Journey back in time to the heart of Andalusia, Spain, where a 5,000-year-old marvel, the Dolmen of Soto, beckons with its enigmatic whispers from the past.

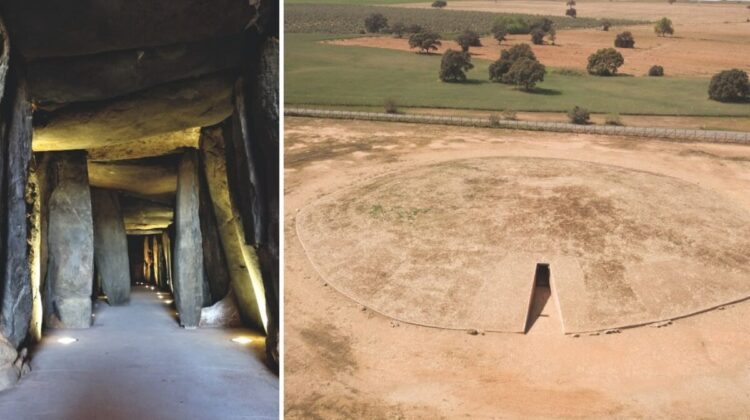

In for an adventure to a fascinating and mysterious Neolithic site in Spain? If you are, then you should definitely consider a visit to the Dolmen of Soto, a subterranean structure in Trigueros, Andalusia, Spain. Also known as the ‘Underground Stonehenge’, this impressive monument, built between 4,500 and 5,000 years ago, is one of about 200 ritual burial sites in the province of Huelva.

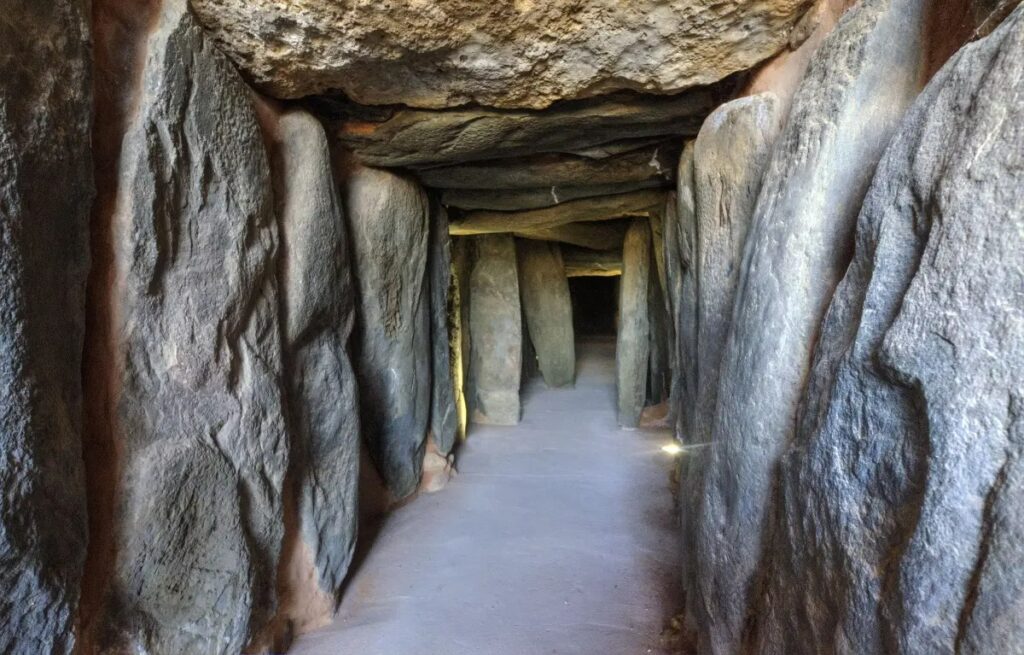

The dolmen consists of a circular mound with a long passage that leads to a chamber, where eight human remains were found along with various artifacts including cups, bowls, plates, daggers, and marine fossils – all essential for the afterlife. But what makes this dolmen truly unique is the presence of engravings and paintings on some of the standing stones that line the passage and the chamber. These images depict humans, cups, knives, and geometric forms, and reveal a glimpse into the beliefs and practices of the people who built and used this tomb.

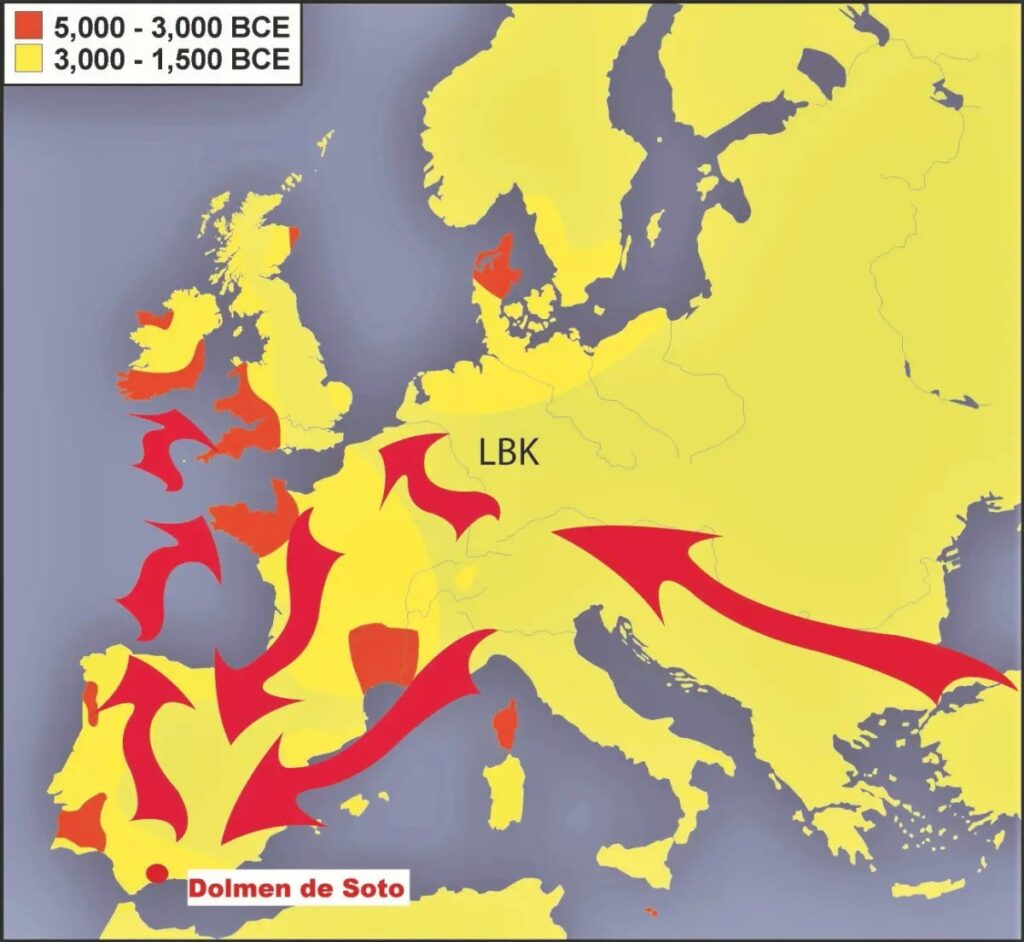

The origins of Neolithic tomb construction in Europe remain elusive. The Neolithic Revolution began around 10,000 BC in the Middle East’s ‘Fertile Crescent,’ but the development and spread of tomb architecture in Europe are less clear.

By the 5th and 4th millennia BC, passage graves became prominent, likely originating from an earlier tomb style in eastern Europe. This passage-grave tradition likely started in the Iberian Peninsula before spreading northward to areas of Atlantic Europe.

The passage-grave tradition in the Iberian Peninsula likely began in the 4th millennium BC, influenced by ideas related to celestial or life/death cycles. These tombs served as a means to honor the deceased and possibly signify one’s status within the community based on degree of access to the burial site.

This architectural movement, along with varying burial practices and grave goods, gained popularity for at least two millennia, evolving in terms of styles, size, and use during its development.

Dolmen de Soto was discovered in 1923 by Armando de Soto Morillas, who wanted to build a new house on his estate. He soon realized that he had stumbled upon an ancient site and contacted the German archaeologist Hugo Obermaier, who excavated and documented the dolmen between 1924 and 1926.

While the region of Andalusia houses approximately 1,650 such Neolithic burial monuments (with the province of Huelva alone boasting around 210), the Dolmen of Soto is unique as it stands in isolation, distinct from the clustered architectural styles of others.

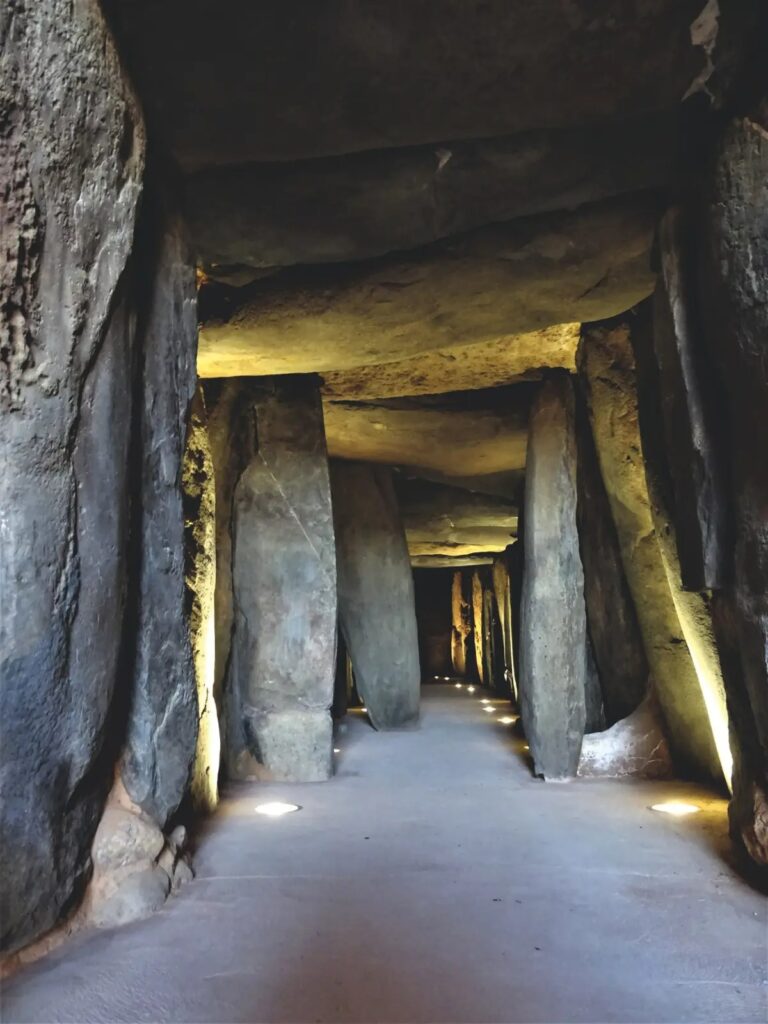

Looking at these tombs from the outside, a typical feature of a passage grave is a circular mound with an east-west-oriented entrance leading to an underground corridor. This corridor, known as the passage, usually connects to a designated burial chamber

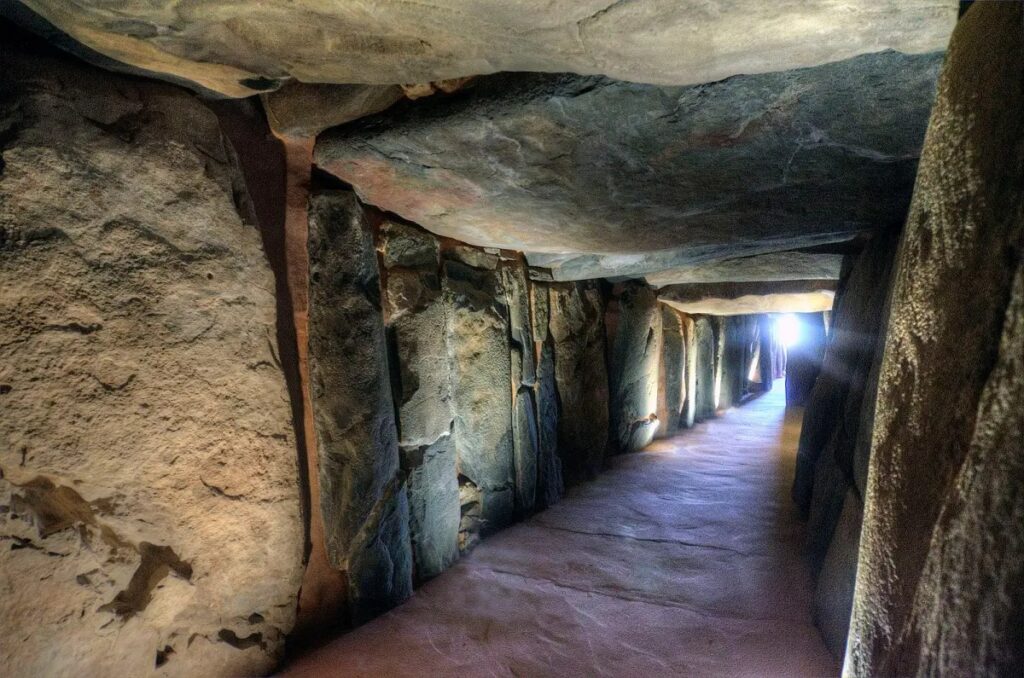

In the Dolmen de Soto, the passage and chamber create a continuous gallery that narrows midway. Stone uprights within the passage and chamber were engraved with megalithic art, often accompanied by painted schematic images. This artwork may have been created during construction or, more likely, while the tomb was in use.

In recent years, a team of researchers from Portugal, Spain, and Britain undertook a comprehensive study of the engraved and painted stones within the dolmen. They used various techniques, such as Raman spectroscopy, to record and analyze the images, which had been largely overlooked by previous scholars.

Over 60% of the monument’s uprights contained engravings and pigment traces, which were illuminated using photogrammetric techniques. The art includes various motifs, such as circles, daggers, human figures, cupmarks, geometrics, and circular patterns, providing insights into the Neolithic society’s changes, particularly in the context of the introduction and use of copper and bronze weaponry.

The team found that some of the engravings were made by reusing an older menhir, while others were created during or after the construction of the dolmen. They also discovered that some of the paintings were made with red ochre, which was used as a pigment throughout prehistory.

The researchers suggest that the images might have had different meanings and functions depending on their location, orientation, and visibility within the dolmen. The presence of red pigments applied to the engravings suggests an intentional act to enhance the visibility of some motifs.

The team is now trying to determine whether this act merely served as visual enhancement or whether the paint added to the potency to the engravings.

The Dolmen de Soto is open to visitors who want to experience this remarkable monument for themselves. The entrance is located on the western side of the mound, where a reconstructed portal provides access to the interior. The passage is about 21 meters long and narrows from 0.8 meters wide at the entrance to 3.1 meters wide at the chamber. The chamber is about 3.9 meters high and has a circular shape. The passage and the chamber are covered by 20 capstones that form the roof of the dolmen. The best time to visit is during the equinoxes, when the first rays of sunlight illuminate the interior of the dolmen for a few minutes, creating a spectacular effect.

Leave a Reply