superworms, commonly known as wiggly bugs often sold as lizard food, have revealed a remarkable ability to digest polystyrene, offering a potential breakthrough in addressing the planet’s persistent plastic problem. Scientists from the University of Queensland in Australia, as reported in the journal Microbial Genomics, have unveiled that the Zophobas morio “superworms” possess a bacterial enzyme in their gut that enables them to happily consume polystyrene.

The study, led by Dr. Chris Rinke from UQ’s School of Chemistry and Molecular Biosciences, discovered that superworms fed a diet exclusively consisting of polystyrene not only demonstrated the ability to consume the human-made plastic but also gained a little weight in the process. This unexpected finding suggests that superworms might thrive on a diet primarily composed of polystyrene.

Dr. Rinke clarified that superworms, technically the larvae of the darkling beetle Zophobas morio, have a history of damaging and consuming plastic. Their larger size, compared to other insect larvae in the same family, hinted at the possibility of their enhanced capability to digest plastic, a hypothesis that the study confirmed.

While previous studies hinted at the superworms’ plastic-eating proclivities, the latest research delved deeper into the genetic underpinnings of this unique talent. Sequencing the DNA of the microbes inhabiting the superworm gut allowed scientists to identify the bacterial genes responsible for producing plastic-degrading enzymes. This genetic insight could pave the way for screening other bacteria with similar plastic-degrading enzymes, potentially expanding the scope of this plastic-eating ability.

Dr. Rinke envisions a scalable solution to plastic disposal, emphasizing the use of bacterial enzymes over employing tanks filled with hungry superworms. The proposed method involves collecting polystyrene waste, mechanically shredding it similar to the superworms’ process, and degrading it in bioreactors with a combination of plastic-munching enzymes. The resulting chemical compounds could then be utilized by other microbes to synthesize higher-value products, such as bioplastics like PHA.

While the realization of this vision remains uncertain, the discovery underscores the potential of harnessing nature’s solutions to combat plastic pollution. The collaboration between science and the inherent abilities of these “creepy crawlies” showcases a promising avenue in the ongoing battle against plastic waste.

Leave a Reply