Studies have found that thanks to their genetic mutations, the Sherpa people, who have been living in the high altitudes of the Himalayas for centuries, have developed ‘superhuman’ qualities as mountain climbers.

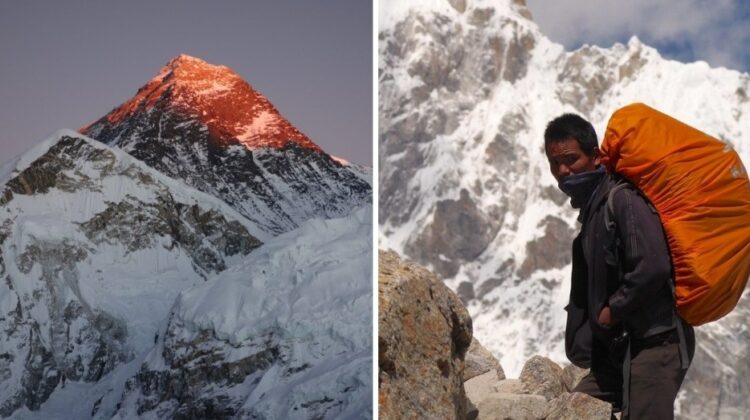

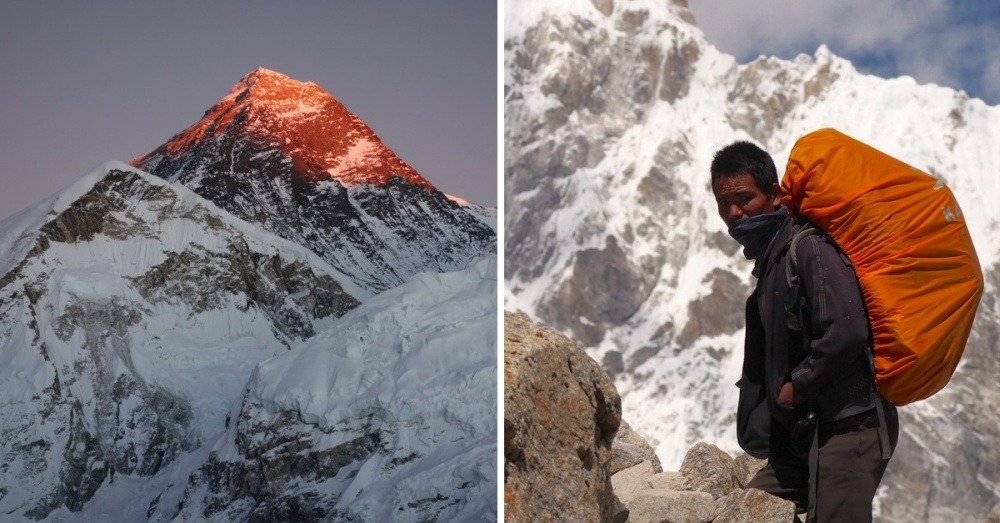

The Sherpa are a Nepali ethnic group who migrated to the mountainous regions of Nepal 500 years ago from Tibet. Today, they are well-known for being among the best mountaineers on the planet, and holding many records in mountain climbing. Sherpas are also the ones who secure ropes on climbing routes, and help guide Westerners who want to climb Mount Everest.

But it wasn’t always like that. Before the 1920s, the Sherpa made a living from high-altitude farming, herding cattle, and wool spinning. They did pass by the peaks of the Himalayas but didn’t climb them, as they believed them to be the home of the gods. When the British first started planning mountain climbing expeditions to the Himalayas, they hired the Sherpa as porters. From then on, mountain climbing became a significant part of Sherpa culture. Due to their willingness to guide Western mountaineers, and the ability to climb the tallest peaks, the help of the Sherpa contributed greatly to the expedition efforts of the Himalayas.

The first major breakthrough was the first ascent of Mount Everest in 1953. A mountaineer from New Zealand, Edmund Hillary, and one of the most famous Sherpas, Tenzing Norgay, became the first people known to have climbed the 29,028 foot (8,848 meters) high summit of Mount Everest on 29 May 1953.

After the successful attempt of Hillary and Norgay, foreign climbers flocked to the Sherpa homeland, wanting to repeat the achievement of climbing the world’s tallest mountain. As the new interest in climbing grew gradually over the years, so did the number of Sherpa guides hired by Western climbers and tourists who also wanted a piece of Mount Everest. Thus began the age of commercial mountaineering and guiding. At the dawn of mountain climbing, only the most experienced mountaineers could attempt summiting the giants of the Himalayas. Today, any reasonably fit person can get a shot at Everest by commercial agencies (albeit it costs a small fortune).

The once isolated community now totally revolves around mountain climbing, and it has steadily professionalized the Sherpa. While the mountain climbing industry has made them one of the richest ethnicities in Nepal, their mountaineering achievements are also very impressive. Sadly, these achievements are often less acknowledged by the Western mountain climbing community and media.

Besides Tenzing Norgay, famous Sherpas include mountain guide Kami Rita Sherpa, who holds the world record for the number of successful ascents of Mount Everest, with a stunning 25 times; Pasang Lhamu Sherpa, the first Nepali woman to reach the summit of Everest, inspiring a generation of women in Nepal; her namesake, Pasang Lhamu Sherpa Akita, Maya Sherpa, and Dawa Yangzum Sherpa, who became the first Nepali women to climb K2, the world’s most dangerous (1 out of 4 climbers die on K2) and second highest mountain; and Apa Sherpa, nicknamed ‘Super Sherpa’, who held the most number of Everest ascents for a long time before retiring. He raises awareness of climate change in the Himalayas, and during his climbs, he removed 29 762 lb (13 500 kilograms) of waste from Everest, including 992 lb (450 kilograms) of human waste and corpses of mountaineers whose families had requested they be brought back.

It’s also important to mention Nirmal “Nims” Purja, and Sherpas Mingma Gyabu Sherpa, Lakpa Dendi, Geljen Sherpa, and Gesman Tamang, who summited all 14 of the 8000ers in 6 months and 6 days, shattering previous world records in the process, and representing the Nepali climbing community.

Scientists have long been interested in how the Sherpa can cope with high altitude atmospheres where oxygen is much more scarce. Previous studies have indicated that there are differences between the Sherpa and ‘lowlanders’, pointing to fewer number of red blood cells in Sherpas at altitude, but also a higher level of nitric oxide, which helps the blood flow.

To get to the bottom of the superhuman climbing abilities of the Sherpa, as part of the Xtreme Everest project, a team of researchers followed a group of mostly European researchers and 15 Sherpas as they made an ascent to Everest Base Camp, so their response to the high-altitude could be compared.

The researchers took samples from blood and muscle biopsies; first in London, then again upon arrival at Base Camp, and for a final time after spending two months at Base Camp. These samples were then compared with samples from the Sherpas. It’s important to note that the Sherpas who participated in the study weren’t elite high altitude climbers, and live in lower areas of the Himalaya. Their baseline measurements were taken in the capital of Nepal, Kathmandu.

The study, published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, found that even at baseline measurements, the bodies of the Sherpas were more efficient at producing ATP, the energy that powers the human body. They have also found lower levels of fat oxidation in the Sherpas, meaning that their tissues were able to make much better use of oxygen, and generate energy more efficiently.

The different measurements taken at altitude didn’t really change from baseline samples in the Sherpas, while the measurements of lowlanders changed after spending time at higher altitudes. Furthermore, another major difference was in the level of phosphocreatine between the two groups. Phosphocreatine helps muscles contract when there isn’t any ATP in the body. Interestingly, the levels of phosphocreatine in the lowlanders have crashed after 2 months, while the levels of the Sherpa people have, in fact, increased. These findings suggest that the Sherpas were born with a more advantageous genetic mutation that gave them a unique metabolism.

This project could also improve outcomes for those who are in ICUs by understanding why some people in emergency situations suffer from oxygen deficiency (hypoxia) far more than others. Eventually, this could lead to finding more effective treatments for those who are at the greatest risk.

Leave a Reply