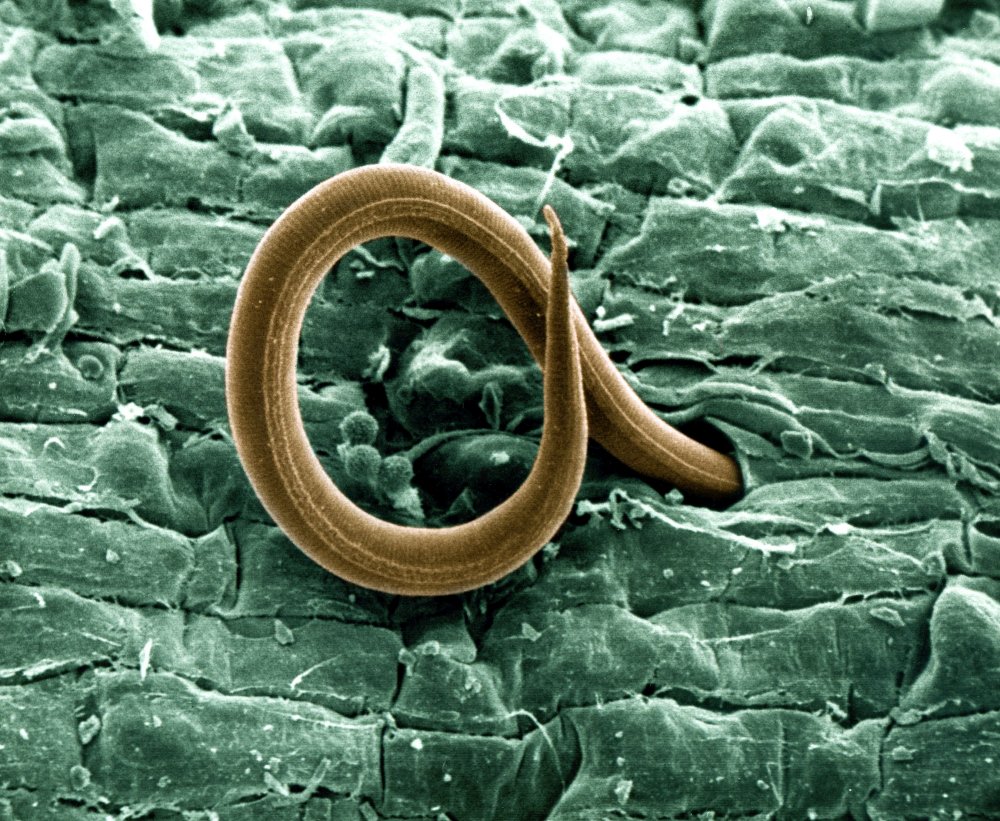

Researchers discovered live nematodes after collecting and thawing samples of permafrost material that had been frozen for 42,000 years (roundworms).

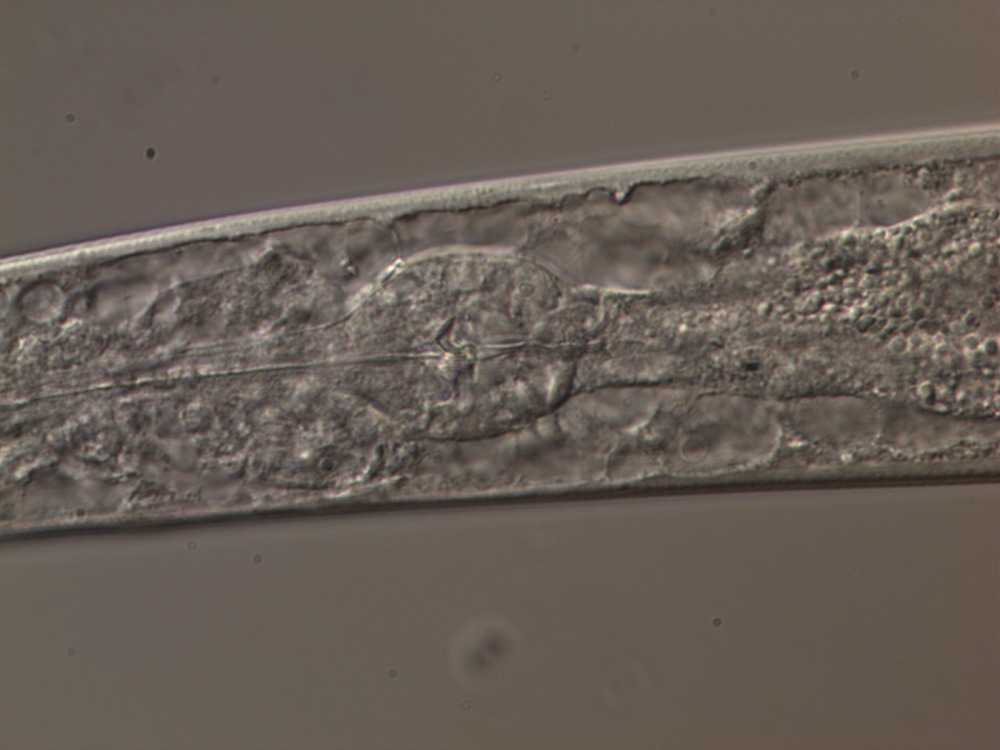

More than 300 frozen soil samples of various ages and places were dug out from the permafrost around the Arctic by a group of Russian biologists and brought back to their lab in Moscow for further examination. They then isolated two worms on Petri plates using a nutrient mixture at 20 degrees Celsius, in partnership with Princeton University (68 Fahrenheit). The roundworms began to move and feed after only a few weeks, according to Science Alert.

This is the new world record for the length of time an animal may be kept in cryogenic storage. Apart from exposing new endurance limitations, the discovery may also be advantageous in terms of conserving our own tissues. Doklady Biological Sciences reported the findings.

The two female worms were identified as Panagrolaimus detritophagus and Plectus parvus, respectively. The former was discovered 30 meters (100 feet) below in a ground squirrel burrow that had fallen in and froze about 32,000 years ago. The latter was obtained from a 3.5-metre-deep bore sample (about 11.5 feet). Carbon dating was utilized to assess the age of the sample, which was found to be around 42,000 years old.

Even the researchers concede that contamination cannot be completely ruled out. They do stress, however, that they followed stringent sterility standards, and that contamination of the samples was improbable because they originated from a syncryogenic permafrost, which means that freezing and sediment buildup occurs at the same time.

Furthermore, modern worms aren’t known for digging that far into permafrost, and seasonal thawing is restricted to about 80 cm (under 3 feet). When the region was at its hottest, roughly 9000 years ago, there was no sign of melting beyond 1.5 meters (5 feet).

All of this implies that we may be reasonably certain that these worms did indeed rise from their extraordinarily extended slumber.

They not only awoke, but they also cloned some additional family members! The researchers then cultivated these cloned worms independently, and they, too, flourished.

Nematodes, or roundworms, and their near relative, the tardigrade, have been known to tolerate exceedingly harsh environmental circumstances (tardigrades have been shown to survive even the vacuum of space). Some roundworms have been resurrected after being inactive for 30 to 39 years, but nothing on this magnitude has ever been seen before.

The discovery of organisms that can remain dormant for tens of thousands of years is a remarkable achievement. Over millennia, learning more about their molecular processes for limiting ice damage and resisting the ravages of oxidation on DNA might pave the path for improved cryopreservation technology.

The researchers wrote in their paper, “It is evident that this capacity shows that Pleistocene nematodes have certain adaptation processes that may be of scientific and practical value for allied disciplines of science, such as cryomedicine, cryobiology, and astrobiology.”

Unfortunately, the discoveries also have a darker aspect to them. Since the permafrost – the permanently frozen earth of northern regions – began to thaw as the Earth warmed, there have been fears that hazardous viruses trapped in deep freeze for millennia might be released. Although nematodes are unlikely to represent a significant threat, their persistence shows that a wide range of creatures — from bacteria to mammals, plants to fungus – might make a comeback after a lengthy absence.

And we can only speculate on what it might entail for the ecosystems around us, and for us inside them.

In Siberia’s vanishing iceland, we can only hope that a few sleepy worms are all we have to worry about.