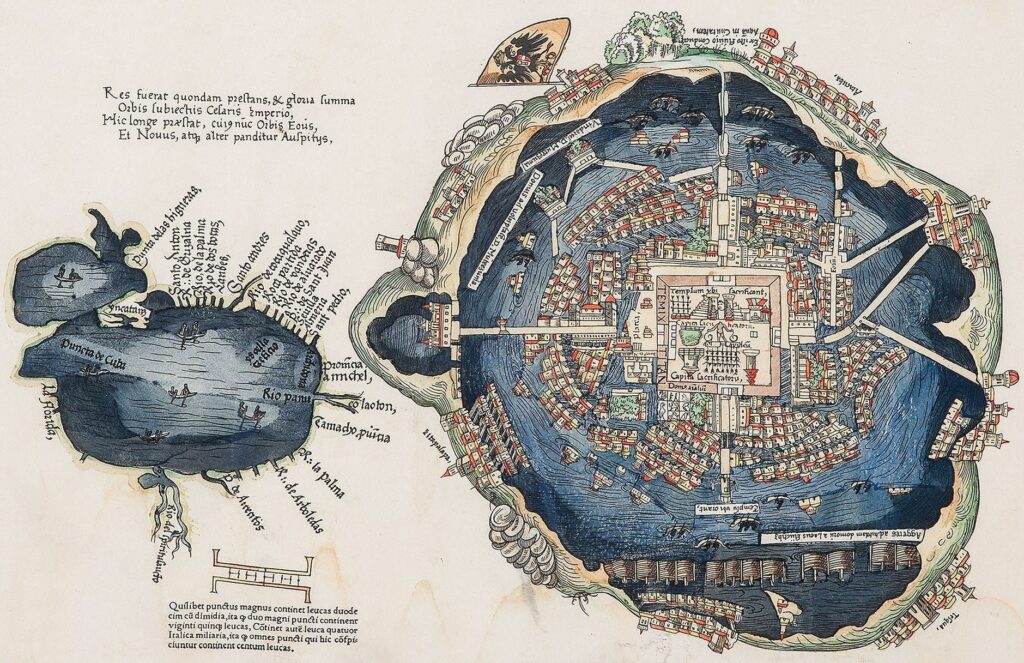

Throughout the annals of history, maps have always played a critical role in revealing the mysteries of the world to mankind. In this context, the first European map of Tenochtitlan, the capital of the Aztec Empire, holds a significant position. This map, drawn in 1524, is a milestone not only in the history of cartography but also in the confluence of two contrasting civilizations: the indigenous peoples of Mesoamerica and the European explorers.

THE FALL OF TENOCHTITLAN

In 1521, Hernán Cortés, leading the Spanish conquistadors, succeeded in overthrowing the last emperor of the Aztecs, Cuauhtémoc, marking the fall of the mighty Aztec empire. Tenochtitlan, the empire’s sprawling capital located on an island in Lake Texcoco in present-day Mexico City, was virtually decimated. Despite the destruction, the city’s elaborate system of canals, temples, causeways, and marketplaces captivated the Spaniards.

CRAFTING THE MAP

With a desire to document this unique city and its intricate urban layout, a map was commissioned. It was to be a testimony to the magnificence of the fallen city and serve as a valuable resource for the new rulers. The task fell upon an indigenous group of artists and scribes who had formerly worked for the Aztec elites. They were fluent in both the indigenous Nahuatl language and Spanish and skilled in the European and Mesoamerican cartographic traditions.

The map they created was a blend of European and Aztec cartographic styles. On the one hand, it adhered to the European tradition of creating bird’s-eye view cityscapes. On the other hand, it incorporated indigenous symbols and color coding, similar to the pictorial manuscripts known as codices used by the Aztecs to record their history and religious beliefs.

UNVEILING THE AZTEC CAPITAL

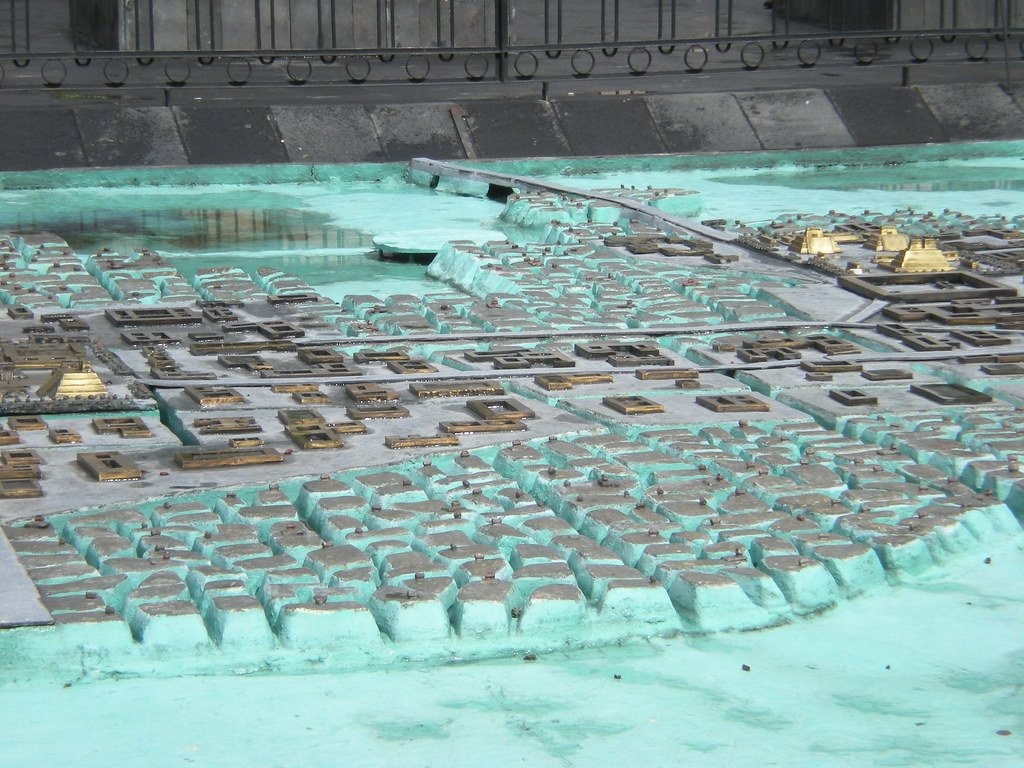

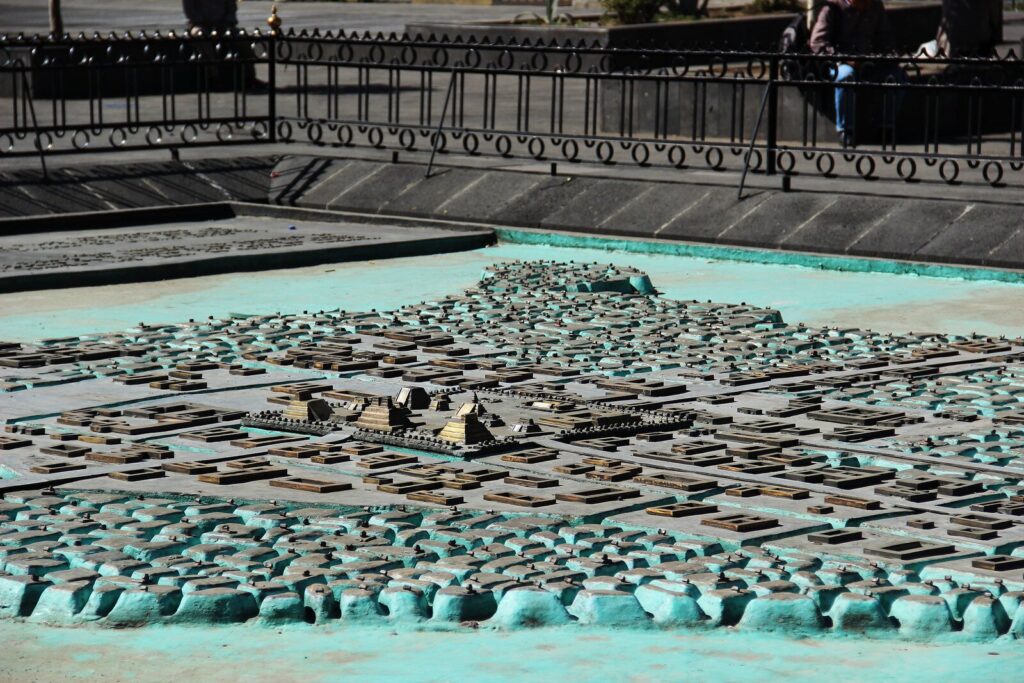

The map of Tenochtitlan is a testament to the city’s grandeur and the Aztecs’ advanced urban planning. The city, divided into four zones, was depicted with its complex network of canals, which served as streets for their canoe traffic. Iconic landmarks like the Templo Mayor, the royal palace, and the bustling marketplace of Tlatelolco were illustrated with careful detail.

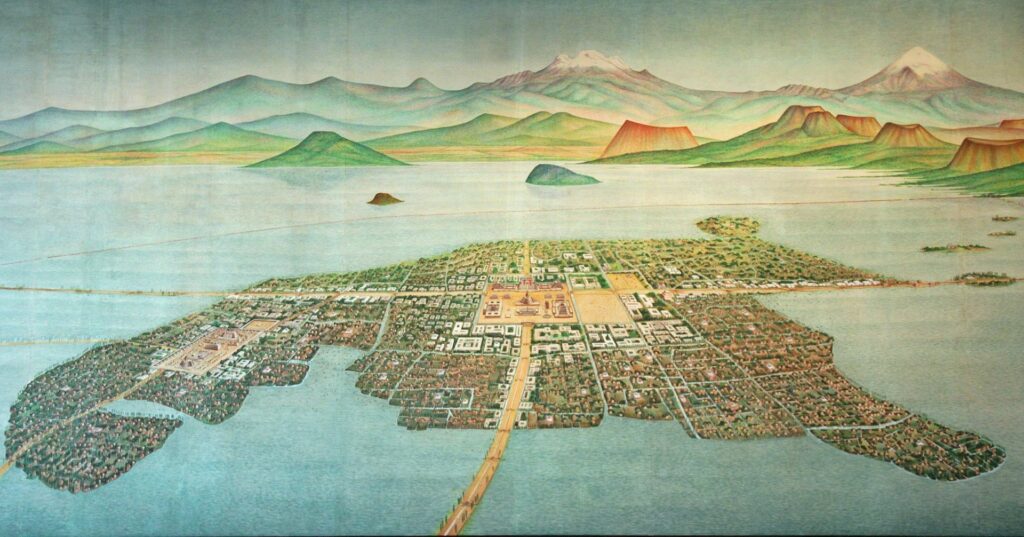

Moreover, the map revealed the city’s relationship with its environment. Tenochtitlan was surrounded by Lake Texcoco and connected to the mainland by three causeways. These causeways and the aqueduct that brought fresh water from the mainland were carefully depicted.

TENOCHTITLAN: THE VENICE OF THE NEW WORLD

Tenochtitlan was a large city-state located on an island in Lake Texcoco, in the Valley of Mexico. Founded in 1325, it rapidly grew to become the capital of the expansive Aztec Empire. At its peak, the city had a population of between 200,000 and 250,000 people, making it one of the largest cities in the world at that time.

The city was designed around a ceremonial center, where important political and religious buildings were situated. The most prominent of these was the Templo Mayor, a large pyramid dedicated to the gods Huitzilopochtli and Tlaloc. Surrounding the ceremonial center were four main districts, or ‘campan’, which were divided into 20 precincts (‘calpullis’).

A sophisticated system of canals ran through the city, enabling transport by canoe. Large causeways connected Tenochtitlan to the mainland, which was a marvel of engineering at the time. The city was also notable for its public buildings and marketplaces. The largest marketplace was in the nearby city of Tlatelolco, which was eventually absorbed into Tenochtitlan.

The economy of Tenochtitlan was based on agriculture, trade, and tribute from conquered territories. The Aztecs employed a system of agriculture known as ‘chinampas’, or floating gardens, which were small, rectangular areas set upon the shallow lake bed. They grew various crops, most notably maize, beans, squash, and chili peppers.

Trade was carried out at a local, regional, and long-distance level, with goods from as far away as Central America and the American Southwest reaching Tenochtitlan. The city’s grand marketplaces were filled with goods such as textiles, pottery, food, precious stones and metals, feathers, and other items.

Tenochtitlan was the center of Aztec civilization, which was rich in mythology and religious traditions. Society was stratified, with nobles, priests, warriors, traders, artisans, farmers, and slaves each having their place. The Aztecs had a complex system of education, with separate schools for the nobles (calmecac) and the commoners (telpochcalli).

The ruins of the Templo Mayor were rediscovered in the 20th century, and today they provide an important archaeological site in the heart of Mexico City. The rich history of Tenochtitlan continues to influence modern Mexican culture and is a potent symbol of the country’s indigenous heritage.

AFTERMATH AND IMPACT

The map was sent to Charles V, the Holy Roman Emperor, in 1524. The map provided Europe with its first visual representation of the New World’s urban complexity, shifting perceptions about the so-called “primitive” societies of the Americas. It served as a tool for the Spanish administration to better understand and govern their newly acquired territory.

Yet this map was not merely a practical tool; it became an emblem of conquest, a symbol of European domination over the New World. By asserting European spatial understanding over an indigenous landscape, the map participated in a broader colonial project of control and appropriation.

Nevertheless, the enduring legacy of this map lies in its syncretic character. It serves as a tangible symbol of a moment of profound cultural encounter, blending European and Aztec conventions to create a document that both records and transcends its historical moment.

To this day, the 1524 map of Tenochtitlan continues to fascinate scholars and the general public alike. As a window into a lost world, it speaks volumes about the richness of Aztec civilization and the early days of intercultural contact in the New World.

Leave a Reply