There are two ideas that could help preserve the Arctic and buy us time.

The Arctic is warming four times faster than the rest of the world, and in some places up to seven times faster. According to new research conducted by a group of Norwegian experts. This phenomenon, known as “Arctic amplification,” is well recognized, but according to the latest study, the region is warming faster than previously assumed.

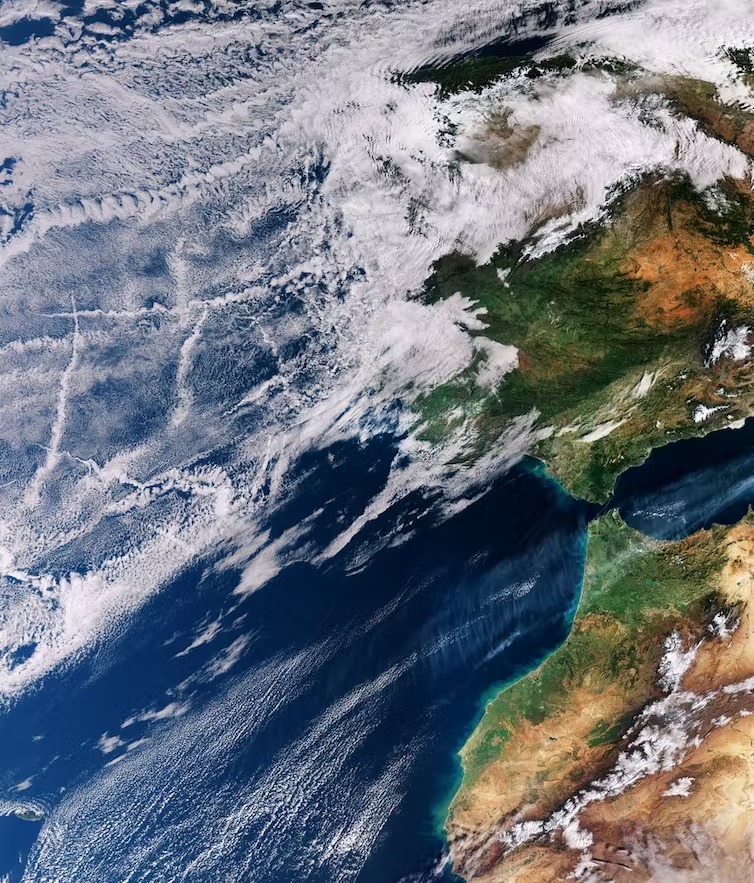

One of the reasons for this is the disappearance of Arctic sea ice. Exposed ocean water absorbs more solar radiation than white ice. As the ice cover recedes, the rate of warming accelerates. This is what climate scientists refer to as a positive feedback loop, often known as a tipping point.

Changes in the Arctic can have tremendous and far-reaching consequences for the rest of the planet. Greenland’s melting ice sheet, for example, might boost sea levels, while ocean circulation currents can shift, affecting weather patterns elsewhere.

The obvious question then is whether we can halt the warming, particularly in the Arctic. Fortunately, there are various paths we can take, even though they are all untested in practice.

Fill the skies with tiny particles

The first approach would be to inject sulphur dioxide into the stratosphere, causing microscopic particles to develop and reflect more of the sun’s energy back into space. The ground below would cool as less solar radiation entered the lower layers of the atmosphere. This is referred to as stratospheric aerosol injection.

The topic has long been investigated and is similar to what happens when a major volcano explodes. For example, the 1991 eruption of Mount Pinatubo in the Philippines emitted over 20 million tonnes of sulfur dioxide and ash particles, cooling the earth by approximately 0.5°C for a year (for context, that temporarily erased about half of the global warming since pre-industrial times).

This method of cooling the Earth would include injecting sulphur dioxide into the stratosphere at low latitudes. The material would then be spread throughout the earth by winds, eventually migrating to the pole of the hemisphere into which it was discharged, producing a reflecting shield. If the emission was directed at low latitudes in both hemispheres, it would cool the entire planet.

If we only wanted to cool the Arctic, the particles could be released closer to the region. The stratosphere also begins much lower down (approximately 9km at the North Pole versus 17km at the equator), reducing the need for planes to go so high.

Brighten the clouds

The second concept entails “brightening” clouds above the ocean to reflect more of the sun’s energy back into space. This is based on the fact that particles expelled from ship funnels induce clouds to form over the ocean under certain conditions.

There is enough of dust and other microscopic particles over land for clouds to develop around, but there is far less over the ocean. Clouds that do form over the water tend to form around salt crystals left behind after “sea spray” droplets evaporate in the air.

The size of the salt crystals, however, determines the type of clouds that form. If the crystals are small enough, clouds are created of many little droplets. This is significant because clouds made up of smaller droplets appear whiter than clouds made up of larger droplets and hence reflect more sunlight, even if the clouds contain the same total amount of water. As a result, it may be able to whiten clouds by producing more sea spray and tiny droplets. This might be accomplished near the Arctic by deploying boats equipped with pumps and nozzles.

So, there are two solutions that could help protect the Arctic and buy us time while we work tirelessly to address the main cause of the problem, which is that the level of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere is already too high, and we are already making matters worse.

However, each of these proposals for preventing Arctic warming require much more focused research and development. This work must include worldwide groups, particularly those most affected by climate change and least equipped to adapt. This includes indigenous populations not only in the Arctic, but also in other parts of the world, where governments may cease to exist in the future decades due to rising sea levels.

Hugh Hunt, Reader in Engineering Dynamics and Vibration, University of Cambridge, and Shaun Fitzgerald, Director, Centre for Climate Repair, University of Cambridge

Leave a Reply