The demise of Gigantopithecus some 100,000 years ago reveals why big is often not better.

Sometimes, in evolution, the bigger they are, the harder they fall.

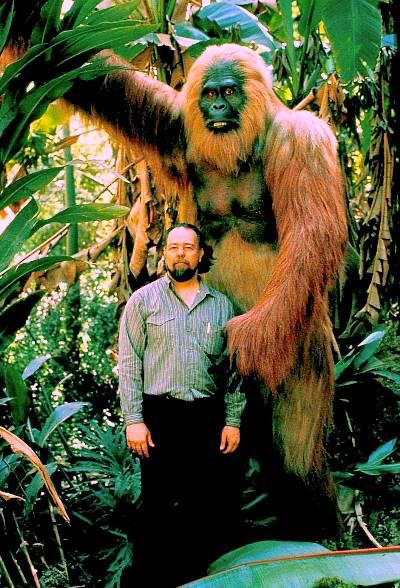

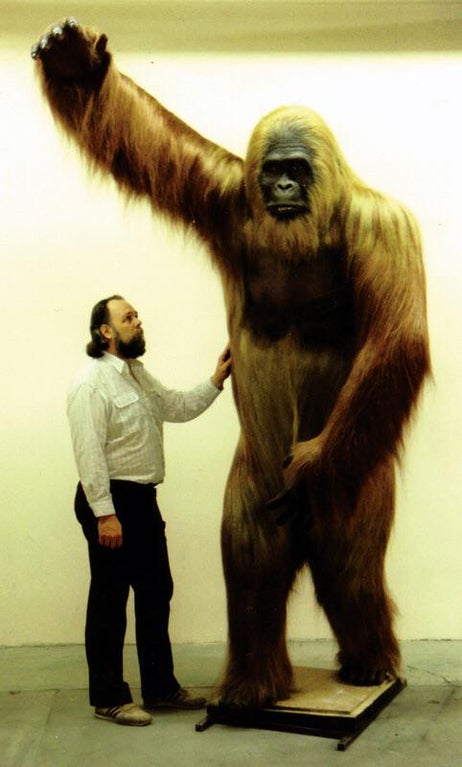

And Gigantopithecus was pretty darn big. Fossils indicate it stood as high as 10 feet (3 meters) and weighed up to 1,100 pounds (500 kilograms)

If you’re an animal, there are advantages to being gigantic. You’re less vulnerable to predators, and you’re able to cover a lot of territory when looking for food. Gigantopithecus thrived in the tropical forests of what is now southern China for six to nine million years.

But around 100,000 years ago, at the beginning of the last of the Pleistocene ice ages, it went extinct—because in the changed climate its size had become a fatal handicap, a new study suggests.

“Due to its size, Gigantopithecus presumably depended on a large amount of food,” explained Herve Bocherens, a researcher at Tübingen University in Germany, in a press statement. “When, during the Pleistocene, more and more forested areas turned into savanna landscapes, there was simply an insufficient food supply for the giant ape.”

Gigantopithecus, a fruit-eater, failed to adapt to the grass, roots, and leaves that became the dominant food sources in its new environment. Had it been less gigantic, it might have endured somehow. “Relatives of the giant ape, such as the orangutan, have been able to survive despite their specialization on a certain habitat,” said Bocherens, because they have “a slow metabolism and are able to survive on limited food.”

The rise and fall of Gigantopithecus illustrates why, over time, size can yield diminishing returns. “There are short-term advantages that come with being bigger, but it also brings long-term risk,” says Aaron Clauset, a computer scientist at the University of Boulder, who has studied the body sizes of thousands of species spanning two million years of the fossil record.

It’s not just that a bigger body requires more food, says Clauset. It’s that “as you get bigger, you tend to have fewer children. That means your population tends to be smaller and more sensitive to fluctuations.”

As a result, changes in weather or climate that threaten a food source can reduce a large-bodied species’ numbers to the point of “demographic death.”

In fact, Clauset found that extinction rates increase as a species gets larger in size. That’s why goliaths such as Gigantopithecus and the giant sloth no longer roam the Earth. Every animal species has an effective upper limit on how big it can become; how close it can get to the edge of the precipice before toppling off into oblivion.

At least that’s the case for mammals—dinosaurs were a different story, Clauset acknowledges. Until an asteroid plunged them into armageddon, they were both enormous and successful for tens of millions of years. Why couldn’t Gigantopithecus do that? “It may be that mammals have higher metabolic needs, converting more of their energy intake into heat, because they’re warm-blooded,” Clauset says.

Leave a Reply