Hidden beneath the dense foliage of Guatemala’s Petén rainforest lies an ancient city untouched by human hands for over a millennium. In its prime, this city thrived as the bustling heart of a vast Mesoamerican empire, home to millions of people who constructed an intricate and sprawling civilization. Now, in a groundbreaking archaeological feat, a team of international researchers has unveiled and meticulously mapped tens of thousands of these ancient structures. This extraordinary discovery was made possible through the application of airborne Light Detection and Ranging technology, or LiDAR, covering an astonishing 2,100 square kilometers (810 square miles) of the country’s lowlands.

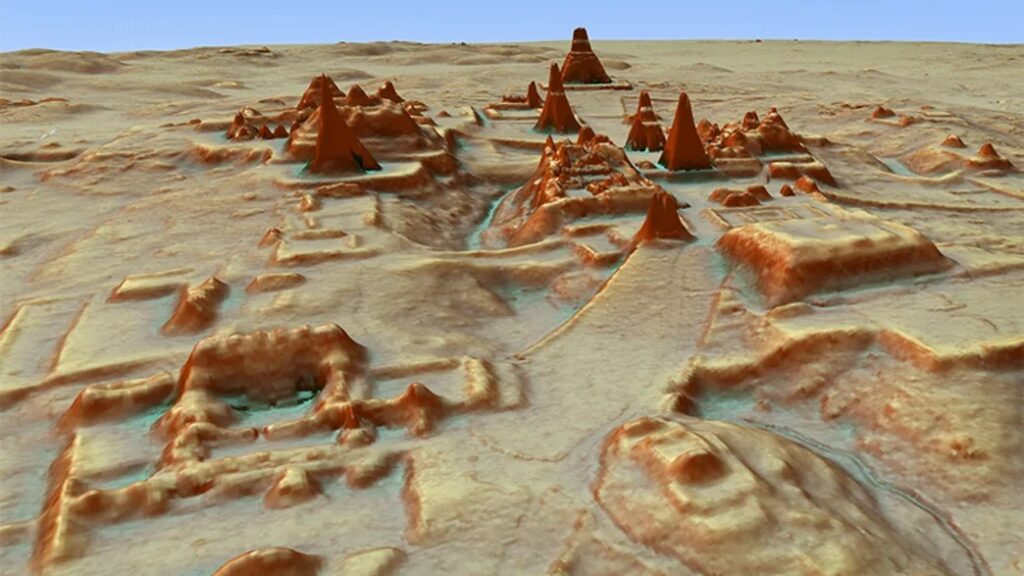

The introduction of LiDAR to this region dates back to 2009, initially focusing on the immediate vicinity of individual archaeological sites. However, it wasn’t until February, as reported by National Geographic, that archaeologists, led by the Guatemalan nonprofit organization, the PACUNAM Foundation, stumbled upon this colossal metropolis. Their findings were eventually published in the prestigious journal Science, more than six months after the initial discovery. Their groundbreaking revelation confirms the existence of an astounding 61,000 ancient structures, comprising houses, grand palaces, ceremonial complexes, and towering pyramids.

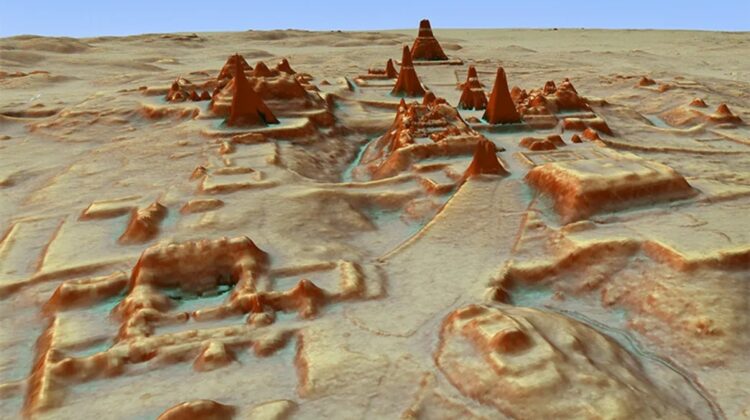

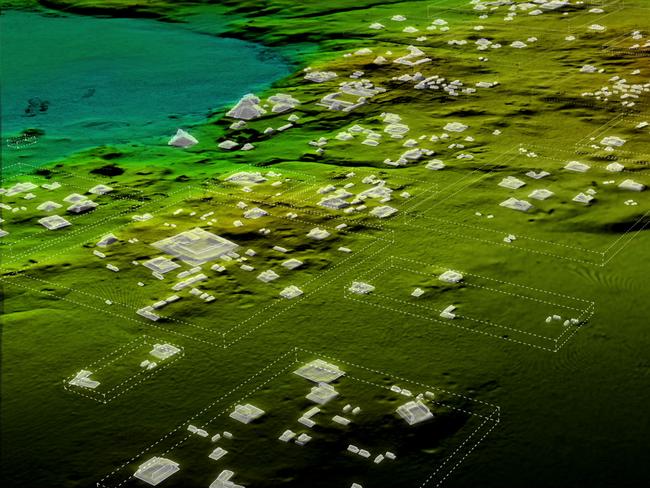

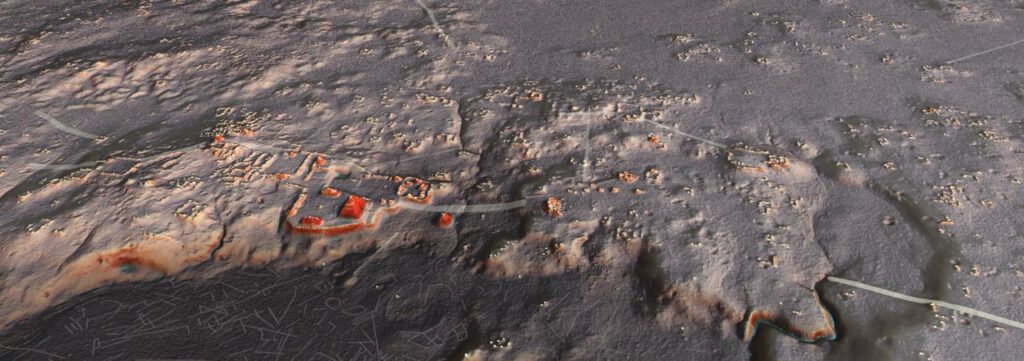

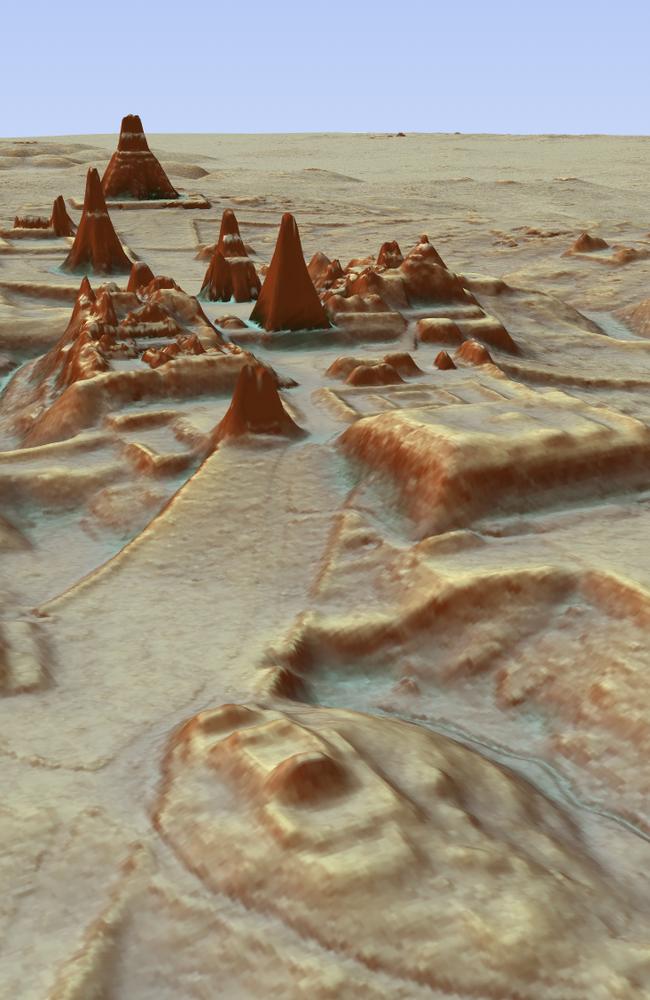

LiDAR’s remarkable ability to penetrate the thick rainforest canopy reveals subtle variations in elevation, enabling researchers to identify these topographical features as manmade structures, including walls, roads, and buildings, without ever setting foot on the jungle floor. Armed with this data, they can construct detailed three-dimensional maps in mere minutes, bypassing the years of painstaking fieldwork that traditional archaeological exploration demands.

One of the team members, Francisco Estrada-Belli, explained, “Seen as a whole, terraces and irrigation channels, reservoirs, fortifications, and causeways reveal an astonishing amount of land modification done by the Maya over their entire landscape on a scale previously unimaginable.”

In total, more than 61,000 ancient structures have been meticulously accounted for within the surveyed region. This suggests that during the Late Classic period (650-800 CE), the city was home to an estimated population of 7 to 11 million people. To put this in perspective, New York City, today, houses approximately 8.5 million residents. These ancient Mayan populations were not evenly distributed; varying degrees of urbanization characterized different regions across the vast expanse of 2,100 square kilometers (810 square miles). This extensive land modification was necessary to support the intensive agricultural practices required to sustain such a colossal population over centuries.

Marcello A. Canuto, a Maya archaeologist, reflected on the findings, stating, “It seems clear now that the ancient Maya transformed their landscape on a grand scale in order to render it more agriculturally productive. As a result, it seems likely that this region was much more densely populated than what we have traditionally thought.”

Furthermore, the international research team documented extensive causeways and intricate networks connecting the various urban centers. These findings underscore the remarkable level of interconnectivity among these disparate city centers and the substantial investment made in defensive systems, presumably to guard against the possibility of warfare.

As with any groundbreaking discovery, the authors conclude that their findings not only unlock new mysteries but also refine the focus of future fieldwork. They inspire regional studies across these continuous landscapes and mark the beginning of a bold era of research and exploration in the field of Maya archaeology. The jungle-penetrating lasers have unveiled a long-lost civilization’s secrets, shedding light on the sophistication and grandeur of the ancient Maya empire.

Leave a Reply