The town of Grammichele is situated on the Italian island of Sicily, in the province of Catania. One of the few towns in the entire world with a distinctive hexagonal layout is this one.

After the great Sicilian earthquake of 1693 destroyed an earlier settlement called Occhialà, which was situated to the north of present-day Grammichele, the town was established. In the hope that St. Michele would shield the new town from further catastrophes, the survivors built a new settlement and gave it the name Grammichele in his honor.

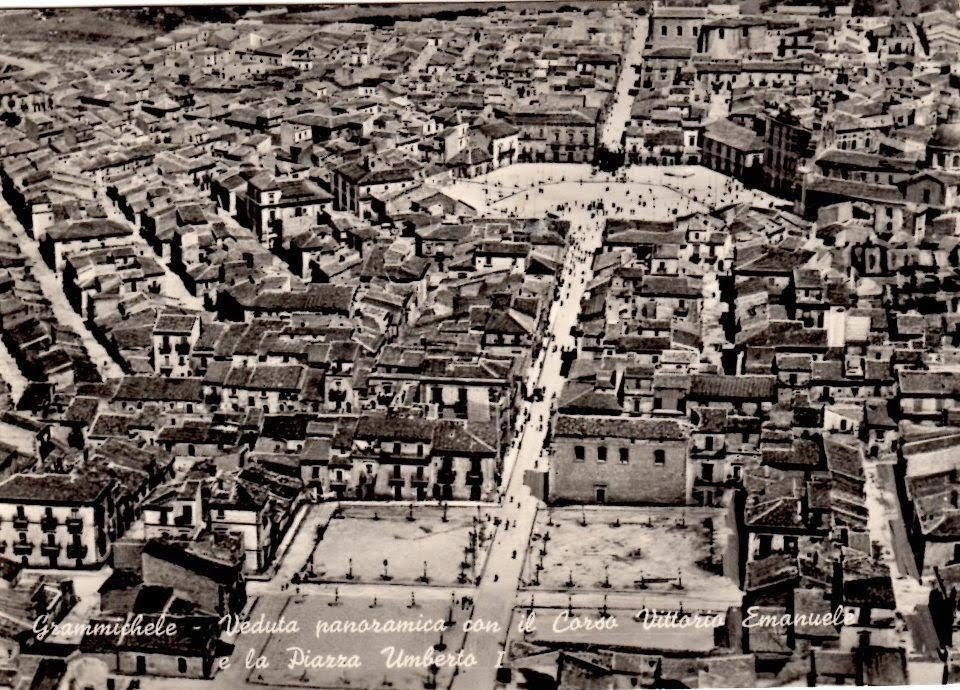

Carlo Maria Carafa Branciforte, the Prince of Roccella and Butera, constructed Grammichele. It was the first city in Europe with a hexagonal plan, and it was created by Michele da Ferla. Its design was most likely influenced by Palmanova, a fortified town constructed a century earlier. The primary distinction is that Grammichele has a hexagonal plan with the potential to be extended indefinitely, whereas Palmanova is based on a nine-sided polygon. Six roads converge on the main square, which is also hexagonal and where public offices are located, to form six sectors within the hexagonal plan created for Grammichele.

For residents to congregate in the event of a disaster, the town established numerous gathering spots. Around the primary hexagonal square, now known as Prince Carafa Square, a geometrically concentric road network connected these squares, which were all equally spaced apart. Four rectangular districts were planned beyond the hexagon. The Prince Palace was supposed to be in one of them, but it was never constructed.

According to authors Eran Ben-Joseph and David Gordon in a paper on hexagonal planning, hexagonal planning is uncommon today, “a mere oddity among a vast array of ideologies, theories, and methods.” Early in the 20th century, it briefly attracted the attention of a number of planners, engineers, and architects, but none were able to create detailed plans of this layout.

Charles Lamb, an art historian and architect from New York, promoted the hexagonal city plan as a useful and beautiful remedy for the problems of the contemporary city. He asserted that such a system would enable planned growth and healthy living in addition to the construction of lovely boulevards in the European style. The hexagonal design could potentially reduce the length of the water lines and those for the sewer system, according to Australian engineer Rudolf Mueller.

A greater number of buildings could be served by fewer hydrants and water mains, and shorter service lines could be installed between the mains and the buildings. Others, like Arthur Comey, pictured entire regions covered with tiny hexagonal towns connected to larger ones and to larger ones, and larger towns connected to significant metropolitan areas, forming a carpet of hexagonal cells.

Hexagonal planning, however, was abandoned during World War 2. Hexagonal blocks weren’t a practical solution because they were too unusual in real life. How would homes be numbered or streets named in a hexagonal layout? Eran Ben-Joseph questioned, “How would strangers navigate the streets of Hexagonopolis. In addition, triangular lots and awkward corners were disliked by residential developers and home buyers.

He says that while hexagonal planning may make sense in theory, it doesn’t always work in reality.

The main square of the Sicilian town of Grammichele with town hall, mother church and sundial. Photo credit: imagesef / Shutterstock.com

Leave a Reply