Scientists have verified the first occurrences of leprosy in wild chimpanzees, a bacterial illness that usually affects humans. Although it’s unclear how the chimps contracted the virus, experts believe the findings indicate that leprosy is considerably more prevalent in chimps and other wild animals than previously thought.

The findings were published in the journal Nature by a multinational team of researchers from West Africa, Europe, and the United States. The findings were initially released as a preprint in November 2020, which was covered by IFLScience, but they have subsequently been peer reviewed and confirmed.

The leprosy cases were discovered in two wild populations of western chimps (Pan troglodytes verus) in Guinea-Cantanhez Bissau’s National Park and Côte d’Ivoire’s Ta National Park, separated by 1,000 kilometers (621 miles).

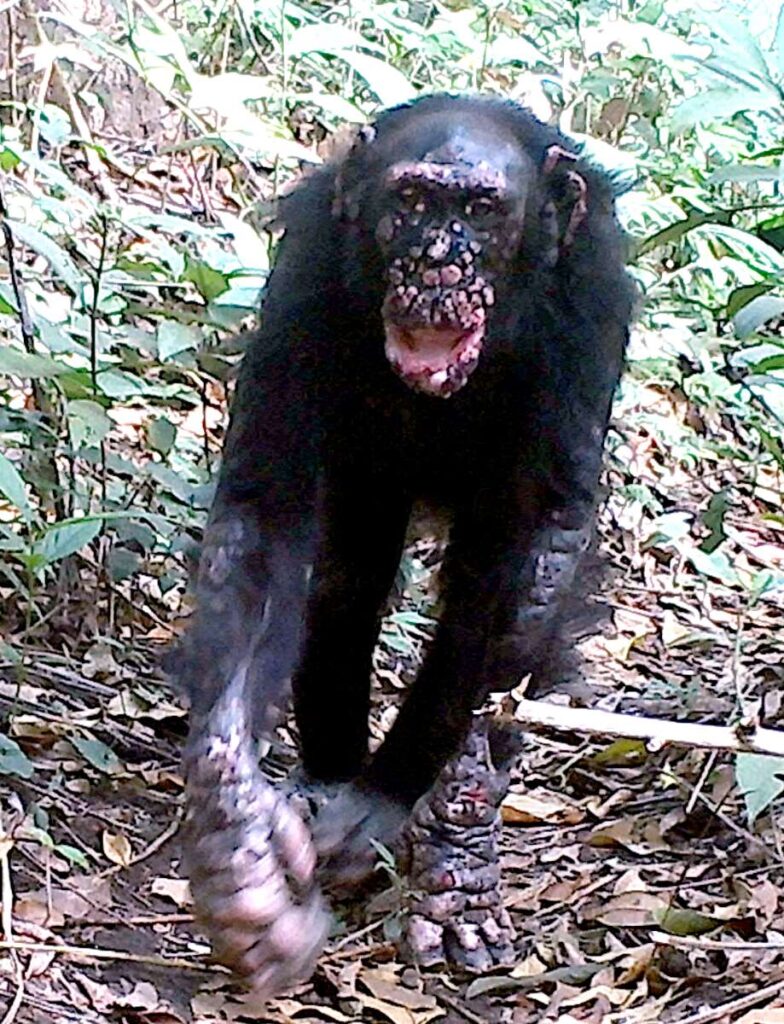

The outbreaks were first discovered thanks to hidden camera traps placed throughout the Cantanhez National Park, which revealed that at least four wild chimps had developed unusual lesions on their faces, ears, hands, and feet, as well as hair loss and a loss of pigment in their faces, symptoms that were strikingly similar to those seen in humans with leprosy. Similar symptoms were eventually discovered in chimps from a completely different group at the Ta National Park in Côte d’Ivoire.

Surprised by these findings, experts used genetic research to corroborate their assumptions. The researchers took stool samples and found Mycobacterium leprae, the germ that causes leprosy. The germs were also discovered in a necropsy sample collected from an adult female called Zora who was killed by a leopard in Ta National Park in 2009.

The M. leprae bacteria recovered from the excrement samples were subjected to further genetic research, which yielded some intriguing results. To begin with, the two epidemics had two distinct strains, suggesting that they started independently. Second, the genotypes of the bacterial strain responsible for both outbreaks are highly uncommon in humans, implying that the outbreak did not begin with human interaction.

Previous incidences of leprosy in captive chimpanzees have been documented, but this is the first time the illness has been verified in wild chimp communities. Squirrels and armadillos are among the wild creatures that have been documented to be affected. All of this raises the question of how they contracted the sickness.

“There’s still a lot we don’t understand!” Dr Kim Hockings, main study author from the University of Exeter’s Centre for Ecology and Conservation, told IFLScience, “This is really unexpected considering how ancient this disease is and the decades that it has impacted people.”

Human contact with chimps is unusual in Cantanhez and Ta National Parks, according to Dr. Hockings. M. leprae is also assumed to be spread by humans with evident signs, however no instances of leprosy have been documented among researchers or local research assistants.

“Although a human source cannot be ruled out,” Dr. Hockings stated, “poor human interaction combined with the rarity of the M. leprae genotype discovered in TNP [Ta National Park] chimpanzees among human groups in West Africa implies that recent human-to-chimp transmission is improbable.”

The researchers believe the chimps were more likely to come into touch with the germs through their mammalian prey. Alternatively, because M. leprae can live in soil and certain other mycobacteria can survive in water, it’s plausible that the chimps contracted the illness in their natural habitat.

It’s also unclear how chimps will be affected in the long run by this sickness. This is partially due to the fact that leprosy is a slow-moving illness that takes a long time to manifest in its patient. In Cantanhez, for example, a female chimpanzee showed early signs of leprosy in 2013, yet she is still alive and part of her chimp group.

Nonetheless, Western chimps are facing extinction owing to a variety of human-caused challenges, and the last thing they need is another sickness to worry about.

Dr. Hockings stated, “This is only one of the numerous stressors that wild chimps and other species are presently experiencing.”

“It’s plausible that people who are stressed are more prone to get leprosy, whether from human and environmental stresses in their natural surroundings or through intrusive treatments in biomedical institutions, for example.” My future studies will go further into this.”