A tiny’mechanical’ bug once assisted professionals in getting their brains into gear… literally! While the natural and mechanical worlds appear to be diametrically opposed, the ‘Issus coleoptratus,’ also known as a nymph insect, demonstrated that they are in fact inextricably intertwined.

This little organism, which grows up to 0.28 inches and is ubiquitous throughout Europe and North Africa, was revealed to have an amazing organic propulsion mechanism in 2013. According to a paper published in Science, the Issus’ skeleton included gears in its hind legs.

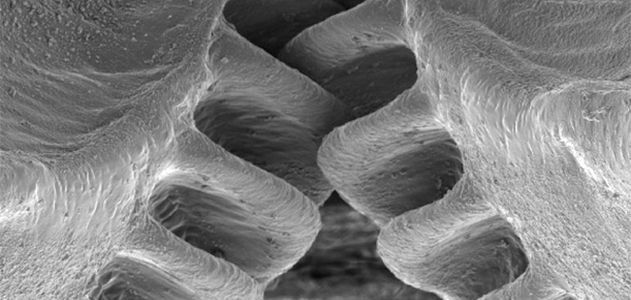

According to their news release on EurekAlert, authors and scientists Malcolm Burrows and Gregory Sutton noticed “hind-leg joints with curving cog-like strips of opposing ‘teeth’ that intermesh, turning like mechanical gears to coordinate the animal’s legs when it launches into a jump.” Their discoveries represent the “first discovery of mechanical gearing in a biological structure.”

This would have come as a surprise to the Greek mechanics of Alexandria, who are credited with inventing the mechanical gear about 300 B.C.E. Mother Nature had them licked from the start.

Burrows and Sutton arrived to this result using a mixture of high-speed footage and experimentation using deceased Issus. The video provided them with a close-up view of the insects in action. Meanwhile, electrical stimulation of one leg caused it to stretch, activating the second leg and demonstrating how the gears function together.

The insect’s inner workings, according to the announcement, “exhibit amazing engineering similarities to those found on every bicycle and within every automobile gear-box.” Not only that, but the design is also rather complex. “At the place where it links to the gear strip, each gear tooth has a rounded corner; a characteristic identical to man-made gears such as bike gears – essentially a shock-absorbing device to prevent teeth from shearing off.”

Issus coleoptratus does not just jump from plant to plant using its gears. It requires the mechanism to stay on track. “To jump, both of the insect’s rear legs must push forward at the same moment,” Smithsonian.com adds. “Because they both swing laterally, extending one a fraction of a second earlier than the other would throw the insect off course to the right or left instead of straight forward.” This makes the small insect a fantastic jumper.

The breakdown nearly reads like an engine manual: According to the news announcement, “each gear strip in the juvenile Issus was roughly 400 micrometres long and contained between 10 to 12 teeth, with both sides of the gear in each leg holding the same number – giving a gearing ratio of 1:1.”

However, the insect varies from a simple machine in several ways. “Unlike man-made gears, each gear tooth is asymmetrical and bent towards the place where the cogs interlock – because man-made gears require a symmetric design to operate in both rotating directions, but the Issus gears only push the animal ahead in one direction.”

One perplexing trait is that the gears appear only in the juvenile/nymph stage. When the Issus is completely developed, it replaces the previous system with what Science calls a “high-performance friction-based mechanism.” It is believed that once the insect reaches adulthood, it will be unable to regrow any damaged gears caused by the molting process.

This is “when animals shed stiff skin at critical stages of development in order to expand.” Molting cures any damage, so when the process ends, nature provides a more enduring remedy.

The Issus isn’t the only one who has what amounts to a built-in machine. A cog wheel turtle, for example, gets its name from the gear visible on its shell. However, other from being ornamental, this serves no useful purpose. No doubt, speculation over how the old animal kingdom was fueled will continue.

Meanwhile, the Issus is a fantastic example of how mechanics is as much about blood and guts as it is about oil and grease.

Leave a Reply