The amazing adaptability of plants to their environment is truly awe-inspiring, and nowhere is this more evident than in the leaf structure of xerophytic grasses like Ammophila arenaria, commonly known as marram grass. This hardy grass is a familiar sight on the sandy beaches and dunes of the UK coastline, where it plays a vital role in stabilising the shifting sands and creating a unique habitat for a wide range of wildlife.

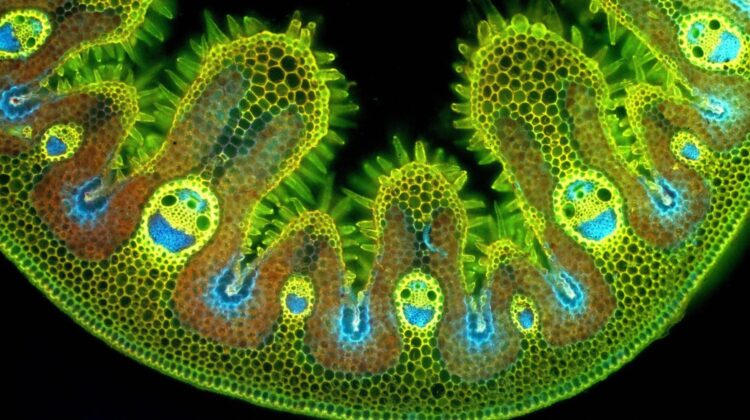

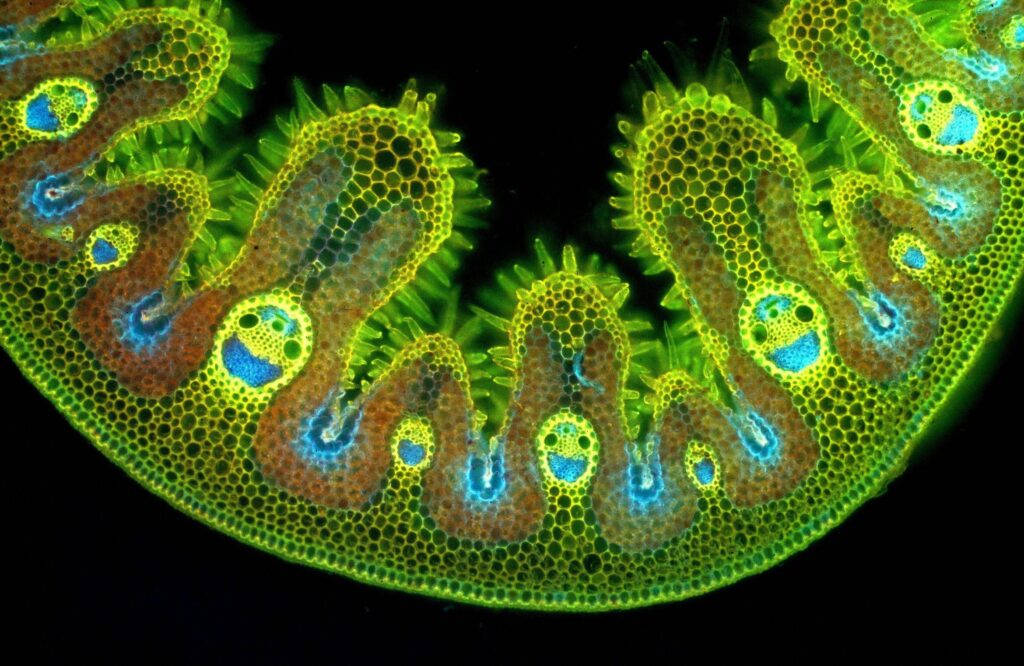

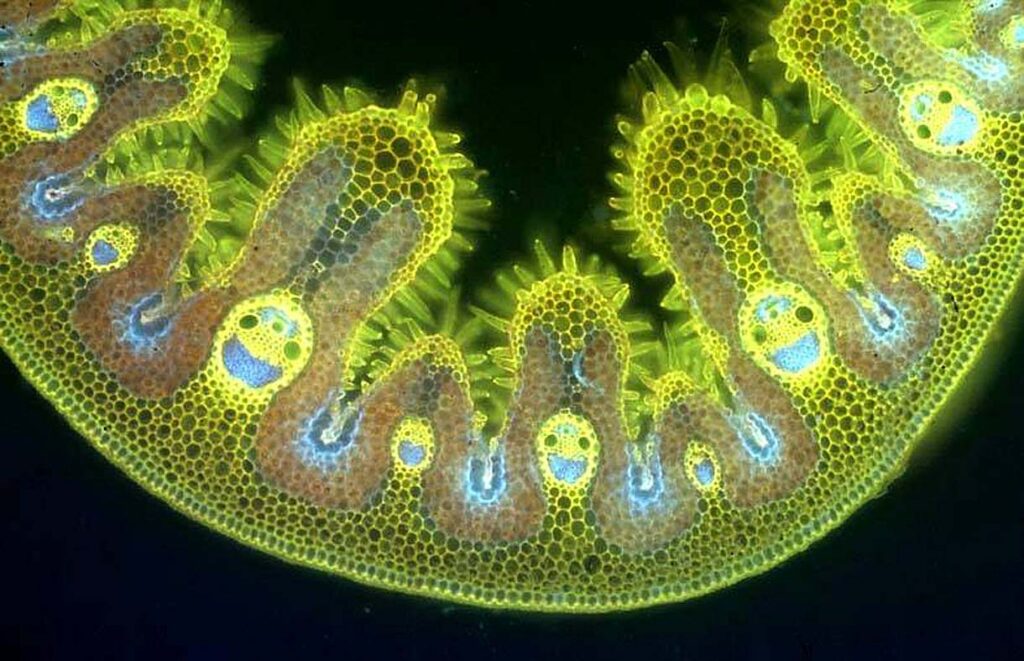

Recently, the biologist Phil Gates observed a transverse section of a marram grass leaf under the microscope, and was struck by the curious resemblance of the vascular bundles to smiling faces. This cross section reveals a wealth of information about the structure and function of the leaf, and how it enables the plant to survive in the harsh desert-like conditions of a sand dune.

The first thing that stands out in this cross section is the convoluted inner surface of the leaf, which is composed of ridges and furrows that run along the whole length of the leaf. These ridges and furrows serve to maximise the surface area of the leaf, allowing it to absorb as much sunlight as possible for photosynthesis. However, they also create a problem for the plant, as they increase the risk of water loss through transpiration.

To solve this problem, marram grass has evolved a clever mechanism for conserving water during periods of drought. By rolling up its leaves, the plant is able to minimise the exposed surface area of the leaf, and thus reduce the rate of water loss through transpiration. The clusters of thin-walled blue cells at the base of the furrows are responsible for unrolling the leaf when it rains, allowing the plant to take up water and resume normal growth.

The outer surface of the leaf is also highly adapted to the desert-like environment of the sand dune. It is composed of a layer of thick-walled cells, covered with a thick cuticle that resists wind-blown sand abrasion. This layer also acts like a spring, giving the leaf a natural tendency to roll up under drought conditions.

But perhaps the most intriguing feature of this cross section is the “smiling faces” of the leaf veins. These veins, which conduct water and sugars along the leaf, are like the plant’s internal plumbing system. They are arranged in snaking rows of reddish cells, which contain most of the chlorophyll and carry out photosynthesis. In order to make the dyes fluoresce, Gates had to irradiate the leaf section with blue-violet light, which paradoxically makes green chlorophyll fluoresce red.

All in all, this transverse section of a marram grass leaf is a fascinating glimpse into the complex and sophisticated mechanisms that plants have evolved to survive in some of the harshest environments on earth. It is a testament to the ingenuity of nature, and a reminder of the astonishing diversity of life on our planet.

Leave a Reply