It’s not often in this line of work you receive a press release titled “All-purpose dinosaur opening,” but a particularly well-preserved Psittacosaurus specimen has, for the first time, been formally recognized as having the multi-faceted butt orifice known as a cloaca. The discovery, made by researchers from the University of Bristol, UK, was published in the journal Current Biology.

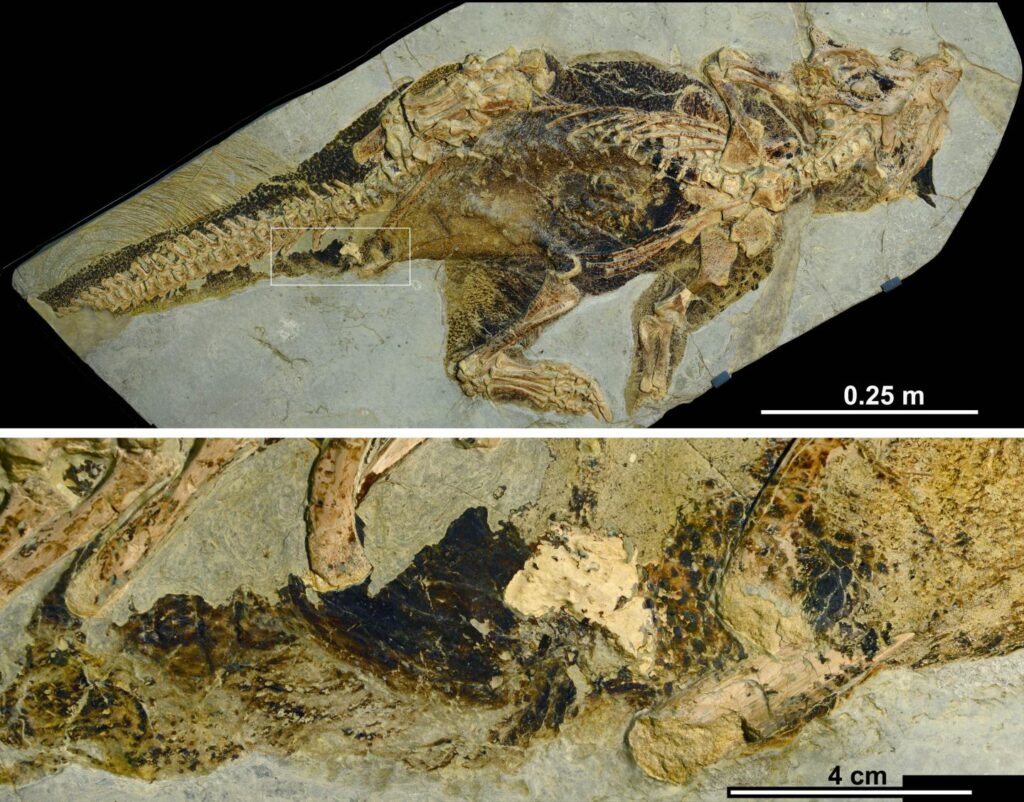

The 120-million-year-old specimen was discovered in northwestern China and is currently on display at the Senckenberg Museum of Natural History in Frankfurt, Germany. Psittacosaurus were herbivores related to Triceratops, and this especially well-preserved specimen has been the subject of extensive research into primitive feathers and the coloration of these dinosaurs.

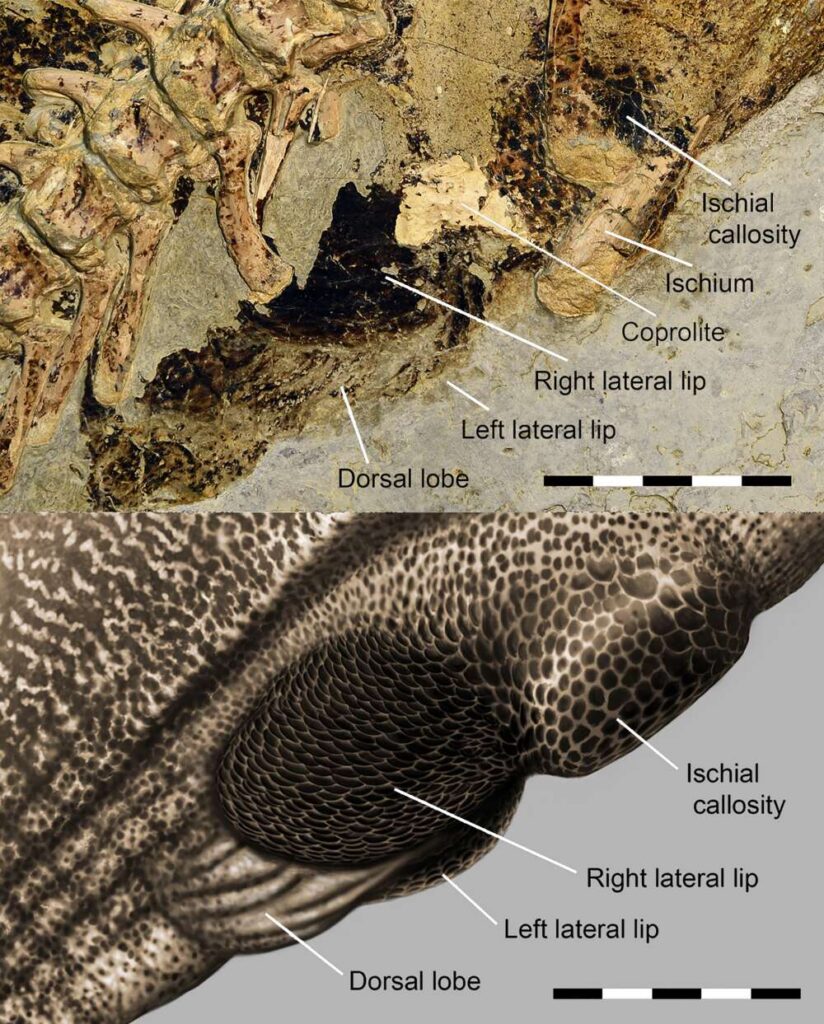

This is the first time, however, that the specimen has gained attention for its genital opening. Remarkably, this soft tissue structure is still visible on the fossil and appears as a black ridged area beneath the tail. Researchers note that there aren’t enough sexually dimorphic features on the non-avialan dinosaur to determine its sex, but the cloaca’s structure is similar to that of extant crocodilians, offering insights into its function and even how these dinosaurs likely mated.

“Indeed, they are pretty non-descript. We found the vent does look different in many different groups of tetrapods, but in most cases, it doesn’t tell you much about an animal’s sex,” said vertebrate penis and copulatory systems expert Dr. Diane Kelly from the University of Massachusetts Amherst, in a statement. “Those distinguishing features are tucked inside the cloaca, and unfortunately, they’re not preserved in this fossil.”

Some crocodilians have musky scent glands located near their genitals, which the researchers suspect may be visible in the Psittacosaurus specimen as two large, pigmented lobes on either side of the cloaca. Pigmentation with melanin is also a feature seen in the genitals of extant baboons and breeding salamanders, species known to use their private parts for displaying and signaling to potential mates. Researchers speculate that in its heyday, the cloaca of Psittacosaurus may have played a role in the herbivore’s pursuit of a partner.

“With only one cloaca from any extinct dinosaur, we can compare it to modern crocodiles and the only living dinosaurs, which are the birds,” Dr. Jakob Vinther from the University of Bristol’s School of Earth Sciences told IFLScience. “It looks a little like a crocodile cloaca, but it is unique in many ways. We can see that the cloaca was visually striking with melanin pigment and hence it may have flashed its back end during courtship. It may also have harbored a set of glands that produced an irresistible smell – to other psittacosaurs, that is. We see those in living crocodiles, and the anatomy of the dinosaur cloaca may well have been suited for such internal glands also.”

A cloaca is a wondrous thing. Seen in animals alive today, including birds, reptiles, amphibians, some fish, and monotremes, this one-size-fits-all genital structure facilitates the passage of digestive, reproductive, and urinary matter. Is it a gross oversimplification of the complex excretory needs of living beings or a convenient alternative to managing the messier aspects of being alive? The jury’s still out.

So what’s next for the world-first discovery? “Since this is the first and only cloaca ever described, we just have to sit tight until the next fortuitous fossil appears,” said Vinther. “That may not be for another 100 years, though.”

Leave a Reply